Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protection" under the law to all people. Under the doctrine, as long as the facilities provided to each "race" were equal, state and local governments could require that services, facilities, public accommodations, housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation be segregated by "race", which was already the case throughout the states of the former Confederacy. The phrase was derived from a Louisiana law of 1890, although the law actually used the phrase "equal but separate".

Charles Hamilton Houston was a prominent African-American lawyer, Dean of Howard University Law School, and NAACP first special counsel, or Litigation Director. A graduate of Amherst College and Harvard Law School, Houston played a significant role in dismantling Jim Crow laws, especially attacking segregation in schools and racial housing covenants. He earned the title "The Man Who Killed Jim Crow".

Briggs v. Elliott, 342 U.S. 350 (1952), on appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, challenged school segregation in Summerton, South Carolina. It was the first of the five cases combined into Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the famous case in which the U.S. Supreme Court declared racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional by violating the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause. Following the Brown decision, the district court issued a decree that struck down the school segregation law in South Carolina as unconstitutional and required the state's schools to integrate. Harry and Eliza Briggs, Reverend Joseph A. DeLaine, and Levi Pearson were awarded Congressional Gold Medals posthumously in 2003.

Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park was established in Topeka, Kansas, on October 26, 1992, by the United States Congress to commemorate the landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the case Brown v. Board of Education aimed at ending racial segregation in public schools. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously declared that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal" and, as such, violated the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees all citizens "equal protection of the laws."

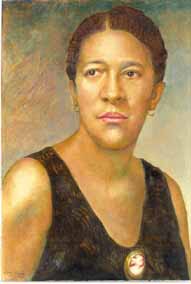

Modjeska Monteith Simkins was an important leader of African-American public health reform, social reform and the Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina.

Mary Church Terrell was one of the first African-American women to earn a college degree, and became known as a national activist for civil rights and suffrage. She taught in the Latin Department at the M Street School —the first African American public high school in the nation—in Washington, DC. In 1895, she was the first African-American woman in the United States to be appointed to the school board of a major city, serving in the District of Columbia until 1906. Terrell was a charter member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1909) and the Colored Women's League of Washington (1892). She helped found the National Association of Colored Women (1896) and served as its first national president, and she was a founding member of the National Association of College Women (1923).

The civil rights movement (1896–1954) was a long, primarily nonviolent action to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans. The era has had a lasting impact on American society – in its tactics, the increased social and legal acceptance of civil rights, and in its exposure of the prevalence and cost of racism.

This is a timeline of African-American history, the part of history that deals with African Americans.

Segregation academies are private schools in the Southern United States that were founded in the mid-20th century by white parents to avoid having their children attend desegregated public schools. They were founded between 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregated public schools were unconstitutional, and 1976, when the court ruled similarly about private schools.

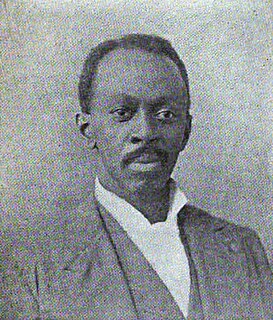

Archibald Henry Grimké was an American lawyer, intellectual, journalist, diplomat and community leader in the 19th and early 20th centuries. He graduated from freedmen's schools, Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and Harvard Law School and served as American Consul to the Dominican Republic from 1894 to 1898. He was an activist for rights for blacks, working in Boston and Washington, D.C. He was a national vice-president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as president of its Washington, D.C. branch.

Richard Robert Wright Sr. was an American military officer, educator and college president, politician, civil rights advocate and banking entrepreneur. Among his many accomplishments, he founded a high school, a college, and a bank. He also founded the National Freedom Day Association in 1941.

Paul Laurence Dunbar High School is a public secondary school located in Washington, D.C. The school was America's first public high school for black students.

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the South had adopted laws, beginning in the late 19th century, banning discrimination in public accommodations and voting. Southern laws were enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by white Southern Democrat–dominated state legislatures to disenfranchise and remove political and economic gains made by African Americans during the Reconstruction period. Jim Crow laws were enforced until 1965.

Black schools, also referred to as "colored" schools, were racially segregated schools in the United States that originated after the American Civil War and Reconstruction era. The phenomenon began in the late 1860s during Reconstruction era when Southern states under biracial Republican governments created public schools for the ex enslaved. They were typically segregated. After 1877, conservative whites took control across the South. They continued the black schools, but at a much lower funding rate than white schools.

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington, Moorfield Storey and Ida B. Wells. Leaders of the organization included Thurgood Marshall and Roy Wilkins.

Garnet Crummell Wilkinson was an American educator best known for running the African-American public school system in Washington, DC during segregation. During this time Washington, DC had the reputation of having the best public schools in the nation for African Americans. Wilkinson enjoyed a nearly 50-year career in Washington's public schools and served as assistant superintendent for 30 years. He also favored "separate, but equal" schooling.

The American Teachers Association (1937-1966), formerly National Colored Teachers Association (1906–1907) and National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools (1907–1937), was a professional association and teachers' union representing teachers in schools in the South for African Americans during the period of legal racial segregation in United States. In 1954 the United States Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended legal segregation.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

The Palmetto State Teachers Association( PSTA) is the largest professional organization for educators in the U.S. state of South Carolina. PSTA was founded in 1976 as a non-profit organization and currently has 12,500 member teachers.