Related Research Articles

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, was a secret revolutionary society founded in the Ottoman territories in Europe, that operated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Georgi Nikolov Delchev, known as Gotse Delchev or Goce Delčev, was an important Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary (komitadji), active in the Ottoman-ruled Macedonia and Adrianople regions at the turn of the 20th century. He was the most prominent leader of what is known today as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), a secret revolutionary society that was active in Ottoman territories in the Balkans at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. Delchev was its representative in Sofia, the capital of the Principality of Bulgaria. As such, he was also a member of the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC), participating in the work of its governing body. He was killed in a skirmish with an Ottoman unit on the eve of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising.

Krste Petkov Misirkov was a philologist, journalist, historian and ethnographer from the region of Macedonia.

Hristo Tatarchev was a Macedonian Bulgarian doctor, revolutionary and one of the founders of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). Tatarchev authored several political journalistic works between the First and Second World War. He is considered an ethnic Macedonian in the Macedonian historiography.

Todor Aleksandrov Poporushov, best known as Todor Alexandrov, also spelt as Alexandroff, was a Bulgarian revolutionary, army officer, politician and teacher, who fought for the freedom of Macedonia as a second Bulgarian state on the Balkans. He was a member of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organisation (IMARO) and later of the Central Committee of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO).

Voydan Popgeorgiev – Chernodrinski was a Bulgarian playwright from the region of Macedonia. His pseudonym is derived from the river Black Drin. Today he is considered an ethnic Macedonian writer in North Macedonia and a figure who laid the foundations of the Macedonian theatre and the dramatic arts.

Mara Buneva was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary, member of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. She is famous for the assassination of the former Serbian Chetnik commander and Yugoslav legal official of the Skopje Oblast Velimir Prelić, after which she committed suicide. Today Buneva is considered as a heroine in Bulgaria, while in Serbia and North Macedonia she is regarded as a controversial Bulgarophile.

Bulgarians are an ethnic minority in North Macedonia. Bulgarians are mostly found in the Strumica area, but over the years, the absolute majority of southeastern North Macedonia have declared themselves Macedonian. The town of Strumica and its surrounding area were part of the Kingdom of Bulgaria between the Balkan wars and the end of World War I, as well as during World War II. The total number of Bulgarians counted in the 2021 Census was 3,504 or roughly 0.2%. Around 98,000 nationals of North Macedonia have received Bulgarian citizenship since 2001 and some 53,000 are still waiting for such, almost all based on declared Bulgarian origin. In the period when North Macedonia was part of Yugoslavia, there was also migration of Bulgarians from the so called Western Outlands in Serbia.

Mihailo Apostolski was a Macedonian general, partisan, military theoretician, politician, academic and historian. He was the commander of the General Staff of the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Macedonia, colonel general of the Yugoslav National Army, and was declared a People's Hero of Yugoslavia.

World War II in Yugoslav Macedonia started with the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941. Under the pressure of the Yugoslav Partisan movement, part of the Macedonian communists began in October 1941 a political and military campaign to resist the occupation of Vardar Macedonia. Officially, the area was called then Vardar Banovina, because the very name Macedonia was prohibited in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. It was occupied mostly by Bulgarian, but also by German, Italian, and Albanian forces.

The Brsjak revolt broke out on 14 October 1880 in the Poreče region of the Monastir Vilayet, led by rebels who sought the liberation of Macedonia from the Ottoman Empire. According to Ottoman sources the goal of the revolt was the accession of Macedonia to Bulgaria. The rebels received secret aid from Principality of Serbia, which had earlier been at war with the Ottoman Empire, until Ottoman and Russian diplomatic intervention in 1881. The Ottoman Gendarmerie succeeded in suppressing the rebellion after a year.

The Kostur dialect, is a member of the Southwestern subgroup of the Southeastern group of dialects of the Macedonian language. This dialect is mainly spoken in and around the town of Kastoria, known locally in Macedonian as Kostur, and in the surrounding Korešta region, which encompasses most of the area to the northwest of the town. The Kostur dialect is also partially spoken in Albania, most notably in Bilisht and the village of Vërnik (Vrabnik). The dialect is partially preserved among the ″people of Bulgarian origin in Mustafapaşa and Cemilköy, Turkey, descending from the village of Agios Antonios (Zhèrveni) in Kostur region ″.

Bulgaria–North Macedonia relations are the bilateral relations between the Republic of Bulgaria and the Republic of North Macedonia. Both countries are members of the Council of Europe, and NATO. Bulgaria is a member of the European Union. Bulgaria was the first country to recognize the independence of its neighbour in 1992. Both states signed a friendship treaty in 2017. North Macedonia has been attempting to join the EU since 2004, while EU governments officially gave their permissions to enter accession talks in March 2020. Nevertheless, North Macedonia and Bulgaria have complicated neighborly relations, thus the Bulgarian factor is known in Macedonian politics as "B-complex".

Pretor is a village in the Resen Municipality of North Macedonia, on the northeastern shore of Lake Prespa. It is over 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) south of the municipal centre of Resen.

The Stracin–Kumanovo operation was an offensive operation conducted in 1944 by the Bulgarian Army against German forces in occupied Yugoslavia which culminated in the capture of Skopje in 1944. With the Bulgarian declaration of war on Germany on September 8, followed by Bulgarian withdrawal from the area, the German 1st Mountain Division moved north, occupied Skopje, and secured the strategic Belgrade–Nis–Salonika railroad line. On October 14, withdrawing from Greece, Army Group E faced Soviet and Bulgarian divisions advancing in Eastern Serbia and Vardar Macedonia; by November 2, the last German units left Northern Greece.

Nikola Kirov was a Bulgarian teacher, revolutionary and public figure, a member of IMRO.

Day of the Macedonian Uprising is a public holiday in North Macedonia, commemorating what is considered there the beginning of the communist resistance against fascism during World War II in Yugoslav Macedonia, on October 11.

Naum Hristov Tomalevski was a Bulgarian revolutionary, participant in the Macedonian revolutionary movement, member of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).

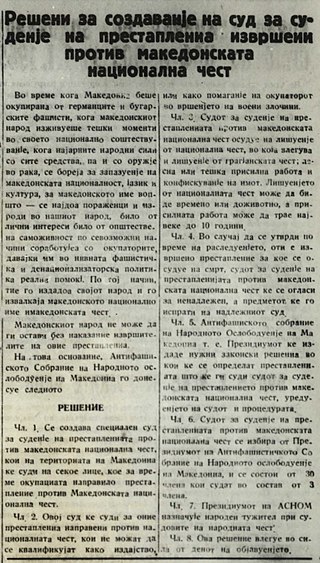

The Law for the Protection of Macedonian National Honour was a statute passed by the government of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia at the end of 1944. The Presidium of Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) established a special court for the implementation of this law, which came into effect on January 3, 1945. This decision was taken at the second session of this assembly on 28–31 December 1944.

Petar Traykov Girovski was a Bulgarian Army officer, later activist of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. Afterwards he became close to some communist circles and after the Second World War participated in Yugoslav and Bulgarian politics.

References

- ↑ "Софија со сочувство за македонскиот Бугарин Панде Ефтимов" [Sofia with condolences for the Macedonian Bulgarian Pande Eftimov]. Expres.mk (in Macedonian). August 15, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ↑ "Падне Евтимов - великият българин" [Pande Evtimov - the Great Bulgarian]. Interview with Pande Evtimov, Radio Focus, 27 January 2011 (in Bulgarian). Паметта на българите, www.pamettanabulgarite.com. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- ↑ Максимовски, Илија (1991). 'According to his court trial official documents No.273/72 in 1972, Pande declared himself as Macedonian and one of the reasons for his imprisonment was agitating for unification of Vardar, Egej and Pirin into one independent Macedonian state.' Политичкиот затвореник во Македонија. Skopje: MRTV. p. 91.

- ↑ Ристески, Д-р. Стојан (1995). Судени за Македонија (1945-1985). Ohrid: Macedonia Prima-Ohrid. ISBN 9989-619-03-4.

- ↑ According to Eftimov, there is a fear of saying that you are a Bulgarian in Republic of Macedonia, but this should not be a reason for a person to stop fighting for his identity. Regarding the fact that many people are afraid to say it openly, there is a logical answer and it is that if you are a Bulgarian in Republic of Macedonia, you are a national traitor, there is no work for you, the whole state apparatus lurks you and in the moment you do something with the slightest violation, the state blackes your life. For more see: Панде Ефтимов: Нямаме държавници и политици с отговорност за Македония. FROG NEWS; 13.03.2014.

- ↑ Панде Ефтимов - един от най-големите радетели на българското в Македония почина в Горна България. в-к Земя, 15 Август 2017.

- ↑ "Панде Ефтимов, неформалният лидер на българите в Република Македония: Само с факти от българската история не ще преборим агресията на македонизма" [Pande Eftimov, the informal leader of the Bulgarians in the Republic of Macedonia: We will not overcome the aggression of Macedonianism only with facts from Bulgarian history]. Fakel.bg (in Bulgarian). March 4, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ↑ Николай Кочанков, От надежда към покруса: Западна Македония в българската външна политика (1941-1944); (2007) Херон Прес. София, ISBN 978-954-580-231-7.

- 1 2 3 Съболезнователен адрес по повод кончината на Панде Ефтимов. на външните работи на Република България, 13 август 2017.

- ↑ Krastev, Nikolay (July 20, 2015). "Панде Ефтимов: Българите в Македония са изолирани от политиците в страната ни" [Pande Eftimov: Bulgarians in Macedonia are isolated from politicians in our country]. BNR.bg (in Bulgarian). Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ↑ Петър Христов Петров (1994) Македония: история и политическа съдба, том 3, Изд-во "Знание" ООД, стр. 274, ISBN 954621129X.

- ↑ Костадин Филипов, Отново ще си спомним за Панде Ефтимов. БНТ1, 03.11.2018.