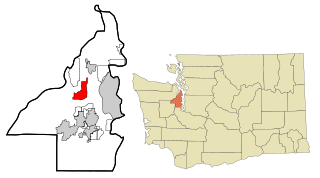

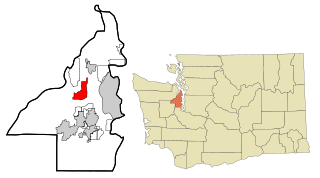

Silverdale is an unincorporated community in Kitsap County, Washington, in the United States. Despite many failed attempts at incorporation, Silverdale has not become a city. The population was 20,733 at the 2020 census. For statistical purposes, the United States Census Bureau has defined Silverdale as a census-designated place (CDP).

The Makah are an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast living in Washington, in the northwestern part of the continental United States. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Makah Indian Tribe of the Makah Indian Reservation, commonly known as the Makah Tribe.

The Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center is a Native American cultural center in Seattle, Washington, described by its parent organization United Indians of All Tribes as "an urban base for Native Americans in the Seattle area." Located on 20 acres in Seattle's Discovery Park in the Magnolia neighborhood, the center developed from activism by Bernie Whitebear and other Native Americans, who staged a generally successful self-styled "invasion" and occupation of the land in 1970. Most of the former Fort Lawton military base had been declared surplus by the U.S. Department of Defense. "The claim [Whitebear and others made] to Fort Lawton was based on rights under 1865 U.S.-Indian treaties promising reversion of surplus military lands to their original owners."

Wilma Pearl Mankiller was a Native American activist, social worker, community developer and the first woman elected to serve as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Born in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, she lived on her family's allotment in Adair County, Oklahoma, until the age of 11, when her family relocated to San Francisco as part of a federal government program to urbanize Indigenous Americans. After high school, she married a well-to-do Ecuadorian and raised two daughters. Inspired by the social and political movements of the 1960s, Mankiller became involved in the Occupation of Alcatraz and later participated in the land and compensation struggles with the Pit River Tribe. For five years in the early 1970s, she was employed as a social worker, focusing mainly on children's issues.

The Seattle metropolitan area is an urban conglomeration in the U.S. state of Washington that comprises Seattle, its surrounding satellites and suburbs. The United States Census Bureau defines the Seattle–Tacoma–Bellevue, WA metropolitan statistical area as the three most populous counties in the state: King, Pierce, and Snohomish. Seattle has the 15th largest metropolitan statistical area (MSA) in the United States with a population of 4,018,762 as of the 2020 census, over half of Washington's total population.

United Indians of All Tribes is a non-profit foundation that provides social and educational services to Native Americans in the Seattle metropolitan area and aims to promote the well being of the Native American community of the area. The organization is based at the Daybreak Star Cultural Center in Seattle, Washington's Discovery Park. UIATF has an annual budget of approximately $4.5 million as of 2013.

Hansville is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Kitsap County, Washington, United States. Its population was 3,858 as of the 2020 census. The coastal community is located at the northern end of the Kitsap Peninsula and is about 16 miles (26 km) northeast of Poulsbo, the nearest city.

Princess Angeline, also known in Lushootseed as Kikisoblu, Kick-is-om-lo, or Wewick, was the eldest daughter of Chief Seattle.

Lawney L. Reyes was an American Sin-Aikst artist, curator, and memoirist, based in Seattle, Washington.

Bernie Whitebear, birth name Bernard Reyes, was an American Indian activist in Seattle, Washington, a co-founder of the Seattle Indian Health Board (SIHB), the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation, and the Daybreak Star Cultural Center, established on 20 acres of land acquired for urban Indians in the city.

Catherine Herrold Troeh was an American historian, artist, activist and advocate for Native American rights and culture, especially in the Pacific Northwest. She was a member and elder of the Chinook tribe and a direct descendant of the great chief, or tyee, of the Chinook people, Comcomly.

Helmi Dagmar Juvonen was an American artist active in Seattle, Washington. Although she worked in a wide variety of media, she is best known for her prints, paintings, and drawings. She is associated with the artists of the Northwest School.

Alice Henson Ernst was an American playwright, professor and author. She conducted anthropological work among the Native Americans in Oregon. Ernst was also well-known for her history and research of pioneer theater in the northwest. Ernst taught English and drama at the University of Washington and the University of Oregon.

Sandra Sunrising Osawa is a Makah filmmaker and poet. She is best known for her films Lighting the Seventh Fire (1995) and On and Off the Res with Charlie Hill (1999).

The Ozette, also known locally as Makah Ozette or Anna Cheeka's Ozette is the oldest variety of potato grown in the Pacific Northwest region. This potato, of the petite heirloom fingerling type, was grown for over two centuries by the Makah tribe native to Washington and was "rediscovered" in the late 1980s.

Johnpaul Jones is an American architect and landscape architect, partner in Seattle-based architecture firm Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects, best known for innovative habitat immersion method design of zoo exhibits. A person who self-identifies as Native American, he has also executed many projects for various Native American organizations, and was lead design consultant for the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of the American Indian, completed 2004 in Washington, D.C. He was the first architect ever to receive the National Humanities Medal.

Ella Jean Hill Chaudhuri was an American community leader, activist, and author. She was a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, executive director of the Tucson Indian Center, and director of the Traditional Indian Alliance. She was inducted into the Arizona Women's Hall of Fame posthumously, in 2013.

Pearl Anderson Wanamaker was an American educator and politician. She served in the Washington State Legislature from 1928 to 1940. She was also Washington's Superintendent of Public Instruction from 1941 to 1957. She was president of the National Education Association.

Ella Pierre Aquino was a Lummi-Yakama-Puyallup civil rights activist and community organizer who was a matriarch of the Native American community in Seattle. She advocated on behalf of foster children and co-founded the American Indian Women's Service League in 1958. She published the Indian Center News and served as editor and columnist for the Northwest Indian News. Aquino was one of the key organizers of the occupation of Fort Lawton in 1970, which led to the establishment of the Daybreak Star Cultural Center in Discovery Park. She was the subject of the 1987 documentary Princess of the Pow Wow.