Related Research Articles

Palliser's Triangle, or the Palliser Triangle, is a semi-arid steppe occupying a substantial portion of the Western Canadian Canadian Prairies, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba, within the Great Plains region. While initially determined to be unsuitable for crops outside of the fertile belt due to arid conditions and dry climate, expansionists questioned this assessment, leading to homesteading in the Triangle. Agriculture in the region has since suffered from frequent droughts and other such hindrances.

The Chipewyan are a Dene Indigenous Canadian people of the Athabaskan language family, whose ancestors are identified with the Taltheilei Shale archaeological tradition. They are part of the Northern Athabascan group of peoples, and hail from what is now Western Canada.

Edgar Dewdney, was a Canadian surveyor, road builder, Indian commissioner and politician born in Devonshire, England. He emigrated to British Columbia in 1859 in order to act as surveyor for the Dewdney Trail that runs through the province. In 1870, Dewdney decided to take up a role in Canadian government. In this year, he was elected to the Legislative Council of British Columbia as a representative from the Kootenay region. In 1872, he was elected as a Member of the Parliament of Canada for the Yale region representing the Conservative party. He was reelected to this position in 1874 and again in 1878. Dewdney served as Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories from 1879 to 1888, and the fifth Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia from 1892 to 1897. Additionally, he served as the Indian commissioner in the North-West Territories from 1879 until 1888. In 1897, Dewdney retired from politics and began working as a financial agent until his death in 1916.

First Nations in Alberta are a group of people who live in the Canadian province of Alberta. The First Nations are peoples recognized as Indigenous peoples or Plains Indians in Canada excluding the Inuit and the Métis. According to the 2011 Census, a population of 116,670 Albertans self-identified as First Nations. Specifically there were 96,730 First Nations people with registered Indian Status and 19,945 First Nations people without registered Indian Status. Alberta has the third largest First Nations population among the provinces and territories. From this total population, 47.3% of the population lives on an Indian reserve and the other 52.7% live in urban centres. According to the 2011 Census, the First Nations population in Edmonton totalled at 31,780, which is the second highest for any city in Canada. The First Nations population in Calgary, in reference to the 2011 Census, totalled at 17,040. There are 45 First Nations or "bands" in Alberta, belonging to nine different ethnic groups or "tribes" based on their ancestral languages.

Treaty Five is a treaty between Queen Victoria and Saulteaux and Swampy Cree non-treaty band governments and peoples around Lake Winnipeg in the District of Keewatin. Much of what is today central and northern Manitoba was covered by the treaty, as were a few small adjoining portions of the present-day provinces of Saskatchewan and Ontario.

Treaty 6 is the sixth of the numbered treaties that were signed by the Canadian Crown and various First Nations between 1871 and 1877. It is one of a total of 11 numbered treaties signed between the Canadian Crown and First Nations. Specifically, Treaty 6 is an agreement between the Crown and the Plains and Woods Cree, Assiniboine, and other band governments at Fort Carlton and Fort Pitt. Key figures, representing the Crown, involved in the negotiations were Alexander Morris, Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba and The North-West Territories; James McKay, The Minister of Agriculture for Manitoba; and William J. Christie, a chief factor of the Hudson's Bay Company. Chief Mistawasis and Chief Ahtahkakoop represented the Carlton Cree.

Harold Cardinal was a Cree writer, political leader, teacher, negotiator, and lawyer. Throughout his career he advocated, on behalf of all First Nation peoples, for the right to be "the red tile in the Canadian mosaic."

David Laird, was a Canadian politician. He was born in New Glasgow, Prince Edward Island, into a Presbyterian family noted for its civic activism. His father Alexander had been a long time Reformer and Liberal MLA. David became a Liberal MLA for Belfast. He also established and edited The Patriot.

Treaty 4 is a treaty established between Queen Victoria and the Cree and Saulteaux First Nation band governments. The area covered by Treaty 4 represents most of current day southern Saskatchewan, plus small portions of what are today western Manitoba and southeastern Alberta. This treaty is also called the Qu'Appelle Treaty, as its first signings were conducted at Fort Qu'Appelle, North-West Territories, on 15 September 1874. Additional signings or adhesions continued until September 1877. This treaty is the only indigenous treaty in Canada that has a corresponding indigenous interpretation.

The Sweetgrass First Nation is a Cree First Nation reserve in Cut Knife, Saskatchewan, Canada. Their territory is located 35 kilometers west of Battleford. The reserve was established when Chief Sweetgrass signed Treaty 6 on September 9, 1876, with the Fort Pitt Indians. Chief Sweetgrass was killed six months after signing Treaty 6, after which Sweetgrass's son, Apseenes, succeeded him. Apseenes was unsuccessful in leading the band so chiefdom was handed over to Wah-wee-kah-oo-tah-mah-hote after he signed Treaty 6 in 1876 at Fort Carlton. Wah-wee-kah-oo-tah-mah-hote served as chief between 1876 and 1883 but was deposed and Apseenes took over chiefdom.

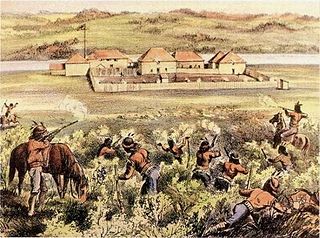

Fort Pitt Provincial Park is a provincial park in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. It includes the site of Fort Pitt, a trading post built in 1829 by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) on the North Saskatchewan River in Rupert's Land. It was built at the direction of Chief Factor John Rowand, previously of Fort Edmonton, to trade goods for bison hides, meat and pemmican. Pemmican, dried buffalo meat, was required as provisions for HBC's northern trading posts.

History of Saskatchewan encompasses the study of past human events and activities of the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, the middle of Canada's three prairie provinces. Archaeological studies give some clues as to the history and lifestyles of the Palaeo-Indian, Taltheilei, and Shield Archaic traditions who were the first occupants of the prehistoric era of this geographical area. They evolved into the history of the First Nations people who kept their history alive in oral tradition. The First Nation bands that were a part of this area were the Chipewyan, Cree, Saulteaux, Assiniboine, Atsina, and Sioux.

The Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN), formerly known as the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations, is a Saskatchewan-based First Nations organization. It represents 74 First Nations in Saskatchewan and is committed to honouring the spirit and intent of the Numbered Treaties, as well as the promotion, protection and implementation of these promises made over a century ago.

Ahtahkakoop First Nation is a Cree First Nation band government in Shell Lake, Saskatchewan, Canada belonging to the Wāskahikaniwiyiniwak division of nēhiyawak. The Ahtahkakoop First Nation government and community is located on Ahtahkakoop 104, 72 kilometers northwest of Prince Albert and is 17,347 hectares in size. The community was formerly known as the "Sandy Lake Indian Band", a name which is still used interchangeably when referring to the reserve.

Muskowekwan First Nation is a Saulteaux (Ojibway) First Nation who inhabit approximately 100 km northwest of Melville, Saskatchewan, Canada. As of May, 2008, the First Nation has 1,517 registered people, of which their on-reserve population was 400.

The Iron Confederacy or Iron Confederation was a political and military alliance of Plains Indians of what is now Western Canada and the northern United States. This confederacy included various individual bands that formed political, hunting and military alliances in defense against common enemies. The ethnic groups that made up the Confederacy were the branches of the Cree that moved onto the Great Plains around 1740, the Saulteaux, the Nakoda or Stoney people also called Pwat or Assiniboine, and the Métis and Haudenosaunee. The Confederacy rose to predominance on the northern Plains during the height of the North American fur trade when they operated as middlemen controlling the flow of European goods, particularly guns and ammunition, to other Indigenous nations, and the flow of furs to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) and North West Company (NWC) trading posts. Its peoples later also played a major part in the bison (buffalo) hunt, and the pemmican trade. The decline of the fur trade and the collapse of the bison herds sapped the power of the Confederacy after the 1860s, and it could no longer act as a barrier to U.S. and Canadian expansion.

Carry the Kettle Nakoda Nation is a Nakota (Assiniboine) First Nation in Canada located about 80 km (50 mi) east of Regina, Saskatchewan and 13 km (8.1 mi) south of Sintaluta. The reservation is in Treaty 4 territory.

The pass system was a system of internal passports for Indigenous Canadians between 1885 and 1941. It was administered by the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA), beginning after the 1885 North-West Rebellion as part of a broader effort to confine indigenous people to Indian reserves, then newly formed through the Numbered Treaties. The system, initially intended as a temporary measure to quell disorder in the prairie provinces, eventually became a permanent feature of federal Indian affairs policy.

In the 16th century Samuel de Champlain and Gabriel Sagard recorded that the Iroquois and Huron cultivated the soil for maize or "Indian corn". Maize, beans (phaseolus), squash (Cucurbita) and the sunflower were grown throughout agricultural lands in North America by the 16th century. As early as 2300 BC evidence of squash was introduced to the northeastern woodlands region. Archaeological findings from 500 AD have shown corn cultivation in southern Ontario.

Sarah Alexandra Carter is a Canadian historian. She is Professor and the Henry Marshall Tory Chair at the University of Alberta in both the Department of History and Classics and the Faculty of Native Studies with noted specialties in Indigenous and women's history.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cuthand, Doug. "Peasant Farm Policy". The Canadian Encyclopedia .

- ↑ Whitehouse-Strong, Derek (Winter 2007). ""Everything Promised Had Been Included In The Writing" Indian Reserve Farming And The Spirit And Intent Of Treaty Six Reconsidered". Great Plains Quarterly. 27 (1): 26. Archived from the original on August 5, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Carter, Sarah (2007). "'We Must Farm to Enable Us to Live': The Plains Cree and Agriculture to 1900". In Kitzan, Chris; Francis, R. Douglas (eds.). The Prairie West as Promised Land (PDF).

- ↑ "Peasant Farming Policy". gladue.usask.ca. Gladue Rights Research Database. Archived from the original on August 7, 2023. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- 1 2 Hildebrandt, Walter (2008). Views From Fort Battleford Constructed Visions of an Anglo-Canadian West. Athabasca: Athabasca University Press. pp. 95–96. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.