Alfonso XII, also known as El Pacificador, was King of Spain from 29 December 1874 to his death in 1885.

1874 (MDCCCLXXIV) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Gregorian calendar and a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar, the 1874th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 874th year of the 2nd millennium, the 74th year of the 19th century, and the 5th year of the 1870s decade. As of the start of 1874, the Gregorian calendar was 12 days ahead of the Julian calendar, which remained in localized use until 1923.

Carlism is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty, one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855), on the Spanish throne.

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: the conservative and devolutionist supporters of the late king's brother, Carlos de Borbón, became known as Carlists (carlistas), while the progressive and centralist supporters of the regent, Maria Christina, acting for Isabella II of Spain, were called Liberals (liberales), cristinos or isabelinos. Aside from being a war of succession about the question who the rightful successor to King Ferdinand VII of Spain was, the Carlists' goal was the return to a traditional monarchy, while the Liberals sought to defend the constitutional monarchy.

The Third Carlist War, which occurred from 1872 to 1876, was the last Carlist War in Spain. It is sometimes referred to as the "Second Carlist War", as the earlier "Second" War (1847–1849) was smaller in scale and relatively trivial in political consequence.

Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma and Piacenza was the head of the ducal House of Bourbon-Parma from 1977 until his death. Carlos Hugo was a Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain and sought to change the political direction of the Carlist movement through the Carlist Party, of which he was the official head during the fatal Montejurra incidents. His marriage to Princess Irene of the Netherlands in 1964 caused a constitutional crisis in the Netherlands.

Jaime de Borbón y de Borbón-Parma, known as Duke of Madrid, was the Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain under the name Jaime III and the holder of the Legitimist claim to the throne of France as Jacques I.

Prince Sixtus Henry of Bourbon-Parma, known as Enrique V by supporters, is considered Regent of Spain by some Carlists who accord him the titles Duke of Aranjuez, Infante of Spain, and Standard-bearer of Tradition. His heir is Henri, Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

Xavier, Duke of Parma and Piacenza, known in France before 1974 as Prince Xavier de Bourbon-Parme, known in Spain as Francisco Javier de Borbón-Parma y de Braganza or simply as Don Javier, was head of the ducal House of Bourbon-Parma. He is best known as dynastic leader of Carlism and the Carlist pretender to the throne of Spain, since 1936 as a regent-claimant and since 1952 as a claimant, appearing under the name Javier I. Since 1974, he was pretender to the defunct throne of Parma. He is also recognized as involved in the so-called Sixtus Affair of 1916–1917 and in the so-called Halifax-Chevalier talks of 1940.

The Guerrilleros de Cristo Rey was a far-right paramilitary organisation active in the late 1970s in Spain, primarily in the Basque Country and Madrid, but also in Navarre.

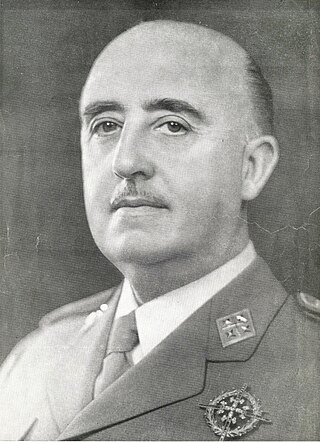

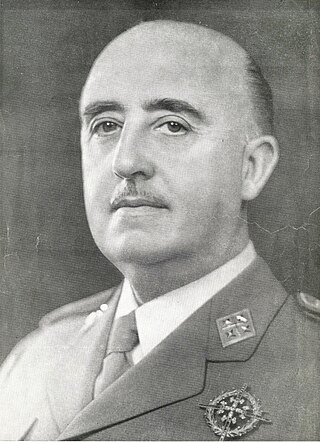

The Carlist Party is a Spanish political party that considers itself as a successor to the historical tradition of Carlism. The party was founded in 1970, although it remained illegal until 1977 following the death of the caudillo Francisco Franco and the democratisation of Spain.

Infanta Blanca of Spain was the eldest child of Infante Carlos, Duke of Madrid, Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain and his wife Princess Margherita of Bourbon-Parma. Blanca was a member of the House of Bourbon and - according to the Carlists - an Infanta of Spain by birth. In 1889 she married Archduke Leopold Salvator of Austria, Prince of Tuscany. The couple had ten children. The family left Austria after the end of the Monarchy and finally settled in Barcelona. When the male line of Blanca's family died out at the death of her uncle, Alfonso Carlos, Duke of San Jaime, some of the Carlists recognized her as the legitimate heiress to the Spanish throne.

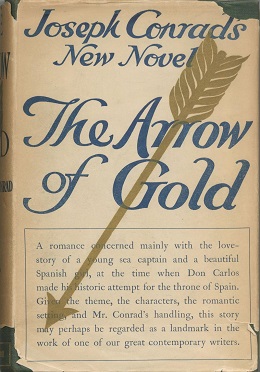

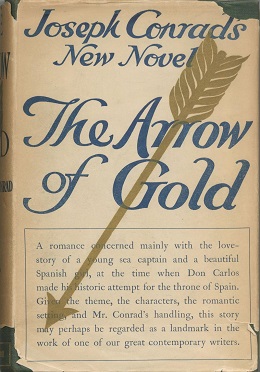

The Arrow of Gold is a novel by Joseph Conrad, published in 1919. It was originally titled "The Laugh" and published serially in Lloyd's Magazine from December 1918 to February 1920. The story is set in Marseille in the 1870s during the Third Carlist War. The characters of the novel are supporters of the Spanish Pretender Carlos, Duke of Madrid. The novel features a person referred to as "Lord X", whose activities as arms smuggler resemble those of the Carlist politician Tirso de Olazábal y Lardizábal, Count of Arbelaiz.

José María Valiente Soriano (1900-1982) was a Spanish politician. He commenced his career in Acción Nacional and gained recognition as leader of Juventudes de Acción Popular, the youth branch of CEDA. In 1935 he joined Carlism; his political climax fell on the period of 1955-1967, when he was leading the mainstream Traditionalist organisation. After 1971 he unsuccessfully engaged in buildup of conservative monarchist groupings. He served in the Republican parliament during two terms between 1933 and 1936; between 1967 and 1977 during two terms he held a mandate in the Francoist Cortes. In 1937-1942 he was member of Consejo Nacional of Falange Española Tradicionalista.

Traditionalism is a Spanish political doctrine formulated in the early 19th century and developed until today. It understands politics as implementing Catholic social teaching and the social kingship of Jesus Christ, with Catholicism as the state religion and Catholic religious criteria regulating public morality and every legal aspect of Spain. In practical terms it advocates a loosely organized monarchy combined with strong royal powers, with some checks and balances provided by organicist representation, and with society structured on a corporative basis. Traditionalism is an ultra-reactionary doctrine; it rejects concepts such as democracy, human rights, constitution, universal suffrage, sovereignty of the people, division of powers, religious liberty, freedom of speech, equality of individuals, and parliamentarism. The doctrine was adopted as the theoretical platform of the Carlist socio-political movement, though it appeared also in a non-Carlist incarnation. Traditionalism has never exercised major influence among the Spanish governmental strata, yet periodically it was capable of mass mobilization and at times partially filtered into the ruling practice.

The Unification Decree was a political measure adopted by Francisco Franco in his capacity of Head of State of Nationalist Spain on April 19, 1937. The decree merged two existing political groupings, the Falangists and the Carlists, into a new party - the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista. As all other parties were declared dissolved at the same time, the FET became the only legal party in Nationalist Spain. It was defined in the decree as a link between state and society and was intended to form the basis for an eventual totalitarian regime. The head of state – Franco himself – was proclaimed party leader, to be assisted by the Junta Política and Consejo Nacional. A set of decrees which followed shortly after appointed members to the new executive.

Margaritas in the Spanish Civil War played an important role for Nationalist forces. Created in 1919 as a Carlist social aid organization for the poor, they went into decline during the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera as there was less of a perceived need for promotion of their ideals.

Carlo-francoism was a branch of Carlism which actively engaged in the regime of Francisco Franco. Though mainstream Carlism retained an independent stand, many Carlist militants on their own assumed various roles in the Francoist system, e.g. as members of the FET y de las JONS executive, Cortes procuradores, or civil governors. The Traditionalist political faction of the Francoist regime issued from Carlism particularly held tight control over the Ministry of Justice. They have never formed an organized structure, their dynastical allegiances remained heterogeneous and their specific political objectives might have differed. Within the Francoist power strata, the carlo-francoists remained a minority faction that controlled some 5% of key posts; they failed to shape the regime and at best served as counter-balance to other groupings competing for power.

Princess Cécile Marie Antoinette Madeleine Jeanne Agnès Françoise of Bourbon-Parma, Countess of Poblet was a French humanitarian and political activist. A Carlist, she supported the claims of her father, Prince Xavier, Duke of Parma and Piacenza, to the headship of the House of Bourbon-Parma and his claim to the Spanish throne. She later supported the claim of her older brother, Prince Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma and his progressive reforms to Carlist ideology over that of her younger brother Prince Sixtus Henry, Duke of Aranjuez's claims and traditionalist stance. An anti-fascist, she opposed the dictatorship of Francisco Franco and was expelled from Spain multiple times for working to promote democratic reforms. During her exile, she made connections in French intellectual circles and attending the 1973 World Congress of Peace Forces and 1974 Berlin Conference. She was present, along with some of her siblings, at the Montejurra massacre in 1976.

Princess Marie des Neiges Madeleine Françoise of Bourbon-Parma, Countess of Castillo de la Mota is a French aristocrat, ornithologist, and Carlist activist. She is the youngest daughter of Prince Xavier, Duke of Parma and Madeleine de Bourbon-Busset. A progressive Carlist, she supported the liberal reforms to the party made by her elder brother, Prince Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma, and rejected the conservative faction of the party created by her younger brother, Prince Sixtus Henry, Duke of Aranjuez. In her youth, she was a prominent socialite in Parisian society. Marie des Neiges has a doctorate in biology and worked as an ornithologist. She is a recipient of the Grand Cross of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George and the Grand Cross of the Order of Prohibited Legitimacy.