Related Research Articles

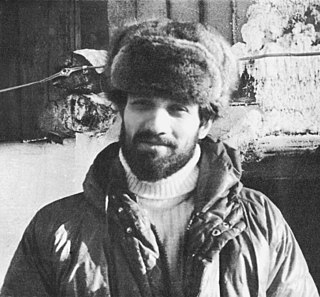

Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky was a Russian-born British human rights activist and writer. From the late 1950s to the mid-1970s, he was a prominent figure in the Soviet dissident movement, well known at home and abroad. He spent a total of twelve years in the psychiatric prison-hospitals, labour camps, and prisons of the Soviet Union during Brezhnev rule.

There was systematic political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union, based on the interpretation of political opposition or dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

Viktor Aleksandrovich Nekipelov was a Soviet Russian poet, writer, Soviet dissident, and a member of the Moscow Helsinki Group. He spent about nine years in prison for his participation in the Moscow Helsinki Group.

Galina Vasilyevna Starovoitova was a Soviet dissident, Russian politician and ethnographer known for her work to protect ethnic minorities and promote democratic reforms in Russia. She was shot to death in her apartment building in 1998.

A Chronicle of Current Events was one of the longest running samizdat periodicals of the post-Stalinist Soviet Union. This unofficial newsletter reported violations of civil rights and judicial procedure by the Soviet government and responses to those violations by citizens across the Soviet Union. Appearing first in April 1968, it soon became the main voice of the Soviet human rights movement, inside the country and abroad.

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term dissident was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960s until the Fall of Communism. It was used to refer to small groups of marginalized intellectuals whose challenges, from modest to radical to the Soviet regime, met protection and encouragement from correspondents, and typically criminal prosecution or other forms of silencing by the authorities. Following the etymology of the term, a dissident is considered to "sit apart" from the regime. As dissenters began self-identifying as dissidents, the term came to refer to an individual whose non-conformism was perceived to be for the good of a society. The most influential subset of the dissidents is known as the Soviet human rights movement.

Marina Yevgenyevna Salye was a Russian geologist and politician, being the former deputy of the legislative assembly of Leningrad. She was also a people's deputy in the Congress of People's Deputies of the RSFSR until September 1993, when the congress was dissolved. Salye was one of the leaders of the radical pro-reform group called Radical Democrats.

Author and publisher Valery Nikolaevich Chalidze was a Soviet dissident and human rights activist, deprived of his USSR citizenship in 1972 while on a visit to the US.

Alexander Pinkhosovich Podrabinek is a Soviet dissident, journalist and commentator. During the Soviet period he was a human rights activist, being exiled, then imprisoned in a corrective-labour colony, for publication of his book Punitive Medicine in Russian and in English.

Andrei Snezhnevsky was a Soviet psychiatrist whose name was lent to the unbridled broadening of the diagnostic borders of schizophrenia in the Soviet Union, the key architect of the Soviet concept of sluggish schizophrenia, the inventor of the term "sluggish schizophrenia", an embodier of history of repressive psychiatry, and a direct participant in psychiatric repression against dissidents.

Lyudmila Mikhaylovna Alexeyeva was a Russian historian and human-rights activist who was a founding member in 1976 of the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group and one of the last Soviet dissidents active in post-Soviet Russia.

Anatoly Ivanovich Koryagin is a psychiatrist and Soviet dissident. He holds a Candidate of Science degree. Along with others, he exposed political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union. He pointed out Russia constructed psychiatric prisons to punish dissidents.

Global Initiative on Psychiatry (GIP) is an international foundation for mental health reform which took part in the campaign against the political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR. The organization is of NGO type.

Sergei Adamovich Kovalyov was a Russian human rights activist and politician. During the Soviet period he was a dissident and, after 1975, a political prisoner.

In the Soviet Union, systematic political abuse of psychiatry took place and was based on the interpretation of political dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

In the Soviet Union, a systematic political abuse of psychiatry took place and was based on the interpretation of political dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

The Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes was an offshoot of the Moscow Helsinki Group and a key source of information on psychiatric repression in the Soviet Union.

In 1965 a human rights movement emerged in the USSR. Those actively involved did not share a single set of beliefs. Many wanted a variety of civil rights — freedom of expression, of religious belief, of national self-determination. To some it was crucial to provide a truthful record of what was happening in the country, not the heavily censored version provided in official media outlets. Others still were "reform Communists" who thought it possible to change the Soviet system for the better.

Sergei Ivanovich Grigoryants was a Soviet dissident and political prisoner, journalist, literary critic, chairman of the Glasnost Defense Foundation. He was imprisoned for ten years in Chistopol jail as a political prisoner for anti-Soviet activities, from 1975 to 1980 and then four more years starting in 1983 on similar charges.

Marina Voikhanskaya is a Soviet-British psychiatrist who opposed the detention of patients who were committed to Soviet psychiatric hospitals for their beliefs, and not for mental health reasons. She migrated to the UK in 1975 and campaigned against the abuse of psychiatry for political purposes and for the release of her son Misha from the Soviet Union. She lives in Cambridge, UK.

References

- ↑ "Peter Reddaway". elliott.gwu.edu. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ↑ "Dissent in the Soviet Union". Dissent. Spring 1976.

- ↑ "- CORRUPTION IN RUSSIA". www.govinfo.gov. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ↑ "Market Bolshevism against Democracy | Wilson Center". www.wilsoncenter.org. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ↑ The Economist: "A chronicle of heroism in the Soviet Union" - review of The Dissidents, 11 April 2020