The Lumière brothers, Auguste Marie Louis Nicolas Lumière and Louis Jean Lumière, were French manufacturers of photography equipment, best known for their Cinématographe motion picture system and the short films they produced between 1895 and 1905, which places them among the earliest filmmakers.

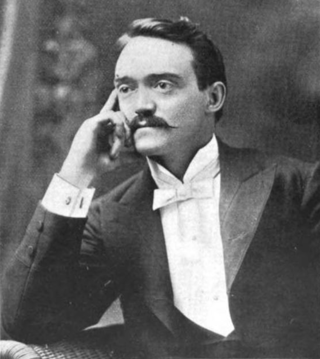

William Kennedy Laurie Dickson was a British inventor who devised an early motion picture camera under the employment of Thomas Edison.

The following is an overview of the events of 1895 in film, including a list of films released and notable births.

The following is an overview of the events of 1896 in film, including a list of films released and notable births.

The following is an overview of the events of 1894 in film, including a list of films released and notable births.

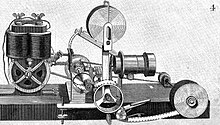

The Kinetoscope is an early motion picture exhibition device, designed for films to be viewed by one person at a time through a peephole viewer window. The Kinetoscope was not a movie projector, but it introduced the basic approach that would become the standard for all cinematic projection before the advent of video: it created the illusion of movement by conveying a strip of perforated film bearing sequential images over a light source with a high-speed shutter. First described in conceptual terms by U.S. inventor Thomas Edison in 1888, it was largely developed by his employee William Kennedy Laurie Dickson between 1889 and 1892. Dickson and his team at the Edison lab in New Jersey also devised the Kinetograph, an innovative motion picture camera with rapid intermittent, or stop-and-go, film movement, to photograph movies for in-house experiments and, eventually, commercial Kinetoscope presentations.

Charles Francis Jenkins was an American engineer who was a pioneer of early cinema and one of the inventors of television, though he used mechanical rather than electronic technologies. His businesses included Charles Jenkins Laboratories and Jenkins Television Corporation. Over 400 patents were issued to Jenkins, many for his inventions related to motion pictures and television.

Thomas J. Armat was an American mechanic and inventor, a pioneer of cinema best known through the co-invention of the Edison Vitascope.

Cinematograph or kinematograph is an early term for several types of motion picture film mechanisms. The name was used for movie cameras as well as film projectors, or for complete systems that also provided means to print films.

Major Woodville Latham (1837–1911) was an ordnance officer of the Confederacy during the American Civil War and professor of chemistry at West Virginia University. He was significant in the development of early film technology.

Vitascope was an early film projector first demonstrated in 1895 by Charles Francis Jenkins and Thomas Armat. They had made modifications to Jenkins' patented Phantoscope, which cast images via film and electric light onto a wall or screen. The Vitascope is a large electrically-powered projector that uses light to cast images. The images being cast are originally taken by a kinetoscope mechanism onto gelatin film. Using an intermittent mechanism, the film negatives produced up to fifty frames per second. The shutter opens and closes to reveal new images. This device can produce up to 3,000 negatives per minute. With the original Phantoscope and before he partnered with Armat, Jenkins displayed the earliest documented projection of a filmed motion picture in June 1894 in Richmond, Indiana.

Herman Casler was an American inventor and co-founder of the partnership called the K.M.C.D. Syndicate, along with W.K-L. Dickson, Elias Koopman, and Henry Marvin, which eventually was incorporated into the American Mutoscope Company in December 1895.

Cinéorama was an early film experiment and amusement ride presented for the first time at the 1900 Paris Exposition. It was invented by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson and it simulated a ride in a hot air balloon over Paris. It represented a union of the earlier technology of panoramic paintings and the recently invented technology of cinema. It worked by means of a circulatory screen that projects images helped by ten synchronized projectors.

The decade of the 1890s in film involved some significant events.

The Latham Loop is used in film projection and image capture. It isolates the filmstrip from vibration and tension, allowing movies to be continuously shot and projected for extended periods.

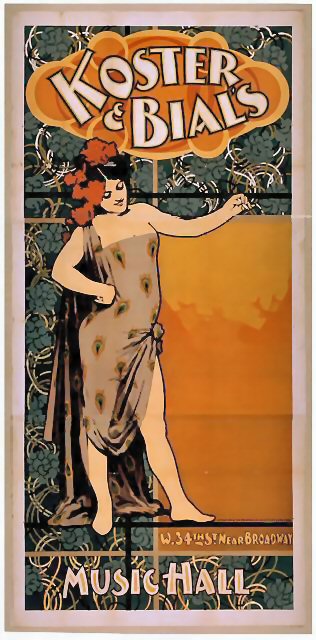

Koster and Bial's Music Hall was an important vaudeville theatre in New York City, located at Broadway and Thirty-Fourth Street, where Macy's flagship store now stands. It had a seating capacity of 3,748, twice the size of many theaters. Ticket prices ranged from 25¢ for a seat in the gallery to $1.50 for one in the orchestra. The venue was founded by John Koster (1844-1895) and Albert Bial (1842-1897) in the late 19th century and closed in 1901.

Henri Joly (1866–1945) was a French inventor and businessman. He developed early versions of motion picture film, cameras, and projectors.

The history of film technology traces the development of techniques for the recording, construction and presentation of motion pictures. When the film medium came about in the 19th century, there already was a centuries old tradition of screening moving images through shadow play and the magic lantern that were very popular with audiences in many parts of the world. Especially the magic lantern influenced much of the projection technology, exhibition practices and cultural implementation of film. Between 1825 and 1840, the relevant technologies of stroboscopic animation, photography and stereoscopy were introduced. For much of the rest of the century, many engineers and inventors tried to combine all these new technologies and the much older technique of projection to create a complete illusion or a complete documentation of reality. Colour photography was usually included in these ambitions and the introduction of the phonograph in 1877 seemed to promise the addition of synchronized sound recordings. Between 1887 and 1894, the first successful short cinematographic presentations were established. The biggest popular breakthrough of the technology came in 1895 with the first projected movies that lasted longer than 10 seconds. During the first years after this breakthrough, most motion pictures lasted about 50 seconds, lacked synchronized sound and natural colour, and were mainly exhibited as novelty attractions. In the first decades of the 20th century, movies grew much longer and the medium quickly developed into one of the most important tools of communication and entertainment. The breakthrough of synchronized sound occurred at the end of the 1920s and that of full color motion picture film in the 1930s. By the start of the 21st century, physical film stock was being replaced with digital film technologies at both ends of the production chain by digital image sensors and projectors.

Norman C. Raff and Frank R. Gammon were two American businessmen who were known for distributing and promoting some of the Edison Studio films, and founding their own business, which was called The Kinetoscope Company.