Related Research Articles

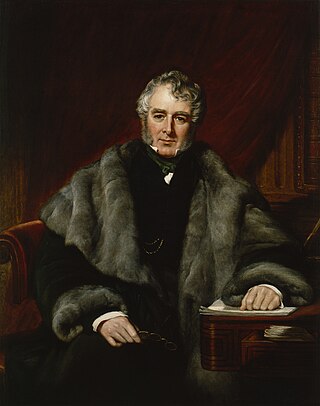

Henry William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne was a British Whig politician who served as the Home Secretary and twice as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

The Whigs were a political party in the Parliaments of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. Between the 1680s and the 1850s, the Whigs contested power with their rivals, the Tories. The Whigs became the Liberal Party when it merged with the Peelites and Radicals in the 1850s. Many Whigs left the Liberal Party in 1886 over the issue of Irish Home Rule to form the Liberal Unionist Party, which merged into the Conservative Party in 1912.

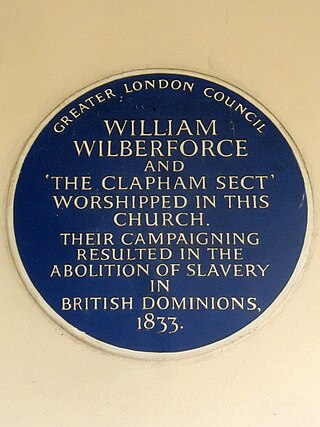

The Clapham Sect, or Clapham Saints, were a group of social reformers associated with Holy Trinity Clapham in the period from the 1780s to the 1840s. Despite the label "sect", most members remained in the established Church of England, which was highly interwoven with offices of state. However, its successors were in many cases outside of the established Anglican Church.

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, was a British historian, poet, and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster General between 1846 and 1848.

Sir James Mackintosh FRS FRSE was a Scottish jurist, Whig politician and Whig historian. His studies and sympathies embraced many interests. He was trained as a doctor and barrister, and worked also as a journalist, judge, administrator, professor, philosopher and politician.

George Macaulay Trevelyan was a British historian and academic. He was a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1898 to 1903. He then spent more than twenty years as a full-time author. He returned to the University of Cambridge and was Regius Professor of History from 1927 to 1943. He served as Master of Trinity College from 1940 to 1951. In retirement, he was Chancellor of Durham University.

Whig history is an approach to historiography that presents history as a journey from an oppressive and benighted past to a "glorious present". The present described is generally one with modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy: it was originally a term for the metanarratives praising Britain's adoption of constitutional monarchy and the historical development of the Westminster system. The term has also been applied widely in historical disciplines outside of British history to describe "any subjection of history to what is essentially a teleological view of the historical process". When the term is used in contexts other than British history, "whig history" (lowercase) is preferred.

Social change is the alteration of the social order of a society which may include changes in social institutions, social behaviours or social relations. Sustained at a larger scale, it may lead to social transformation or societal transformation.

The Radicals were a loose parliamentary political grouping in Great Britain and Ireland in the early to mid-19th century who drew on earlier ideas of radicalism and helped to transform the Whigs into the Liberal Party.

Hugh Fortescue, 2nd Earl Fortescue KG, PC, styled Viscount Ebrington from 1789 to 1841, was a British Whig politician.

Catharine Macaulay, was an English Whig republican historian.

In the beginning of 19th century, Lord William Bentinck, then-Governor-general speculated that the possibility of vast change occurring in the frame of society would eventually lead to the British leaving the country under capable Indian rule. But he also added that such changes should not be expected for centuries to come.

Progress is movement towards a refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. It is central to the philosophy of progressivism, which interprets progress as the set of advancements in technology, science, and social organization efficiency – the latter being generally achieved through direct societal action, as in social enterprise or through activism, but being also attainable through natural sociocultural evolution – that progressivism holds all human societies should strive towards.

The Days of May was a period of significant social unrest and political tension in the United Kingdom in May 1832, after the Tories blocked the Third Reform Bill in the House of Lords, which aimed to extend parliamentary representation to the middle and working classes as well as the newly industrialised cities of the English Midlands and the North of England.

The Ultra-Tories were an Anglican faction of British and Irish politics that appeared in the 1820s in opposition to Catholic emancipation. The faction was later called the "extreme right-wing" of British and Irish politics.

Technological determinism is a reductionist theory in assuming that a society's technology progresses by following its own internal logic of efficiency, while determining the development of the social structure and cultural values. The term is believed to have originated from Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929), an American sociologist and economist. The most radical technological determinist in the United States in the 20th century was most likely Clarence Ayres who was a follower of Thorstein Veblen as well as John Dewey. William Ogburn was also known for his radical technological determinism and his theory on cultural lag.

Thomas Walker (1749–1817) was an English cotton merchant and political radical.

The historiography of the United Kingdom includes the historical and archival research and writing on the history of the United Kingdom, Great Britain, England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. For studies of the overseas empire see historiography of the British Empire.

Peel's Bill, or the Resumption of Cash Payments Act 1819, marked the return of the British currency to the gold standard, after the Bank Restriction Act 1797 saw paper money replacing convertibility to gold and silver under the financial pressures of the French Revolutionary Wars.

The March of Intellect, or the 'March of mind', was the subject of heated debate in early nineteenth-century England, one side welcoming the progress of society towards greater, and more widespread, knowledge and understanding, the other deprecating the modern mania for progress and for new-fangled ideas.

References

- ↑ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad, & Dangerous People? (London 2007) pp. 348, 608–09

- ↑ J. Boyd, Science and Whig Manners (2009) p. 76

- ↑ M. Isabella, Risorgimento in Exile (2009) p. 115

- ↑ Quoted in J. Burrow, A History of Histories (Penguin 2009) p. 368

- ↑ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad, & Dangerous People? (London 2007) p. 350

- ↑ B. Hilton, A Mad, Bad, & Dangerous People? (London 2007) p. 352

- ↑ B. Wilson, Decency and Disorder (London 2007) pp. 316, 326

- ↑ J. Buchan, The Complete Short Stories II (1997) p. 75