Jean-Jacques Barthélemy was a French scholar who became the first person to decipher an extinct language. He deciphered the Palmyrene alphabet in 1754 and the Phoenician alphabet in 1758.

Nestor Léon Marchand was a French medical doctor, pharmacist, and botanist. He is known for his studies of the flowering plant family Anacardiaceae.

Acanthina, common name the unicorn snails, is a genus of small predatory sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Muricidae, the murex snails or rock snails.

Chicoreus virgineus, common name the virgin murex, is a species of sea snail, a marine gastropod mollusk in the family Muricidae, the murex snails or rock snails.

Pseudosimnia carnea, common name the dwarf red egg shell, is a species of sea snail, a marine gastropod mollusk in the family Ovulidae, the ovulids, cowry allies or false cowries.

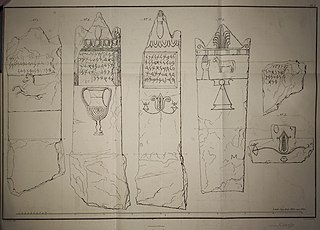

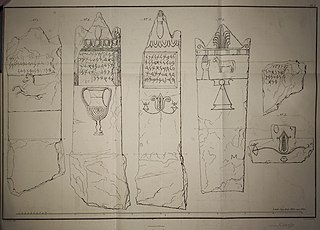

The Punic-Libyan bilingual inscriptions are two important ancient bilingual inscriptions dated to the 2nd century BC.

Jacques-Eugène Armengaud was a French industrial engineer, and professor of machine drawing at the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers (CNAM), particularly known as the original author of The practical draughtsman's book of industrial design, 1851.

The Assyrian lion weights are a group of bronze statues of lions, discovered in archaeological excavations in or adjacent to ancient Assyria.

The Bodashtart inscriptions are a well-known group of between 22 and 24 Phoenician inscriptions from the 6th century BC referring to King Bodashtart.

The Yehawmilk stele, de Clercq stele, or Byblos stele, also known as KAI 10 and CIS I 1, is a Phoenician inscription from c.450 BC found in Byblos at the end of Ernest Renan's Mission de Phénicie. Yehawmilk, king of Byblos, dedicated the stele to the city’s protective goddess Ba'alat Gebal.

The Carpentras Stele is a stele found at Carpentras in southern France in 1704 that contains the first published inscription written in the Phoenician alphabet, and the first ever identified as Aramaic. It remains in Carpentras, at the Bibliothèque Inguimbertine, in a "dark corner" on the first floor. Older Aramaic texts were found since the 9th century BC, but this one is the first Aramaic text to be published in Europe. It is known as KAI 269, CIS II 141 and TAD C20.5.

Carthaginian tombstones are Punic language-inscribed tombstones excavated from the city of Carthage over the last 200 years. The first such discoveries were published by Jean Emile Humbert in 1817, Hendrik Arent Hamaker in 1828 and Christian Tuxen Falbe in 1833.

The Athenian Greek-Phoenician inscriptions are 18 ancient Phoenician inscriptions found in the region of Athens, Greece. They represent the second largest group of foreign inscriptions in the region after the Thracians. 9 of the inscriptions are bilingual Phoenician-Greek and written on steles. Almost all of them bear the indication of the deceased's city of origin, not just the more general designation of their ethnicity, like most other non-Greek inscriptions in the region.

The Idalion Temple inscriptions are six Phoenician inscriptions found by Robert Hamilton Lang in his excavations at the Temple of Idalium in 1869, whose work there had been inspired by the discovery of the Idalion Tablet in 1850. The most famous of these inscriptions is known as the Idalion bilingual. The Phoenician inscriptions are known as KAI 38-40 and CIS I 89-94.

Auguste Louis Brot was a Swiss malacologist (conchologist).

Julius Euting was a German Orientalist.

The Baalshamem inscription is a Phoenician inscription discovered in 1860–61 at Umm al-Amad, Lebanon, the longest of three inscriptions found there during Ernest Renan's Mission de Phénicie. All three inscriptions were found on the north side of the hill; this inscription was found in the foundation of one of the ruined houses covering the hill.

The Phoenician Adoration steles are a number of Phoenician and Punic steles depicting the adoration gesture (orans).

The Banobal stele is a Horus on the Crocodiles stele with a Phoenician graffiti inscription on a block of marble which served as a base for an Egyptian stele, found near the Pyramid of Unas in Memphis, Egypt in 1900. The inscription is known as KAI 48 or RES 1.

The Kition Resheph pillars are two Phoenician inscriptions discovered in Cyprus at Kition in 1860. They are notable for mentioning three cities - Kition, Idalion and Tamassos.