Related Research Articles

Johannes Gerhardus Strijdom, also known as Hans Strijdom and nicknamed the Lion of the North or the Lion of Waterberg, was a South African politician and the fifth prime minister of South Africa from 30 November 1954 to his death on 24 August 1958. He was an uncompromising Afrikaner nationalist and a member of the largest, baasskap faction of the National Party (NP), who further accentuated the NP's apartheid policies and break with the Union of South Africa in favour of a republic during his rule.

The Griquas are a subgroup of mixed-race heterogeneous formerly Xiri-speaking nations in South Africa with a unique origin in the early history of the Dutch Cape Colony. Like the Boers they migrated inland from the Cape and in the 19th century established several states in what is now South Africa and Namibia. The Griqua consider themselves as being South Africa’s first multiracial nation with people descended directly from Dutch settlers in the Cape, and local peoples.

Stellenbosch University (SU) (Afrikaans: Universiteit Stellenbosch, Xhosa: iYunivesithi yaseStellenbosch) is a public research university situated in Stellenbosch, a town in the Western Cape province of South Africa. Stellenbosch is the oldest university in South Africa and the oldest extant university in Sub-Saharan Africa, which received full university status in 1918. Stellenbosch University designed and manufactured Africa's first microsatellite, SUNSAT, launched in 1999.

The Congress of South African Trade Unions is a trade union federation in South Africa. It was founded in 1985 and is the largest of the country's three main trade union federations, with 21 affiliated trade unions.

Fatima Meer was a South African writer, academic, screenwriter, and prominent anti-apartheid activist.

Helen Beatrice Joseph OMSG was a South African anti-apartheid activist. Born in Sussex, England, Helen graduated with a degree in English from the University of London in 1927 and then departed for India, where she taught for three years at Mahbubia School for girls in Hyderabad. In about 1930 she left India for England via South Africa. However, she settled in Durban, where she met and married a dentist, Billie Joseph, whom she later divorced.

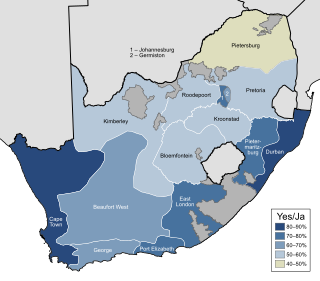

A referendum on ending apartheid was held in South Africa on 17 March 1992. The referendum was limited to white South African voters, who were asked whether or not they supported the negotiated reforms begun by State President F. W. de Klerk two years earlier, in which he proposed to end the apartheid system that had been implemented since 1948. The result of the election was a large victory for the "yes" side, which ultimately resulted in apartheid being lifted. Universal suffrage was introduced two years later for the country's first non-racial elections.

The National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) was an important force for liberalism and later radicalism in South African student anti-apartheid politics. Its mottos included non-racialism and non-sexism.

Indian South Africans are South Africans who descend from indentured labourers and free migrants who arrived from British India during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The majority live in and around the city of Durban, making it one of the largest ethnically Indian-populated cities outside of India.

Omar Badsha is a South African documentary photographer, artist, political and trade union activist and historian. He is a self-taught artist. He has exhibited his art in South Africa and internationally. In 2015, he won the Arts & Culture Trust (ACT) Lifetime Achievement Award for Visual Art. In 2017, he received an honorary doctorate Doctor of Philosophy (DPhil), for his groundbreaking work in the field of documentary photography in South Africa. He was also awarded a Presidential honor The Order of Ikhamanga in Silver for "His commitment to the preservation of our country’s history through ground-breaking and well-balanced research, and collection of profiles and events of the struggle for liberation"

The Federation of South African Trade Unions (FOSATU) was a trade union federation in South Africa.

Internal resistance to apartheid in South Africa originated from several independent sectors of South African society and took forms ranging from social movements and passive resistance to guerrilla warfare. Mass action against the ruling National Party (NP) government, coupled with South Africa's growing international isolation and economic sanctions, were instrumental in leading to negotiations to end apartheid, which began formally in 1990 and ended with South Africa's first multiracial elections under a universal franchise in 1994.

Richard Turner, known as Rick Turner, was a South African academic and anti-apartheid activist who was murdered, possibly by the South African security forces, in 1978. Nelson Mandela described Turner "as a source of inspiration".

Cedric Nunn is a South African photographer best known for his photography depicting the country before and after the end of apartheid.

Eric Miller is a professional photographer based in South Africa. Miller was born in Cape Town but spent his childhood in Johannesburg. After studying psychology and working in the corporate world for several years, Miller was driven by the injustices of apartheid to use his hobby, photography, to document opposition to apartheid by becoming a full-time photographer.

Gisèle Wulfsohn was a South African photographer. Wulfsohn was a newspaper, magazine, and freelance photographer specialising on portrait, education, health and gender issues. She was known for documenting various HIV/AIDS awareness campaigns. She died in 2011 from lung cancer.

Dr. Zainab Asvat was a South African anti-apartheid activist. Asvat was trained as a medical doctor, but was politically active most of her life.

Jo Ractliffe is a South African photographer and teacher working in both Cape Town, where she was born, and Johannesburg, South Africa. She is considered among the most influential South African "social photographers."

"Dubul' ibhunu", translated as shoot the Boer, as kill the Boer or as kill the farmer, is a controversial anti-apartheid South African song. It is sung in Xhosa or Zulu. The song originates in the struggle against apartheid when it was first sung to protest the Afrikaner-dominated apartheid government of South Africa.

References

- ↑ "Dutch East India Company Facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Dutch East India Company". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "The arrival of KhoiKhoi | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- 1 2 "Photography and the Liberation Struggle in South Africa | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. 1959-05-31. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "The Edge of Town". Graemewilliams.co.za. Archived from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ Fabian, Johannes (1998). Moments of Freedom: Anthropology and Popular Culture - Johannes Fabian - Google Books. ISBN 9780813917863 . Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Africa Is a Great Country - An FP Slide Show". Foreign Policy. 2013-04-11. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Durban: portrait of an African city". Paulweinberg.co.za. 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "South African Centre for Photography". Photocentre.org.za. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "PPSA : Homepage". Ppsaonline.co.za. Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Photographic Society of South Africa". Pssa.co.za. 2013-08-06. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Photography". Vegaschool.com. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "Stellenbosch Academy of Design and Photography". Stellenboschacademy.co.za. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ↑ "The College of Digital Photography". Codp.co.za. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- Figures and Fictions: Contemporary South African Photography. Göttingen: Steidl; Londýn: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2011. ISBN 9783869302669; ISBN 9783869303062. Fotografie autorů: Jodi Bieber, Kudzanai Chiurai, Hasan and Husain Essop, David Goldblatt, Pieter Hugo, Terry Kurgan, Sabelo Mlangeni, Santu Mofokeng, Zwelethu Mthethwa, Zanele Muholi, Jo Ractliffe, Berni Searle, Mikhael Subotzky, Guy Tillim, Nontsikelelo Veleko, Graeme Williams a Roelof van Wyk.