Pied-piping in English

Wh-clauses vs. relative clauses

Wh-clauses

In English, pied-piping occurs when a wh-expression drags its containing phrase with it to the front of the clause. The pied-piped material can be a noun phrase (NP), an adjective phrase (AP), an adverb phrase (AdvP), or a prepositional phrase (PP).

In the following examples, the focused expression is indicated in bold, and the fronted word/phrase in the (b) and (c) sentences is underlined, with the gap marking its canonical position. The material that has been pied-piped is any underlined material that is not bolded. The (b) sentences show the focused expression pied-piping the target phrase, and the (c) sentences show absence of pied-piping. which is often ungrammatical.

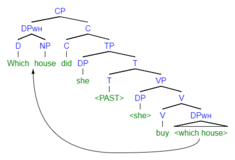

(1) a. She bought that house. b. Which house did she buy ___? c. *Which did she buy ___ house? [6] (2) a. She is ten years old. b. How old is she ___? c. *How is she ___ old?

(3) a. John left the scene very slowly. b. How slowly did John leave the scene ___? c. *How did John leave the scene ___ slowly?

Pied-piping also occurs in embedded wh-clauses:

(4) a. Sarah likes someone's paper. b. Sam asked whose paper Sarah likes ___. c. *Sam asked whose Sarah likes ___ paper.

In (4), the possessive interrogative whose is contained within a determiner phrase (DP) that also includes paper. Attempting to move who and the possessive 's is syntactically impossible without also moving the possessive's complement, paper. As a result, (4b) is grammatical while (4c) is not because the focused expression has moved without the target phrase.

Relative clauses

Pied-piping is very frequent in relative clauses, where a greater flexibility about what can or must be pied-piped is discernible: [7]

(5) a. He likes stories about hobbits. b. ...hobbits stories about whom he likes ___. c. ...hobbits about whom he likes stories ___. d. ...hobbits whom he likes stories about ___.

In English, the pied-piping mechanism is more flexible in relative clauses than in interrogative clauses, because material can be pied-piped that would be less acceptable in the corresponding interrogative clause. [8]

(6) a. She laughed because of the face you made. b. ?Because of what did she laugh ___? - Pied-piping seems marginally acceptable in this matrix wh-clause. c. *We asked because of what she laughed ___? - Pied-piping is simply bad in this embedded wh-clause. d. ...the face you made because of which she laughed ___ - Pied-piping is possible in this relative clause.

(7) a. Tom likes your picture of Susan. b.??Your picture of whom does Tom like ___? - Pied-piping seems strongly marginal in this matrix wh-clause. c. *They know your picture of whom Tom likes ___? - Pied-piping is simply bad in this embedded wh-clause. d. ...Susan, your picture of whom Tom likes ___ - Pied-piping is possible in this relative clause.

The (d) examples, where pied-piping has occurred in a relative clause, are acceptable. The corresponding wh-clauses in the (b) and (c) sentences are much less acceptable. This aspect of pied-piping (i.e. that it is more restricted in wh-clauses than in relative clauses in English) is poorly understood, especially in light of the fact that the same contrast in acceptability does not occur in closely related languages such as German.

Preposition placement variation

Pied-piping vs. preposition stranding

Pied-piping is sometimes optional with English prepositions (in, of, on, to, with, etc.). In these flexible cases, preposition phrases can be constructed with a continuous structure (pied-piping) or an alternative discontinuous structure (preposition stranding). [9] [10] When pied-piping occurs, the preposition phrase is continuous, because the preposition follows the focused expression to a new position. In preposition stranding, the preposition phrase is discontinuous because the preposition stays in its original position while the focused expression moves away.

The following examples show cases where either pied-piping or preposition stranding can occur.

(8) a. Fred spoke with Susan. b. With whom did Fred speak ___. c. Who did Fred speak with ___?

(9) a. Fred is waiting for Susan. b. For whom is Fred waiting ___? c. Who is Fred waiting for ___?

Influences on variation

In cases where pied-piping and preposition stranding are interchangeable, both types of constructions are generally considered acceptable by native English speakers. [11] However, prescriptive grammar rules specify that the object of a preposition must immediately follow its governing preposition. [12] Preposition pied-piping is favoured in formal registers of English, such as academic writing and printed text. [13] In comparison, pied-piping is disfavoured in colloquial registers. Speakers tend to prefer preposition stranding instead of pied-piping in informal contexts, such as private dialogue and private correspondence. [14]

In (8) and (9) above, the (b) sentences present a formal register, while a colloquial register is observed in the (c) sentences.

Obligatory pied-piping

Although flexibility between pied-piping and preposition stranding exists, they are not always interchangeable. Pied-piping is mandatory in some cases. [15] This occurs with some antecedent nouns (e.g., way, extent, point, sense, degree, time, moment) and some prepositions (e.g., beyond, during, underneath). [16]

The following examples show cases where pied-piping is mandatory. [17]

(10) a. You wrote this book in that way. b. I like the way in which you wrote this book ___. c. *I like the way which you wrote this book in ___.

(11) a. There is a field beyond the fence. b. The road ends at the fence, beyond which there is a field ___. c. *The road ends at the fence, which there is a field beyond ___.

Pied-piping is obligatory to form a grammatically sound sentence in the above (b) sentences, while absence of pied-piping results in an ungrammatical sentence in the (c) sentences.

Contrastively, pied-piping is not acceptable in some cases. This typically occurs with prepositions that are part of a verb's meaning. [18] For example, pied-piping is not acceptable for phrasal verbs such as look after and some idioms such as get rid of. [19] In these cases, preposition stranding is obligatory.

The following examples show cases where pied-piping is not acceptable. [20]

(12) a. I'm looking after the cat this weekend. b. This is the cat which I'm looking after ___ this weekend. - Preposition stranding is obligatory c. *This is the cat after which I'm looking ___ this weekend.

(13) a. We have to get rid of the rotten apple. b. Where is the rotten apple which we have to get rid of ___? - Preposition stranding is obligatory c. *Where is the rotten apple of which we have to get rid ___? d. *Where is the rotten apple rid of which we have to get ___?

Pied-piping broadly construed

Broadly construed, pied-piping occurs in other types of discontinuities beyond wh-fronting. If one views just part of a topicalized or extraposed phrase as focused, then pied-piping can be construed as occurring with these other types of discontinuities. Assuming that just the bolded words in these examples bear contrastive focus, the rest of the topicalized or extraposed phrase is pied-piped in each (b) sentence of (14) and (15). Similar examples could be produced for scrambling.

(14) a. She called his parents, not her parents. b. His parents she called, not her parents. - Topicalization can be construed as involving pied-piping.

(15) a. The student whom I know helped, not the student whom you know. b. The student helped whom I know, not the student whom you know. - Extraposition can be construed as involving pied-piping.