The Place de la Concorde is a public square in Paris, France. Measuring 7.6 ha in area, it is the largest square in the French capital. It is located in the city's eighth arrondissement, at the eastern end of the Champs-Élysées.

The Basilica of Sacré Cœur de Montmartre, commonly known as Sacré-Cœur Basilica and often simply Sacré-Cœur, is a Catholic church and minor basilica in Paris dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. It was formally approved as a national historic monument by the National Commission of Patrimony and Architecture on December 8, 2022.

The Jardin du Luxembourg, known in English as the Luxembourg Garden, colloquially referred to as the Jardin du Sénat, is located in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, France. The creation of the garden began in 1612 when Marie de' Medici, the widow of King Henry IV, constructed the Luxembourg Palace as her new residence. The garden today is owned by the French Senate, which meets in the palace. It covers 23 hectares and is known for its lawns, tree-lined promenades, tennis courts, flowerbeds, model sailboats on its octagonal Grand Bassin, as well as picturesque Medici Fountain, built in 1620. The name Luxembourg comes from the Latin Mons Lucotitius, the name of the hill where the garden is located, and locally the garden is informally called "le Luco".

Wallace fountains are public drinking fountains named after, financed by and roughly designed by Sir Richard Wallace. The final design and sculpture is by Wallace's friend Charles-Auguste Lebourg. They are large cast-iron sculptures scattered throughout the city of Paris, France, mainly along the most-frequented sidewalks. A great aesthetic success, they are recognized worldwide as one of the symbols of Paris. A Wallace fountain can be seen outside the Wallace Collection in London, the gallery that houses the works of art collected by Sir Richard Wallace and the first four Marquesses of Hertford.

The Church of Saint-Sulpice is a Catholic church in Paris, France, on the east side of Place Saint-Sulpice, in the 6th arrondissement. Only slightly smaller than Notre-Dame and Saint-Eustache, it is the third largest church in the city. It is dedicated to Sulpitius the Pious. Construction of the present building, the second on the site, began in 1646. During the 18th century, an elaborate gnomon, the Gnomon of Saint-Sulpice, was constructed in the church. Saint-Sulpice is also known for its Great Organ, one of the most significant organs in the world.

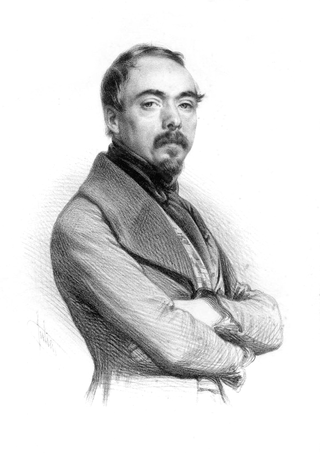

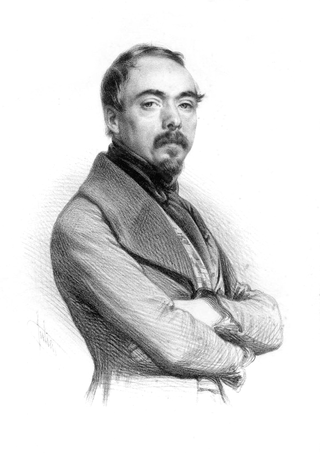

Jean-Antoine-Gabriel Davioud was a French architect. He worked closely with Baron Haussmann on the transformation of Paris under Napoleon III during the Second Empire. Davioud is remembered for his contributions to architecture, parks and urban amenities. These contributions now form an integral part of the style of Haussmann's Paris.

La Fontaine Park is a 34 ha urban park located in the borough of Le Plateau-Mont-Royal in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Named in honour of Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine, The park's features include two linked ponds with a fountain and waterfalls, the Théâtre de Verdure open-air venue, the Calixa-Lavallée cultural centre, a monument to Adam Dollard des Ormeaux, playing fields and tennis courts.

Second Empire style, also known as the Napoleon III style, is a highly eclectic style of architecture and decorative arts originating in the Second French Empire. It was characterized by elements of many different historical styles, and also made innovative use of modern materials, such as iron frameworks and glass skylights. It flourished during the reign of Emperor Napoleon III (1852–1870) and had an important influence on architecture and decoration in the rest of Europe and North America. Major examples of the style include the Opéra Garnier (1862–1871) in Paris by Charles Garnier, the Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art, the Church of Saint Augustine (1860–1871), and the Philadelphia City Hall (1871–1901). The architectural style was closely connected with Haussmann's renovation of Paris carried out during the Second Empire; the new buildings, such as the Opéra, were intended as the focal points of the new boulevards.

Antonin-Marie Moine was a French romantic sculptor in the first half of the 19th century.

The Place des Jacobins is a square located in the 2nd arrondissement of Lyon. It was created in 1556 and a fountain was added in 1856. The square belongs to the zone classified as World Heritage Site by UNESCO. According to Jean Pelletier, this square is one of the most famous in Lyon, because of its location in the center of the 2nd arrondissement and its heavy traffic, as 12 streets lead here. The square, particularly its architecture and its features, has changed its appearance many times throughout years.

The Fountains in Paris originally provided drinking water for city residents, and now are decorative features in the city's squares and parks. Paris has more than two hundred fountains, the oldest dating back to the 16th century. It also has more than one hundred Wallace drinking fountains. Most of the fountains are the property of the municipality.

The Fontaine Saint-Michel is a monumental fountain located in Place Saint-Michel in the 5th arrondissement in Paris. It was constructed in 1858–1860 during the French Second Empire by the architect Gabriel Davioud. It has been listed since 1926 as a monument historique by the French Ministry of Culture.

The Fountain in Piazza Santa Maria in Trastevere is a fountain located in the square in front of the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome, Italy. It is believed to be the oldest fountain in Rome, dating back, according to some sources, to the 8th century. The present fountain is the work of Donato Bramante, with later additions by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Carlo Fontana.

The Fontaine du Palmier (1806-1808) or Fontaine de la Victoire is a monumental fountain located in the Place du Châtelet, between the Théâtre du Châtelet and the Théâtre de la Ville, in the First Arrondissement of Paris. It was designed to provide fresh drinking water to the population of the neighborhood and to commemorate the victories of Napoleon Bonaparte. It is the largest fountain built during Napoleon's reign still in existence. The closest métro station is Châtelet

François-Jean Bralle was a French architect and engineer, best known as for the construction of fountains in Paris during the time of Napoleon Bonaparte. Bralle was commissioned to build fifteen new fountains in Paris, including the fontaine de Mars, the fontaine du Fellah, and the Fontaine du Palmier in the Place du Châtelet, which are still functioning today.

The Fontaine Saint-Sulpice is a monumental fountain located in Place Saint-Sulpice in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. It was constructed between 1843 and 1848 by the architect Louis Visconti, who also designed the tomb of Napoleon.

The Fontaine Molière is a fountain in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, at the junction of the Rue Molière and the Rue de Richelieu.

The Rue Bonaparte is a street in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. It spans the Quai Voltaire/Quai Malaquais to the Jardin du Luxembourg, crossing the Place Saint-Germain-des-Prés and the Place Saint-Sulpice and has housed many of France's most famous names and institutions as well as other well-known figures from abroad.

The city of Paris has notable examples of architecture from the Middle Ages to the 21st century. It was the birthplace of the Gothic style, and has important monuments of the French Renaissance, Classical revival, the Flamboyant style of the reign of Napoleon III, the Belle Époque, and the Art Nouveau style. The great Exposition Universelle (1889) and 1900 added Paris landmarks, including the Eiffel Tower and Grand Palais. In the 20th century, the Art Deco style of architecture first appeared in Paris, and Paris architects also influenced the postmodern architecture of the second half of the century.