Related Research Articles

Ferromagnetism is the basic mechanism by which certain materials form permanent magnets, or are attracted to magnets. In physics, several different types of magnetism are distinguished. Ferromagnetism is the strongest type and is responsible for the common phenomenon of magnetism in magnets encountered in everyday life. Substances respond weakly to magnetic fields with three other types of magnetism—paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and antiferromagnetism—but the forces are usually so weak that they can be detected only by sensitive instruments in a laboratory. An everyday example of ferromagnetism is a refrigerator magnet used to hold notes on a refrigerator door. The attraction between a magnet and ferromagnetic material is "the quality of magnetism first apparent to the ancient world, and to us today".

The Hall effect is the production of a voltage difference across an electrical conductor that is transverse to an electric current in the conductor and to an applied magnetic field perpendicular to the current. It was discovered by Edwin Hall in 1879.

Magnetism is a class of physical attributes that are mediated by magnetic fields. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, which acts on other currents and magnetic moments. Magnetism is one aspect of the combined phenomenon of electromagnetism. The most familiar effects occur in ferromagnetic materials, which are strongly attracted by magnetic fields and can be magnetized to become permanent magnets, producing magnetic fields themselves. Demagnetizing a magnet is also possible. Only a few substances are ferromagnetic; the most common ones are iron, cobalt and nickel and their alloys. The rare-earth metals neodymium and samarium are less common examples. The prefix ferro- refers to iron, because permanent magnetism was first observed in lodestone, a form of natural iron ore called magnetite, Fe3O4.

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the magnetic field. A permanent magnet's magnetic field pulls on ferromagnetic materials such as iron, and attracts or repels other magnets. In addition, a magnetic field that varies with location will exert a force on a range of non-magnetic materials by affecting the motion of their outer atomic electrons. Magnetic fields surround magnetized materials, and are created by electric currents such as those used in electromagnets, and by electric fields varying in time. Since both strength and direction of a magnetic field may vary with location, it is described mathematically by a function assigning a vector to each point of space, called a vector field.

Magnetoresistance is the tendency of a material to change the value of its electrical resistance in an externally-applied magnetic field. There are a variety of effects that can be called magnetoresistance. Some occur in bulk non-magnetic metals and semiconductors, such as geometrical magnetoresistance, Shubnikov–de Haas oscillations, or the common positive magnetoresistance in metals. Other effects occur in magnetic metals, such as negative magnetoresistance in ferromagnets or anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR). Finally, in multicomponent or multilayer systems, giant magnetoresistance (GMR), tunnel magnetoresistance (TMR), colossal magnetoresistance (CMR), and extraordinary magnetoresistance (EMR) can be observed.

Spintronics, also known as spin electronics, is the study of the intrinsic spin of the electron and its associated magnetic moment, in addition to its fundamental electronic charge, in solid-state devices. The field of spintronics concerns spin-charge coupling in metallic systems; the analogous effects in insulators fall into the field of multiferroics.

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Some magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, one that measures the direction of an ambient magnetic field, in this case, the Earth's magnetic field. Other magnetometers measure the magnetic dipole moment of a magnetic material such as a ferromagnet, for example by recording the effect of this magnetic dipole on the induced current in a coil.

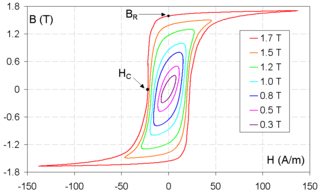

Hysteresis is the dependence of the state of a system on its history. For example, a magnet may have more than one possible magnetic moment in a given magnetic field, depending on how the field changed in the past. Plots of a single component of the moment often form a loop or hysteresis curve, where there are different values of one variable depending on the direction of change of another variable. This history dependence is the basis of memory in a hard disk drive and the remanence that retains a record of the Earth's magnetic field magnitude in the past. Hysteresis occurs in ferromagnetic and ferroelectric materials, as well as in the deformation of rubber bands and shape-memory alloys and many other natural phenomena. In natural systems it is often associated with irreversible thermodynamic change such as phase transitions and with internal friction; and dissipation is a common side effect.

In physics and materials science, the Curie temperature (TC), or Curie point, is the temperature above which certain materials lose their permanent magnetic properties, which can be replaced by induced magnetism. The Curie temperature is named after Pierre Curie, who showed that magnetism was lost at a critical temperature.

In electromagnetism, the magnetic susceptibility is a measure of how much a material will become magnetized in an applied magnetic field. It is the ratio of magnetization M to the applied magnetizing field intensity H. This allows a simple classification, into two categories, of most materials' responses to an applied magnetic field: an alignment with the magnetic field, χ > 0, called paramagnetism, or an alignment against the field, χ < 0, called diamagnetism.

Coercivity, also called the magnetic coercivity, coercive field or coercive force, is a measure of the ability of a ferromagnetic material to withstand an external magnetic field without becoming demagnetized. Coercivity is usually measured in oersted or ampere/meter units and is denoted HC.

In physics, a ferromagnetic material is said to have magnetocrystalline anisotropy if it takes more energy to magnetize it in certain directions than in others. These directions are usually related to the principal axes of its crystal lattice. It is a special case of magnetic anisotropy.

A Halbach array is a special arrangement of permanent magnets that augments the magnetic field on one side of the array while cancelling the field to near zero on the other side. This is achieved by having a spatially rotating pattern of magnetisation.

Giant magnetoresistance (GMR) is a quantum mechanical magnetoresistance effect observed in multilayers composed of alternating ferromagnetic and non-magnetic conductive layers. The 2007 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Albert Fert and Peter Grünberg for the discovery of GMR.

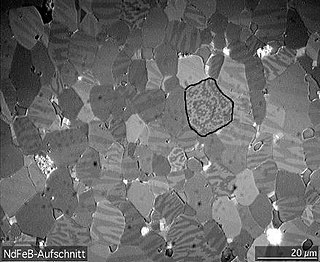

A magnetic domain is a region within a magnetic material in which the magnetization is in a uniform direction. This means that the individual magnetic moments of the atoms are aligned with one another and they point in the same direction. When cooled below a temperature called the Curie temperature, the magnetization of a piece of ferromagnetic material spontaneously divides into many small regions called magnetic domains. The magnetization within each domain points in a uniform direction, but the magnetization of different domains may point in different directions. Magnetic domain structure is responsible for the magnetic behavior of ferromagnetic materials like iron, nickel, cobalt and their alloys, and ferrimagnetic materials like ferrite. This includes the formation of permanent magnets and the attraction of ferromagnetic materials to a magnetic field. The regions separating magnetic domains are called domain walls, where the magnetization rotates coherently from the direction in one domain to that in the next domain. The study of magnetic domains is called micromagnetics.

Magnetic immunoassay (MIA) is a type of diagnostic immunoassay using magnetic beads as labels in lieu of conventional enzymes (ELISA), radioisotopes (RIA) or fluorescent moieties to detect a specified analyte. MIA involves the specific binding of an antibody to its antigen, where a magnetic label is conjugated to one element of the pair. The presence of magnetic beads is then detected by a magnetic reader (magnetometer) which measures the magnetic field change induced by the beads. The signal measured by the magnetometer is proportional to the analyte concentration in the initial sample.

The inverse magnetostrictive effect, magnetoelastic effect or Villari effect is the change of the magnetic susceptibility of a material when subjected to a mechanical stress.

The Stoner–Wohlfarth model is a widely used model for the magnetization of single-domain ferromagnets. It is a simple example of magnetic hysteresis and is useful for modeling small magnetic particles in magnetic storage, biomagnetism, rock magnetism and paleomagnetism.

The demagnetizing field, also called the stray field, is the magnetic field (H-field) generated by the magnetization in a magnet. The total magnetic field in a region containing magnets is the sum of the demagnetizing fields of the magnets and the magnetic field due to any free currents or displacement currents. The term demagnetizing field reflects its tendency to act on the magnetization so as to reduce the total magnetic moment. It gives rise to shape anisotropy in ferromagnets with a single magnetic domain and to magnetic domains in larger ferromagnets.

The magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy of a ferromagnetic crystal can be expressed as a power series of direction cosines of the magnetic moment with respect to the crystal axes. The coefficient of those terms are the anisotropy constant. In general the expansion is limited to few terms. Normally the magnetization curve is continuous respect to applied field up to saturation but, in certain intervals of the anisotropy constant values, irreversible field induced rotations of the magnetization are possible implying first order magnetization transition between equivalent magnetization minima, the so-called first order magnetization process (FOMP).

References

- 1 2 Planar Hall sensor for influenza immunoassay

- ↑ American Physical Society

- ↑ Science Direct [ dead link ]

- ↑ Applied Physics Letters

- ↑ Science Direct [ dead link ]

- ↑ Science Direct 2F1995&_alid=519937647&_rdoc=1&_fmt=summary&_orig=search&_cdi=4996&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=c5fd21474ce60d55a16eb84cac97a155