A comic strip is a sequence of drawings, often cartoons, arranged in interrelated panels to display brief humor or form a narrative, often serialized, with text in balloons and captions. Traditionally, throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, these have been published in newspapers and magazines, with daily horizontal strips printed in black-and-white in newspapers, while Sunday papers offered longer sequences in special color comics sections. With the advent of the internet, online comic strips began to appear as webcomics.

A cartoon is a type of visual art that is typically drawn, frequently animated, in an unrealistic or semi-realistic style. The specific meaning has evolved over time, but the modern usage usually refers to either: an image or series of images intended for satire, caricature, or humor; or a motion picture that relies on a sequence of illustrations for its animation. Someone who creates cartoons in the first sense is called a cartoonist, and in the second sense they are usually called an animator.

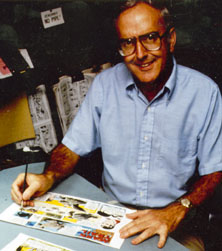

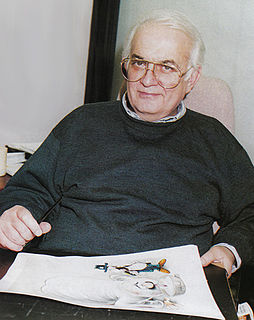

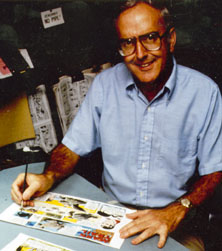

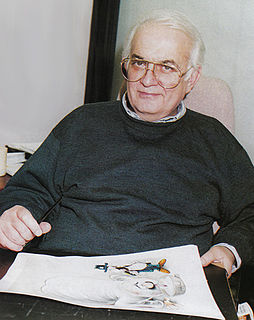

A cartoonist is a visual artist who specializes in both drawing and writing cartoons or comics. Cartoonists differ from comic writers, comic book artists, or comic book illustrators in that they produce both the literary and graphic components of the work as part of their practice. Cartoonists may work in a variety of formats, including booklets, comic strips, comic books, editorial cartoons, graphic novels, manuals, gag cartoons, storyboards, posters, shirts, books, advertisements, greeting cards, magazines, newspapers, webcomics, and video game packaging.

An editorial cartoonist, also known as a political cartoonist, is an artist who draws editorial cartoons that contain some level of political or social commentary. Their cartoons are used to convey and question an aspect of daily news or current affairs in a national or international context. Political cartoonists generally adopt a caricaturist style of drawing, to capture the likeness of a politician or subject. They may also employ humor or satire to ridicule an individual or group, emphasize their point of view or comment on a particular event.

Carlos Latuff is a Brazilian political cartoonist. His work deals with themes such as anti-Western sentiment, anti-capitalism, and opposition to U.S. military intervention. He is best known for his images depicting the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the Arab Spring events.

Al-Ahram, founded on 5 August 1875, is the most widely circulating Egyptian daily newspaper, and the second oldest after al-Waqa'i`al-Masriya. It is majority owned by the Egyptian government, and is considered a newspaper of record for Egypt.

Charlie Hebdo is a French satirical weekly magazine, featuring cartoons, reports, polemics, and jokes. Stridently non-conformist in tone, the publication has been described as anti-racist, sceptical, secular, and within the tradition of left-wing radicalism, publishing articles about the far-right, religion, politics and culture.

Milt Gross was an American cartoonist and animator. His work is noted for its exaggerated cartoon style and Yiddish-inflected English dialogue. He originated the non-sequitur "Banana Oil!" as a phrase deflating pomposity and posing. His character Count Screwloose's admonition, "Iggy, keep an eye on me!", became a national catchphrase. The National Cartoonists Society fund to aid indigent cartoonists and their families for many years was known as the Milt Gross Fund. In 2005, it was absorbed by the Society's Foundation, which continues the charitable work of the Fund.

The Eastern Color Printing Company was a company that published comic books, beginning in 1933. At first, it was only newspaper comic strip reprints, but later on, original material was published. Eastern Color Printing was incorporated in 1928, and soon became successful by printing color newspaper sections for several New England and New York papers. Eastern is most notable for its production of Funnies on Parade and Famous Funnies, two publications that gave birth to the American comic book industry.

The Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy began after the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published 12 editorial cartoons on 30 September 2005, most of which depicted Muhammad, a principal figure of the religion of Islam. The newspaper announced that this was an attempt to contribute to the debate about criticism of Islam and self-censorship. Muslim groups in Denmark complained, and the issue eventually led to protests around the world, including violence and riots in some Muslim countries.

Georges David Wolinski was a French cartoonist and comics writer. He was killed on 7 January 2015 in a terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo along with other staff.

Ali Farzat or Ali Ferzat is a Syrian political cartoonist. He has published more than 15,000 caricatures in Syrian, Arab and international newspapers. He serves as the head of the Arab Cartoonists Association. In 2011, he received Sakharov Prize for peace. Farzat was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine in 2012.

Canadian comics refers to comics and cartooning by citizens of Canada or permanent residents of Canada regardless of residence. Canada has two official languages, and distinct comics cultures have developed in English and French Canada. The English tends to follow American trends, and the French, Franco-Belgian ones, with little crossover between the two cultures. Canadian comics run the gamut of comics forms, including editorial cartooning, comic strips, comic books, graphic novels, and webcomics, and are published in newspapers, magazines, books, and online. They have received attention in international comics communities and have received support from the federal and provincial governments, including grants from the Canada Council for the Arts. There are comics publishers throughout the country, as well as large small press, self-publishing, and minicomics communities.

The media of Bahrain mainly consists of several weekly and daily newspapers, with the Information Affairs Authority controlling Bahrain's state-owned Bahrain Radio and Television Corporation, which broadcasts radio and television services. The media is predominantly in Arabic though English language and Malayalam newspapers are beginning to emerge in the country. The IAA also controls the Bahrain News Agency which monitors, originates and relays national and international news in Arabic and English, usually generating from 90 to 150 stories a day. Bahrain Telecommunication Company, trading as Batelco, is Bahrain's sole Internet service provider. In 2015, there were an estimated 1.29 million internet user, a penetration of 96.4%.

Mahmoud Kahilمحمود كحيل was a Lebanese-born British editorial cartoonist.

In a country that has not enjoyed complete freedom of speech; political satire in Jordan has been a way to criticize and make claims on the political authorities. Be it expressed in press as in weekly satirical newspapers, cartoons, prose, or as in recent times, on online social media platforms, satire in Jordan represents a unique genre that has reflected a local mode and attitude towards local and global issues. While it is not meant entirely to entertain, political satire in Jordan has been used as a way to poke fun at elected governments and their failure to tend to local issues. Like satirists worldwide, the Jordanian satirists aim to use pun and indirect references to tackle taboos, defy the restrictive laws that inhibit the freedom of speech, and convey public grievances.

Nadia Khiari is a Tunisian cartoonist, painter, graffiti artist and art teacher. She is best known for her chronicles and cartoon collections about the Arab Springs, particularly for her character 'Willis from Tunis', dubbed the "Cat of the Revolution" in some sources.