Example

An example of a categorical polysyllogism is:

- All good students will readily understand polysyllogisms

- All students of logic are good students

- Therefore, all students of logic will readily understand polysyllogisms

- But all people who read this web page are students of logic

- Therefore, all people who read this web page will readily understand polysyllogisms

This argument has the following structure:

- All A is B

- All C is A

- Therefore: all C is B

- All D is C

- Therefore, all D is B

Note two points: first, the makeup of a polysyllogism need not be limited to two component syllogisms. In fact, it can have any number of component syllogisms. Second, validity depends on all its parts. If any one is not valid then the whole polysyllogism is to be considered invalid. [2]

An example for a propositional polysyllogism is:

- It is raining.

- If we go out while it is raining we will get wet.

- If we get wet, we will get cold.

- Therefore, if we go out we will get cold.

Examination of the structure of the argument reveals the following sequence of constituent (pro)syllogisms:

- It is raining.

- If we go out while it is raining we will get wet.

- Therefore, if we go out we will get wet.

- If we go out we will get wet.

- If we get wet, we will get cold.

- Therefore, if we go out we will get cold.

In classical logic, disjunctive syllogism is a valid argument form which is a syllogism having a disjunctive statement for one of its premises.

A false dilemma, also referred to as false dichotomy or false binary, is an informal fallacy based on a premise that erroneously limits what options are available. The source of the fallacy lies not in an invalid form of inference but in a false premise. This premise has the form of a disjunctive claim: it asserts that one among a number of alternatives must be true. This disjunction is problematic because it oversimplifies the choice by excluding viable alternatives, presenting the viewer with only two absolute choices when, in fact, there could be many.

In propositional logic, modus ponens, also known as modus ponendo ponens, implication elimination, or affirming the antecedent, is a deductive argument form and rule of inference. It can be summarized as "P implies Q.P is true. Therefore, Q must also be true."

In propositional logic, modus tollens (MT), also known as modus tollendo tollens and denying the consequent, is a deductive argument form and a rule of inference. Modus tollens is a mixed hypothetical syllogism that takes the form of "If P, then Q. Not Q. Therefore, not P." It is an application of the general truth that if a statement is true, then so is its contrapositive. The form shows that inference from P implies Q to the negation of Q implies the negation of P is a valid argument.

A syllogism is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

Deductive reasoning is the process of drawing valid inferences. An inference is valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, meaning that it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false.

In classical logic, a hypothetical syllogism is a valid argument form, a deductive syllogism with a conditional statement for one or both of its premises. Ancient references point to the works of Theophrastus and Eudemus for the first investigation of this kind of syllogisms.

The sorites paradox is a paradox that results from vague predicates. A typical formulation involves a heap of sand, from which grains are removed individually. With the assumption that removing a single grain does not cause a heap to not be considered a heap anymore, the paradox is to consider what happens when the process is repeated enough times that only one grain remains: is it still a heap? If not, when did it change from a heap to a non-heap?

Inferences are steps in reasoning, moving from premises to logical consequences; etymologically, the word infer means to "carry forward". Inference is theoretically traditionally divided into deduction and induction, a distinction that in Europe dates at least to Aristotle. Deduction is inference deriving logical conclusions from premises known or assumed to be true, with the laws of valid inference being studied in logic. Induction is inference from particular evidence to a universal conclusion. A third type of inference is sometimes distinguished, notably by Charles Sanders Peirce, contradistinguishing abduction from induction.

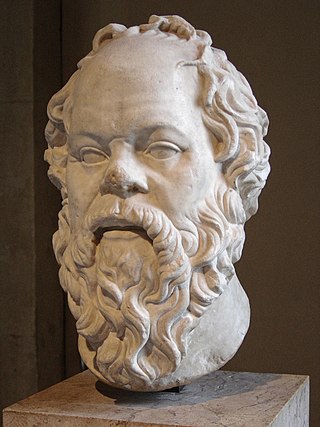

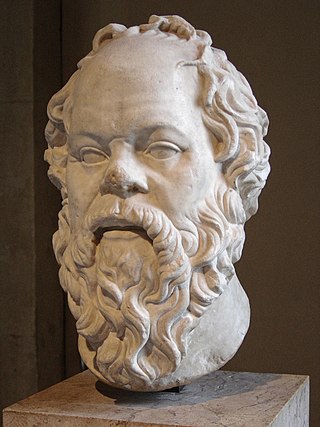

In logic and formal semantics, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly by his followers, the Peripatetics. It was revived after the third century CE by Porphyry's Isagoge.

The fallacy of the undistributed middle is a formal fallacy that is committed when the middle term in a categorical syllogism is not distributed in either the minor premise or the major premise. It is thus a syllogistic fallacy.

The fallacy of exclusive premises is a syllogistic fallacy committed in a categorical syllogism that is invalid because both of its premises are negative.

A false premise is an incorrect proposition that forms the basis of an argument or syllogism. Since the premise is not correct, the conclusion drawn may be in error. However, the logical validity of an argument is a function of its internal consistency, not the truth value of its premises.

In philosophical logic, the masked-man fallacy is committed when one makes an illicit use of Leibniz's law in an argument. Leibniz's law states that if A and B are the same object, then A and B are indiscernible. By modus tollens, this means that if one object has a certain property, while another object does not have the same property, the two objects cannot be identical. The fallacy is "epistemic" because it posits an immediate identity between a subject's knowledge of an object with the object itself, failing to recognize that Leibniz's Law is not capable of accounting for intensional contexts.

In logic and philosophy, a formal fallacy, deductive fallacy, logical fallacy or non sequitur is a pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure that can neatly be expressed in a standard logic system, for example propositional logic. It is defined as a deductive argument that is invalid. The argument itself could have true premises, but still have a false conclusion. Thus, a formal fallacy is a fallacy in which deduction goes wrong, and is no longer a logical process. This may not affect the truth of the conclusion, since validity and truth are separate in formal logic.

In Aristotelian logic, Baralipton is a mnemonic word used to identify a form of syllogism. Specifically, the first two propositions are universal affirmative (A), and the third (conclusion) particular affirmative (I)-- hence BARALIPTON. The argument is also in the First Figure, and therefore would be found in the first portion of the full mnemonic poem as formulated by William of Sherwood; later this syllogism came to be considered one of the Fourth Figure.

Logic is the formal science of using reason and is considered a branch of both philosophy and mathematics and to a lesser extent computer science. Logic investigates and classifies the structure of statements and arguments, both through the study of formal systems of inference and the study of arguments in natural language. The scope of logic can therefore be very large, ranging from core topics such as the study of fallacies and paradoxes, to specialized analyses of reasoning such as probability, correct reasoning, and arguments involving causality. One of the aims of logic is to identify the correct and incorrect inferences. Logicians study the criteria for the evaluation of arguments.

In logic, reductio ad absurdum, also known as argumentum ad absurdum or apagogical arguments, is the form of argument that attempts to establish a claim by showing that the opposite scenario would lead to absurdity or contradiction.

Stoic logic is the system of propositional logic developed by the Stoic philosophers in ancient Greece.