Related Research Articles

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, properties, behavior and the changes they undergo during reactions with other substances. Chemistry also addresses the nature of chemical bonds in chemical compounds.

A chemical element is a chemical substance that cannot be broken down into other substances by chemical reactions. The basic particle that constitutes a chemical element is the atom. Chemical elements are identified by the number of protons in the nuclei of their atoms, known as the element's atomic number. For example, oxygen has an atomic number of 8, meaning that each oxygen atom has 8 protons in its nucleus. Two or more atoms of the same element can combine to form molecules, in contrast to chemical compounds or mixtures, which contain atoms of different elements. Atoms can be transformed into different elements in nuclear reactions, which can change an atom's atomic number.

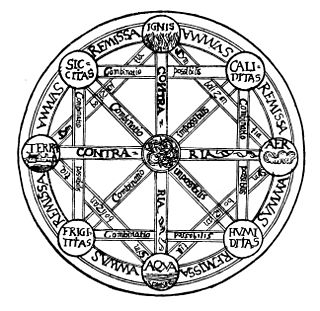

The classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Tibet, and India had similar lists which sometimes referred, in local languages, to "air" as "wind" and the fifth element as "void".

A metal is a material that, when freshly prepared, polished, or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. Metals are typically ductile and malleable. These properties are the result of the metallic bond between the atoms or molecules of the metal.

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek φλογιστόνphlogistón, from φλόξphlóx (flame). The idea was first proposed in 1667 by Johann Joachim Becher and later put together more formally by Georg Ernst Stahl. Phlogiston theory attempted to explain chemical processes such as combustion and rusting, now collectively known as oxidation. It was challenged by the concomitant weight increase and was abandoned before the end of the 18th century following experiments by Antoine Lavoisier and others. Phlogiston theory led to experiments that ultimately concluded with the discovery of oxygen.

Carl Wilhelm Scheele was a Swedish German pharmaceutical chemist.

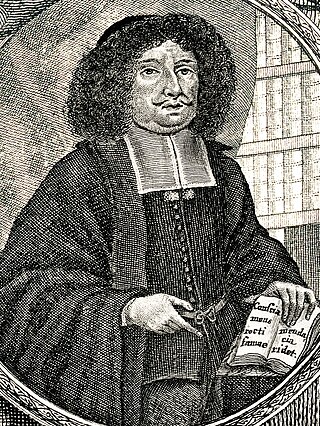

Georg Ernst Stahl was a German chemist, physician and philosopher. He was a supporter of vitalism, and until the late 18th century his works on phlogiston were accepted as an explanation for chemical processes.

A period 3 element is one of the chemical elements in the third row of the periodic table of the chemical elements. The periodic table is laid out in rows to illustrate recurring (periodic) trends in the chemical behavior of the elements as their atomic number increases: a new row is begun when chemical behavior begins to repeat, meaning that elements with similar behavior fall into the same vertical columns. The third period contains eight elements: sodium, magnesium, aluminium, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur, chlorine and argon. The first two, sodium and magnesium, are members of the s-block of the periodic table, while the others are members of the p-block. All of the period 3 elements occur in nature and have at least one stable isotope.

In Renaissance alchemy, alkahest was the theorized "universal solvent". It was supposed to be capable of dissolving any other substance, including gold, without altering or destroying its fundamental components.

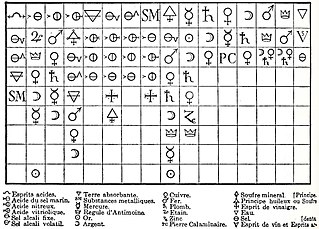

Alchemical symbols, originally devised as part of alchemy, were used to denote some elements and some compounds until the 18th century. Although notation was partly standardized, style and symbol varied between alchemists. Lüdy-Tenger published an inventory of 3,695 symbols and variants, and that was not exhaustive, omitting for example many of the symbols used by Isaac Newton. This page therefore lists only the most common symbols.

The periodic table is an arrangement of the chemical elements, structured by their atomic number, electron configuration and recurring chemical properties. In the basic form, elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, in the reading sequence. Then, rows and columns are created by starting new rows and inserting blank cells, so that rows (periods) and columns (groups) show elements with recurring properties. For example, all elements in group (column) 18 are noble gases that are largely—though not completely—unreactive.

In chemistry, a trivial name is a non-systematic name for a chemical substance. That is, the name is not recognized according to the rules of any formal system of chemical nomenclature such as IUPAC inorganic or IUPAC organic nomenclature. A trivial name is not a formal name and is usually a common name.

The history of chemistry represents a time span from ancient history to the present. By 1000 BC, civilizations used technologies that would eventually form the basis of the various branches of chemistry. Examples include the discovery of fire, extracting metals from ores, making pottery and glazes, fermenting beer and wine, extracting chemicals from plants for medicine and perfume, rendering fat into soap, making glass, and making alloys like bronze.

Iatrochemistry is an archaic pre-scientific school of thought that was supplanted by modern chemistry and medicine. Having its roots in alchemy, iatrochemistry sought to provide chemical solutions to diseases and medical ailments.

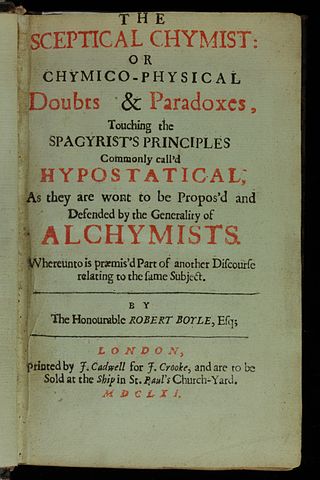

The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes is the title of a book by Robert Boyle, published in London in 1661. In the form of a dialogue, the Sceptical Chymist presented Boyle's hypothesis that matter consisted of corpuscles and clusters of corpuscles in motion and that every phenomenon was the result of collisions of particles in motion. Boyle also objected to the definitions of elemental bodies propounded by Aristotle and by Paracelsus, instead defining elements as "perfectly unmingled bodies". For these reasons Robert Boyle has sometimes been called the founder of modern chemistry.

In the history of chemistry, the chemical revolution, also called the first chemical revolution, was the reformulation of chemistry during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which culminated in the law of conservation of mass and the oxygen theory of combustion.

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Chemical substances can be simple substances, chemical compounds, or alloys.

This glossary of chemistry terms is a list of terms and definitions relevant to chemistry, including chemical laws, diagrams and formulae, laboratory tools, glassware, and equipment. Chemistry is a physical science concerned with the composition, structure, and properties of matter, as well as the changes it undergoes during chemical reactions; it features an extensive vocabulary and a significant amount of jargon.

A chemical compound is a chemical substance composed of many identical molecules containing atoms from more than one chemical element held together by chemical bonds. A molecule consisting of atoms of only one element is therefore not a compound. A compound can be transformed into a different substance by a chemical reaction, which may involve interactions with other substances. In this process, bonds between atoms may be broken and/or new bonds formed.

Paul of Taranto was a 13th-century Franciscan alchemist and author from southern Italy. Perhaps the best known of his works is his Theorica et practica, which defends alchemical principles by describing the theoretical and practical reasoning behind it. It has also been argued that Paul is the author of the much more widely known alchemical text Summa perfectionis, generally attributed to the spurious Jabir, or Pseudo-Geber.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Georg Ernst Stahl (1730) Philosophical Principles of Universal Chemistry, Peter Shaw translator, from Open Library

- 1 2 3 Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent & Isabelle Stengers (1996) A History of Chemistry, Deborah van Dam translator, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-39659-6