Patricia Monique Soltysik was an American woman who was best known as a co-founder and activist in the Symbionese Liberation Army, a far-left militant group based in Berkeley and Oakland, California. She participated in the group's violent activities, including armed bank robbery.

The United Federated Forces of the Symbionese Liberation Army was a small, American militant far-left organization active between 1973 and 1975; it claimed to be a vanguard movement. The FBI and wider American law enforcement considered the SLA to be the first terrorist organization to rise from the American left. Six members died in a May 1974 shootout with police in Los Angeles. The three surviving fugitives recruited new members, but nearly all of them were apprehended in 1975 and prosecuted.

The Black Cultural Association (BCA) was an African-American inmate group founded in 1968 at the California Medical Facility at Vacaville, a California state prison, and formally recognized by prison officials in 1969. The primary purpose of the BCA was to provide educational tutoring to inmates, which it did in conjunction with graduate college students from the nearby San Francisco Bay Area. Outsiders were allowed to attend meetings of the BCA, and tutors provided remedial and advanced courses in mathematics, reading, writing, art, history, political science, and sociology. In time, radical political organizations such as Venceremos infiltrated the BCA, giving rise to BCA factions such as Unisight, which eventually gave birth to the Symbionese Liberation Army.

Donald David DeFreeze, also known as Cinque Mtume and using the nom de guerre "General Field Marshal Cinque", was an American man involved with the far-left radical group Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) and convicted criminal.

Wendy Masako Yoshimura is an American still life watercolor painter. She was a member of the leftist terrorist group the Symbionese Liberation Army during the mid-1970s. She was born in Manzanar, one of numerous World War II-era internment camps for Japanese Americans who were forced out of their homes and businesses along the West Coast. She was raised both in Japan and California's Central Valley.

Venceremos was an American far-left and primarily Chicano political group active in the Palo Alto, California area from 1969 to 1973.

The rights of civilian and military prisoners are governed by both national and international law. International conventions include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the United Nations' Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Emily Harris was, along with her husband William Harris (1945–), a member of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), an American left-wing terrorist group involved in murder, kidnapping, and bank robberies. In the 1970s, she was convicted of kidnapping Patty Hearst.

Kuwasi Balagoon, born Donald Weems, was an American political activist, anarchist and member of the Black Panther Party and Black Liberation Army. Radicalised by race riots in his home state of Maryland growing up, as well as by his experiences while serving in the US Army, Weems became the black nationalist known as Kuwasi Balagoon in New York City in the late 1960s. First becoming involved in local Afrocentric organisations in Harlem, Balagoon would move on to become involved in the New York chapter of the Black Panther Party, which quickly saw him charged and arrested for criminal behaviour. Balagoon was initially part of the Panther 21 case, in which 21 panthers were accused of planning to bomb several locations in New York City, but although the Panther 21 were later acquitted, Balagoon's case was separated off and he was convicted of a New Jersey bank robbery.

A prison strike is an inmate strike or work stoppage that occurs inside a prison, generally to protest poor conditions or low wages for penal labor. Prison strikes may also include hunger strikes.

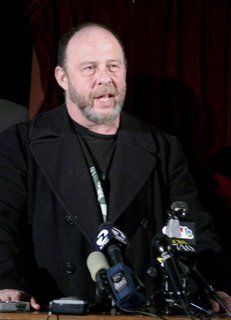

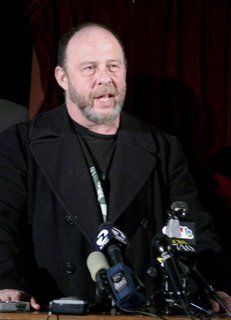

Stuart Hanlon is an attorney based in San Francisco, California who represented San Francisco Police Chief Greg Suhr, Geronimo Pratt and members of the Symbionese Liberation Army.

Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners' Labor Union, 433 U.S. 119 (1977), was a United States Supreme Court case where the court held that prison inmates do not have a right under the First Amendment to join labor unions.

Penal labor in the United States is the practice of using incarcerated individuals to perform various types of work, either for government-run or private industries. Inmates typically engage in tasks such as manufacturing goods, providing services, or working in maintenance roles within prisons. Prison labor is legal under the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime.

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was active in the anti-lynching, movements for civil rights, and prominently participated in the defense and legal appeals in the cause célèbre of the Scottsboro Boys in the early 1930s. Its work contributed to the appeal of the Communist Party among African Americans in the South. In addition to fundraising for defense and assisting in defense strategies, from January 1926 it published Labor Defender, a monthly illustrated magazine that achieved wide circulation. In 1946 the ILD was merged with the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties to form the Civil Rights Congress, which served as the new legal defense organization of the Communist Party USA. It intended to expand its appeal, especially to African Americans in the South. In several prominent cases in which blacks had been sentenced to death in the South, the CRC campaigned on behalf of black defendants. It had some conflict with former allies, such as the NAACP, and became increasingly isolated. Because of federal government pressure against organizations it considered subversive, such as the CRC, it became less useful in representing defendants in criminal justice cases. The CRC was dissolved in 1956. At the same time, in this period, black leaders were expanding the activities and reach of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1954, in a case managed by the NAACP, the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional.

James William Kilgore is a convicted American felon and former fugitive for his activities in the 1970s with the Symbionese Liberation Army, a left-wing terrorist organization in California. After years of research and writing, he later became a research scholar and ultimately worked at the University of Illinois' Center for African Studies in Champaign–Urbana.

Thero Lavon Wheeler (1945–2009), aka Bruce Bradley while a fugitive (1973–1975), was a founding member of the Symbionese Liberation Army, an American left-wing organization in the San Francisco Bay area. He left the group in October 1973 as he objected to its plans to undertake violent acts. Law enforcement later classified the SLA as a terrorist group.

Mary Alice Siem was a student at the University of California, Berkeley when she became involved in 1973 with a prisoner outreach program at Vacaville Prison. She became the girlfriend of Thero Wheeler, an inmate who escaped in August 1973. He was a founding member of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), an extremist group based in Oakland that was classified as terrorist by law enforcement. It was known for murders, armed robberies and the kidnapping of heiress Patty Hearst after Wheeler and Siem left the group in October 1973.

Joseph Michael Remiro is an American convicted murderer and one of the founding members of the Symbionese Liberation Army in the early fall of 1973. It was an American leftist terrorist group based in the Bay Area of California. He used the pseudonym or nom de guerre "Bo" while he was a member of the group.

Colston Richard Westbrook was an American teacher and linguist who worked in the fields of minority education and literacy. At the University of California, Berkeley, he established a program of prison outreach and approved students from the Bay Area to serve as volunteers. Some of the participants from Berkeley and two former prisoners at Vacaville Prison were among the founding members in 1973 of the radical leftist group known as the Symbionese Liberation Army.

The 1970Folsom Prison strike was a significant event for U.S. prison reform and protest. During the strike, over 2,400 incarcerated individuals at Folsom State Prison in Folsom, California, initiated a work stoppage and hunger strike. The strike began on November 3, 1970, and lasted 19 days. The strike was organized to address various grievances, including racial discrimination, inadequate medical care, overcrowding and labor conditions. Prisoners from different backgrounds, including members of the Black Panther Party and Brown Berets, participated, helping the strike gain attention nationwide. The strike was declared the day prior to the 1970 California gubernatorial election, increasing public and political attention to the demands.