Related Research Articles

Anatomy is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its beginnings in prehistoric times. Anatomy is inherently tied to developmental biology, embryology, comparative anatomy, evolutionary biology, and phylogeny, as these are the processes by which anatomy is generated, both over immediate and long-term timescales. Anatomy and physiology, which study the structure and function of organisms and their parts respectively, make a natural pair of related disciplines, and are often studied together. Human anatomy is one of the essential basic sciences that are applied in medicine, and is often studied alongside physiology.

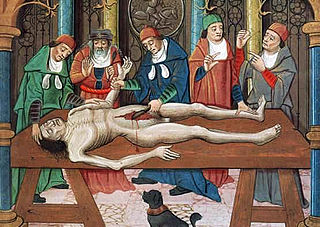

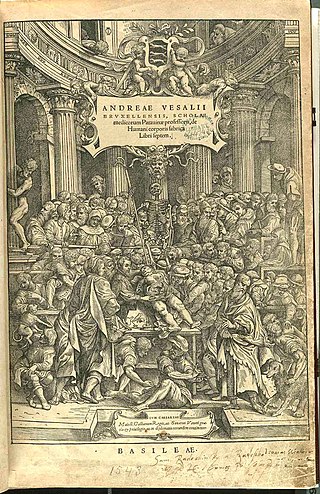

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of sacrificial victims to the sophisticated analyses of the body performed by modern anatomists and scientists. Written descriptions of human organs and parts can be traced back thousands of years to ancient Egyptian papyri, where attention to the body was necessitated by their highly elaborate burial practices.

The pyloruspyloric region or pyloric part connects the stomach to the duodenum. The pylorus is considered as having two parts, the pyloric antrum and the pyloric canal. The pyloric canal ends as the pyloric orifice, which marks the junction between the stomach and the duodenum. The orifice is surrounded by a sphincter, a band of muscle, called the pyloric sphincter. The word pylorus comes from Greek πυλωρός, via Latin. The word pylorus in Greek means "gatekeeper", related to "gate" and is thus linguistically related to the word "pylon".

Dissection is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of death in humans. Less extensive dissection of plants and smaller animals preserved in a formaldehyde solution is typically carried out or demonstrated in biology and natural science classes in middle school and high school, while extensive dissections of cadavers of adults and children, both fresh and preserved are carried out by medical students in medical schools as a part of the teaching in subjects such as anatomy, pathology and forensic medicine. Consequently, dissection is typically conducted in a morgue or in an anatomy lab.

A prosector is a person with the special task of preparing a dissection for demonstration, usually in medical schools or hospitals. Many important anatomists began their careers as prosectors working for lecturers and demonstrators in anatomy and pathology.

Gross anatomy is the study of anatomy at the visible or macroscopic level. The counterpart to gross anatomy is the field of histology, which studies microscopic anatomy. Gross anatomy of the human body or other animals seeks to understand the relationship between components of an organism in order to gain a greater appreciation of the roles of those components and their relationships in maintaining the functions of life. The study of gross anatomy can be performed on deceased organisms using dissection or on living organisms using medical imaging. Education in the gross anatomy of humans is included training for most health professionals.

Medical education is education related to the practice of being a medical practitioner, including the initial training to become a physician and additional training thereafter.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp is a 1632 oil painting on canvas by Rembrandt housed in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, the Netherlands. It was originally created to be displayed by the Surgeons Guild in their meeting room. The painting is regarded as one of Rembrandt's early masterpieces.

Western University of Health Sciences (WesternU) is a private medical university in Pomona, California. With an enrollment of 3,724 students (2022–23), WesternU offers more than twenty academic programs in multiple colleges. It also operates an additional campus in Lebanon, Oregon.

A tissue bank is an establishment that collects and recovers human cadaver tissue for the purposes of medical research, education and allograft transplantation. A tissue bank may also refer to a location where biomedical tissue is stored under cryogenic conditions and is generally used in a more clinical sense.

An écorché is a figure drawn, painted, or sculpted showing the muscles of the body without skin, normally as a figure study for another work or as an exercise for a student artist. The Renaissance-era architect, theorist and all-around Renaissance man Leon Battista Alberti recommended that when painters intend to depict a nude, they should first arrange the muscles and bones, then depict the overlying skin.

A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body. Cadavers are used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Students in medical school study and dissect cadavers as a part of their education. Others who study cadavers include archaeologists and arts students. In addition, a cadaver may be used in the development and evaluation of surgical instruments.

The Medical Renaissance, from around 1400 to 1700 CE, was a period of progress in European medical knowledge, with renewed interest in the ideas of the ancient Greek, Roman civilizations and Islamic medicine, following the translation into Medieval Latin of many works from these societies. Medical discoveries during the Medical Renaissance are credited with paving the way for modern medicine.

Night Doctors are bogeymen of African American folklore, resulting from some factual basis.

A medical animation is a short educational film, usually based around a physiological or surgical topic, that is rendered using 3D computer graphics. While it may be intended for an array of audiences, the medical animation is most commonly utilized as an instructional tool for medical professionals or their patients.

The Western University College of Veterinary Medicine is a non-profit, private, veterinary medical school at Western University of Health Sciences located in Pomona, in the US state of California. The college consists of about 400 veterinary medical students, and confers the degree Doctor of Veterinary Medicine. The college was established in 1998 as the first veterinary school to open in the country in 20 years. The college is fully accredited by the American Veterinary Medical Association.

Clinical empathy is expressed as the skill of understanding what a patient says and feels, and effectively communicating this understanding to the patient. The opposite of clinical empathy is clinical detachment. Detached concern, or clinical detachment, is the ability to distance oneself from the patient in order to serve the patient from an objective standpoint. For physicians to maximize their role as providers, a balance must be developed between clinical detachment and clinical empathy.

Susan Marie Stover is a professor of veterinary anatomy at the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine and director of the J.D. Wheat Veterinary Orthopedic Research Laboratory. One of the focuses of her wide-ranging research is musculoskeletal injuries in racehorses, particularly catastrophic breakdowns. Her identification of risk factors has resulted in improved early detection and changes to horse training and surgical repair methods. On July 30, 2016, Stover received the Lifetime Excellence in Research Award from the American Veterinary Medical Association. In August 2016, she was selected for induction into the University of Kentucky Equine Research Hall of Fame.

The Calgary–Cambridge model is a method for structuring medical interviews. It focuses on giving a clear structure of initiating a session, gathering information, physical examination, explaining results and planning, and closing a session. It is popular in medical education in many countries.

The Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the Ankara University is a school of veterinary medicine in Ankara.

References

- ↑ "Prosection." In Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary. 30th ed. Douglas Anderson, ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders, 2007. ISBN 0-7216-0146-4

- ↑ "Prosector." In Stedman's Medical Dictionary. 25th ed. William R. Hensyl, ed. Baltimore, MD.:Williams & Wilkins, 1990. ISBN 0-683-07916-6

- ↑ Keith L. Moore, Arthur F. Dalley, and A.M.R. Agur (2006). Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-3639-0

- 1 2 Debra Berube, Christine Murray, and Kathleen Schultze (1999). "Cadaver and Computer Use in the Teaching of Gross Anatomy in Physical Therapy Education". Journal of Physical Therapy Education.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Siri Martinsen and Nick Jukes (2005). "Towards a Humane Veterinary Education". Journal of Veterinary Medical Education . 32 (4): 454–60. doi: 10.3138/jvme.32.4.454 . PMID 16421828. S2CID 18076050.

- ↑ Norman Gustavson (1988). "The Effect of Human Dissection on First-Year Students and Implications for the Doctor-Patient Relationship". Journal of Medical Education. 63 (1): 62–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198801000-00011 . PMID 3336047.

- ↑ J.A. Provo and C.H. Lamar (1995). "Prosection as an Approach to Student-centered Learning in Veterinary Gross Anatomy". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 206 (2): 158–61. PMID 7751212.

- ↑ Othman Mansor (1996). "Use of Plastinated Specimen in a Medical School With a Fully Integrated Curriculum" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for Plastination. 11: 16.

- ↑ Rafael M. Latorre, Mari P. García-Sanz, Matilde Moreno, Fuensanta Hernández, Francisco Gil, Octavio López, Maria D. Ayala, Gregorio Ramírez, Jose M. Vázquez, Alberto Arencibia, and Robert W. Henry (2007). "How Useful Is Plastination in Learning Anatomy?". Journal of Veterinary Medical Education . 34 (2): 172–6. doi:10.3138/jvme.34.2.172. hdl: 10553/47094 . PMID 17446645.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ann T. Stotter, A.J. Becket, J.P.R. Hansen, I. Capperauld, H.A.F. Dudley (1986). "Simulation in Surgical Training Using Freeze Dried Material". British Journal of Surgery. 73 (1): 52–4. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800730122. PMID 3512022. S2CID 20437420.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ C.L. Greenfield, A.L. Johnson, C.W. Smith, S.M. Marretta, J.A. Farmer, and L. Klippert (1994). "Integrating Alternative Models into the Existing Surgical Curriculum". Journal of Veterinary Medical Education . 21.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ J.F. Guy and A.J. Frisby (1992). "Using Interactive Videodiscs to Teach Gross Anatomy to Undergraduates at the Ohio State University". Academic Medicine. 67 (2): 132–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199202000-00021 . PMID 1546993.

- ↑ D.J. Griffon, P. Cronin, B. Kirby, and D.F. Cottrell (2000). "Evaluation of a Hemostasis Model for Teaching Ovariohysterectomy in Veterinary Surgery". Veterinary Surgery. 29 (4): 309–16. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2000.7541 . PMID 10917280.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ J. McLachlan, J. Bligh, P. Bradley, and J. Searle (2004). "Teaching anatomy without cadavers". Medical Education. 38 (4): 418–424. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01795.x. PMID 15025643. S2CID 32685938.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Christine Laura Theoret, Éric-Norman Carmel, and Sonia Bernier (2007). "Why Dissection Videos Should Not Replace Cadaver Prosections in the Gross Veterinary Anatomy Curriculum: Results from a Comparative Study". Journal of Veterinary Medical Education . 34 (2): 151–6. doi: 10.3138/jvme.34.2.151 . PMID 17446641.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ S.A. Azer and N. Eizenberg (2007). "Do We Need Dissection in an Integrated Problem-Based Learning Medical Course? Perceptions of First- and Second-Year Students". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 29 (2): 173–80. doi:10.1007/s00276-007-0180-x. PMID 17318286. S2CID 35653703.

- ↑ J.L. Perry, and D.P. Kuehn (2006). "Using Cadavers for Teaching Anatomy of the Speech and Hearing Mechanisms". The ASHA Leader. 11 (12): 14–28. doi:10.1044/leader.FTR6.11122006.14.

- ↑ M.E. Gordinier, C.C. Granai, N.D. Jackson (1995). "The Effects of a Course in Cadaver Dissection on Resident Knowledge of Pelvic Anatomy: An Experimental Study". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 86 (1): 137–9. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(95)00076-4. PMID 7784009. S2CID 36565498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ G.R. Bernard (1972). "Prosection Demonstrations as Substitutes for the Conventional Human Gross Anatomy Laboratory". Journal of Medical Education. 47 (9): 724–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197209000-00007 . PMID 5057480.

- ↑ Karl K. White, Lynn G. Wheaton, and Stephen A. Greene (1992). "Curriculum Change Related to Live Animal Use: A Four-Year Surgical Curriculum". Journal of Veterinary Medical Education . 19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ N.A. Jones, R.P. Olafson, and J. Sutin (1978). "Evaluation of a Gross Anatomy Program Without Dissection". Journal of Medical Education. 53 (3): 198–205. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197803000-00005 . PMID 344885.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Justin Alexander (1970). "Dissection Versus Prosection in the Teaching of Anatomy". Journal of Medical Education. 45 (8): 600–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197008000-00007 . PMID 5433736.

- ↑ Lisa M. Parker (2002). "What's Wrong With the Dead Body? Use of the Human Cadaver in Medical Education". Medical Journal of Australia. 176 (2): 74–6. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04290.x. PMID 11936290. S2CID 43839095.

- ↑ J.T. Soley and B. Kramer (2001). "Student Perceptions of Problem Topics/Concepts in a Traditional Veterinary Anatomy Course". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 72 (3): 150–7. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v72i3.639 . PMID 11811703.

- ↑ Martin A. Cake (2006). "Deep Dissection: Motivating Students beyond Rote Learning in Veterinary Anatomy". Journal of Veterinary Medical Education . 33.

- ↑ Jon Rosenson, Jeffrey A. Tabas, and Pat Patterson (2004). "Teaching Invasive Procedures to Medical Students". Journal of the American Medical Association. 291.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Gary J. Patronek and Annette Rauch (2007). "Systematic Review of Comparative Studies Examining Alternatives to the Harmful Use of Animals in Biomedical Education". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 230 (1): 37–43. doi:10.2460/javma.230.1.37. PMID 17199490.