Related Research Articles

Carl Linnaeus, also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné, was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organisms. He is known as the "father of modern taxonomy". Many of his writings were in Latin; his name is rendered in Latin as Carolus Linnæus and, after his 1761 ennoblement, as Carolus a Linné.

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an evolutionary perspective. This subfield of anthropology systematically studies human beings from a biological perspective.

On the Origin of Species is a work of scientific literature by Charles Darwin that is considered to be the foundation of evolutionary biology; it was published on 24 November 1859. Darwin's book introduced the scientific theory that populations evolve over the course of generations through a process of natural selection. The book presented a body of evidence that the diversity of life arose by common descent through a branching pattern of evolution. Darwin included evidence that he had collected on the Beagle expedition in the 1830s and his subsequent findings from research, correspondence, and experimentation.

Apes are a clade of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, which together with its sister group Cercopithecidae form the catarrhine clade, cladistically making them monkeys. Apes do not have tails due to a mutation of the TBXT gene. In traditional and non-scientific use, the term "ape" can include tailless primates taxonomically considered Cercopithecidae, and is thus not equivalent to the scientific taxon Hominoidea. There are two extant branches of the superfamily Hominoidea: the gibbons, or lesser apes; and the hominids, or great apes.

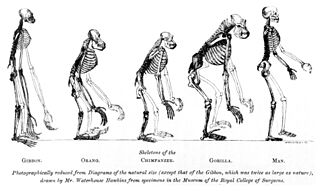

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny.

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist, and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He was also important as a race theorist.

The concept of race as a categorization of anatomically modern humans has an extensive history in Europe and the Americas. The contemporary word race itself is modern; historically it was used in the sense of "nation, ethnic group" during the 16th to 19th centuries. Race acquired its modern meaning in the field of physical anthropology through scientific racism starting in the 19th century. With the rise of modern genetics, the concept of distinct human races in a biological sense has become obsolete. In 2019, the American Association of Biological Anthropologists stated: "The belief in 'races' as natural aspects of human biology, and the structures of inequality (racism) that emerge from such beliefs, are among the most damaging elements in the human experience both today and in the past."

The parvorder Catarrhini, catarrhine monkeys, Old World anthropoids, or Old World monkeys, consisting of the Cercopithecoidea and apes (Hominoidea). In 1812, Geoffroy grouped those two groups together and established the name Catarrhini, "Old World monkeys",. Its sister in the infraorder Simiiformes is the parvorder Platyrrhini. There has been some resistance to directly designate apes as monkeys despite the scientific evidence, so "Old World monkey" may be taken to mean the Cercopithecoidea or the Catarrhini. That apes are monkeys was already realized by Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon in the 18th century. Linnaeus placed this group in 1758 together with what we now recognise as the tarsiers and the New World monkeys, in a single genus "Simia". The Catarrhini are all native to Africa and Asia. Members of this parvorder are called catarrhines.

The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biological adaptation distinct from, yet interconnected with, natural selection. The book discusses many related issues, including evolutionary psychology, evolutionary ethics, evolutionary musicology, differences between human races, differences between sexes, the dominant role of women in mate choice, and the relevance of the evolutionary theory to society.

William Ogilby (1805–1873) was an Irish-born zoologist who was at the forefront of classification and naming of animal species in the 1830s and served as Secretary of the Zoological Society of London from 1839 to 1847. He removed to Ireland during the Great Famine and later built the grand but architecturally dismal Altinaghree Castle. Mount Ogilby in Queensland was named for him in 1846.

Social degeneration was a widely influential concept at the interface of the social and biological sciences in the 18th and 19th centuries. During the 18th century, scientific thinkers including Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, and Immanuel Kant argued that humans shared a common origin but had degenerated over time due to differences in climate. This theory provided an explanation of where humans came from and why some people appeared differently from others. In contrast, degenerationists in the 19th century feared that civilization might be in decline and that the causes of decline lay in biological change. These ideas derived from pre-scientific concepts of heredity with Lamarckian emphasis on biological development through purpose and habit. Degeneration concepts were often associated with authoritarian political attitudes, including militarism and scientific racism, and a preoccupation with eugenics. The theory originated in racial concepts of ethnicity, recorded in the writings of such medical scientists as Johann Blumenbach and Robert Knox. From the 1850s, it became influential in psychiatry through the writings of Bénédict Morel, and in criminology with Cesare Lombroso. By the 1890s, in the work of Max Nordau and others, degeneration became a more general concept in social criticism. It also fed into the ideology of ethnic nationalism, attracting, among others, Maurice Barrès, Charles Maurras and the Action Française. Alexis Carrel, a French Nobel Laureate in Medicine, cited national degeneration as a rationale for a eugenics programme in collaborationist Vichy France.

Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature is an 1863 book by Thomas Henry Huxley, in which he gives evidence for the evolution of humans and apes from a common ancestor. It was the first book devoted to the topic of human evolution, and discussed much of the anatomical and other evidence. Backed by this evidence, the book proposed to a wide readership that evolution applied as fully to man as to all other life.

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (polygenesis). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no longer favor the polygenic model, with the monogenic "Out of Africa" hypothesis and its variants being the most widely accepted models for human origins. Historically, polygenism has been used to advance racial inequality.

Devolution, de-evolution, or backward evolution is the notion that species can revert to supposedly more primitive forms over time. The concept relates to the idea that evolution has a purpose (teleology) and is progressive (orthogenesis), for example that feet might be better than hooves or lungs than gills. However, evolutionary biology makes no such assumptions, and natural selection shapes adaptations with no foreknowledge of any kind. It is possible for small changes to be reversed by chance or selection, but this is no different from the normal course of evolution and as such de-evolution is not compatible with a proper understanding of evolution due to natural selection.

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as the simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes, which constitutes an incomplete paraphyletic grouping; however, in the broader sense based on cladistics, apes (Hominoidea) are also included, making the terms monkeys and simians synonyms in regards to their scope.

Frederic Wood Jones FRS, usually referred to as Wood Jones, was a British observational naturalist, embryologist, anatomist and anthropologist, who spent considerable time in Australia.

Sir Richard Owen was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

The Great Hippocampus Question was a 19th-century scientific controversy about the anatomy of ape and human uniqueness. The dispute between Thomas Henry Huxley and Richard Owen became central to the scientific debate on human evolution that followed Charles Darwin's publication of On the Origin of Species. The name comes from the title of a satire the Reverend Charles Kingsley wrote about the arguments, which in modified form appeared as "the great hippopotamus test" in Kingsley's 1863 book for children, The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby. Together with other humorous skits on the topic, this helped to spread and popularise Darwin's ideas on evolution.

Before Charles Darwin and his groundbreaking theory of evolution, primates were mainly used as caricatures of human nature. Although comparisons between man and animal are rather old, it was not until the findings of science that mankind recognised itself as a part of the animal kingdom. Caricatures of Darwin and his evolutionary theory reveal how closely science was intertwined with both the arts and the public during the Victorian era. They display the general perception of Darwin, his "monkey theory" and apes in 19th-century England.

Thomas Bendyshe (1827–1886) was an English barrister and academic, known as a magazine proprietor and translator.

References

- ↑ Blumenbach, Johann Friedrich (1825). A Manual of the Elements of Natural History. W. Simpkin & R. Marshall.

- ↑ Wilkins, Adam S. (2 January 2017). "History of the Face II: From Early Primates to Modern Humans". Making Faces. Belknap Press. p. 172. ISBN 9780674725522.

- ↑ "bimana". Merriam-Webster Dictionary . Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bimana". Encyclopædia Britannica . Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 946.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). London: John Murray. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8014-2085-6 . Retrieved 6 November 2021.