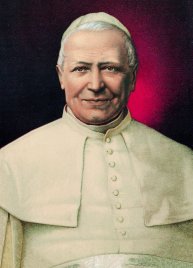

Quibus quantisque malis was a papal allocution of Pius IX addressed to the Consistory of Cardinals on April 20, 1849, [1] discussing the recent political atmosphere.

Pius IX was elected Pope in June 1846, during a time of political agitation which ultimately led to the brief Roman Republic of 1849. In Quibus quantusque, Pius gives a retrospective analysis of his first three years as Pope. He discusses some of the most important events, his intentions and the maneuvering of certain revolutionary elements who worked to capitalize on them. [2] One of his first acts was to declare an amnesty for all the political prisoners held in the papal jails. Revolutionaries in Rome exploited Pius IX's concessions, and continuously stirred up the populace to exert pressure in order to obtain additional ones. [3]

And it escapes no one that many who had been generously given that pardon not only did not change their thoughts at all, as We were hoping, but instead, as they persisted each day more bitterly in their designs and machinations, there was nothing that they left undone, nothing that they did not dare, nothing that they did not try, to shake and overthrow the civil Principate of the Roman Pontiff and his government, as they had already been planning for a long time, and at the same time, they brought a most bitter war against Our Most Holy Religion. [4]

While the discourse does not specifically mention Freemasonry, Hermann Gruber, writing in the Catholic Encyclopedia, lists it among the papal pronouncements against Freemasonry. [5] and by Masonic sources as equating Freemasonry with socialism and communism. [6] An English translation has been published online.