The Aryan race is an obsolete historical race concept that emerged in the late-19th century to describe people who descend from the Proto-Indo-Europeans as a racial grouping. The terminology derives from the historical usage of Aryan, used by modern Indo-Iranians as an epithet of "noble". Anthropological, historical, and archaeological evidence does not support the validity of this concept.

The master race is a pseudoscientific concept in Nazi ideology in which the putative "Aryan race" is deemed the pinnacle of human racial hierarchy. Members were referred to as "Herrenmenschen".

Joseph Arthur de Gobineau was a French aristocrat and anthropologist, who is best known for helping to legitimise racism by the use of scientific race theory and "racial demography", and for developing the theory of the Aryan master race and Nordicism. Known to his contemporaries as a novelist, diplomat and travel writer, he was an elitist who, in the immediate aftermath of the Revolutions of 1848, wrote An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races. In it he argued that aristocrats were superior to commoners and that aristocrats possessed more Aryan genetic traits because of less interbreeding with inferior races.

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist, and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He has been called the "founder of racial classifications."

The concept of race as a categorization of anatomically modern humans has an extensive history in Europe and the Americas. The contemporary word race itself is modern; historically it was used in the sense of "nation, ethnic group" during the 16th to 19th centuries. Race acquired its modern meaning in the field of physical anthropology through scientific racism starting in the 19th century. With the rise of modern genetics, the concept of distinct human races in a biological sense has become obsolete. In 2019, the American Association of Biological Anthropologists stated: "The belief in 'races' as natural aspects of human biology, and the structures of inequality (racism) that emerge from such beliefs, are among the most damaging elements in the human experience both today and in the past."

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that the human species can be subdivided into biologically distinct taxa called "races", and that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism, racial inferiority, or racial superiority. Before the mid-20th century, scientific racism was accepted throughout the scientific community, but it is no longer considered scientific. The division of humankind into biologically separate groups, along with the assignment of particular physical and mental characteristics to these groups through constructing and applying corresponding explanatory models, is referred to as racialism, race realism, or race science by those who support these ideas. Modern scientific consensus rejects this view as being irreconcilable with modern genetic research.

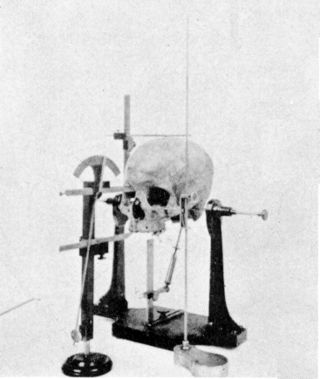

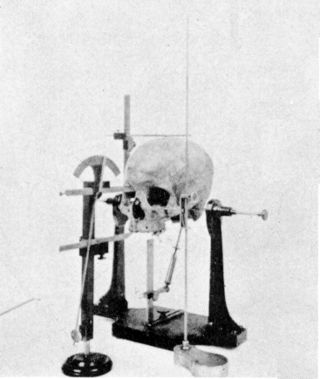

Craniometry is measurement of the cranium, usually the human cranium. It is a subset of cephalometry, measurement of the head, which in humans is a subset of anthropometry, measurement of the human body. It is distinct from phrenology, the pseudoscience that tried to link personality and character to head shape, and physiognomy, which tried the same for facial features. However, these fields have all claimed the ability to predict traits or intelligence.

Social degeneration was a widely influential concept at the interface of the social and biological sciences in the 18th and 19th centuries. During the 18th century, scientific thinkers including Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, and Immanuel Kant argued that humans shared a common origin but had degenerated over time due to differences in climate. This theory provided an explanation of where humans came from and why some people appeared differently from others. In contrast, degenerationists in the 19th century feared that civilization might be in decline and that the causes of decline lay in biological change. These ideas derived from pre-scientific concepts of heredity with Lamarckian emphasis on biological development through purpose and habit. Degeneration concepts were often associated with authoritarian political attitudes, including militarism and scientific racism, and a preoccupation with eugenics. The theory originated in racial concepts of ethnicity, recorded in the writings of such medical scientists as Johann Blumenbach and Robert Knox. From the 1850s, it became influential in psychiatry through the writings of Bénédict Morel, and in criminology with Cesare Lombroso. By the 1890s, in the work of Max Nordau and others, degeneration became a more general concept in social criticism. It also fed into the ideology of ethnic nationalism, attracting, among others, Maurice Barrès, Charles Maurras and the Action Française. Alexis Carrel, a French Nobel Laureate in Medicine, cited national degeneration as a rationale for a eugenics programme in collaborationist Vichy France.

Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines is a racist and pseudoscientific work of French writer Arthur de Gobineau, which argues that there are intellectual differences between human races, that civilizations decline and fall when the races are mixed and that the white race is superior. It is today considered to be one of the earliest examples of scientific racialism.

The Nordic race is an obsolete racial concept which originated in 19th-century anthropology. It was once considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming that its ancestral homelands were Northwestern and Northern Europe, particularly to populations such as Anglo-Saxons, Germanic peoples, Balts, Baltic Finns, Northern French, and certain Celts, Slavs and Ghegs. The supposed physical traits of the Nordics included light eyes, light skin, tall stature, and dolichocephalic skull; their psychological traits were deemed to be truthfulness, equitability, a competitive spirit, naivete, reservedness, and individualism. In the early 20th century, the belief that the Nordic race constituted the superior branch of the Caucasian race gave rise to the ideology of Nordicism.

Nordicism is an ideology which views the historical race concept of the "Nordic race" as an endangered and superior racial group. Some notable and influential Nordicist works include Madison Grant's book The Passing of the Great Race (1916); Arthur de Gobineau's An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (1853); the various writings of Lothrop Stoddard; Houston Stewart Chamberlain's The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1899); and, to a lesser extent, William Z. Ripley’s The Races of Europe (1899). The ideology became popular in the late-19th and 20th centuries in Germanic-speaking Europe, Northwestern Europe, Central Europe, and Northern Europe, as well as in North America and Australia.

Capoid race is a grouping formerly used for the Khoikhoi and San peoples in the context of a now-outdated model of dividing humanity into different races. The term was introduced by Carleton S. Coon in 1962 and named for the Cape of Good Hope. Coon proposed that the term "Negroid" should be abandoned, and the sub-Saharan African populations of West African stock should be termed "Congoid" instead.

Identifying human races in terms of skin colour, at least as one among several physiological characteristics, has been common since antiquity. Such divisions appeared in rabbinical literature and in early modern scholarship, usually dividing humankind into four or five categories, with colour-based labels: red, yellow, black, white, and sometimes brown. It was long recognized that the number of categories is arbitrary and subjective, and different ethnic groups were placed in different categories at different points in time. François Bernier (1684) doubted the validity of using skin color as a racial characteristic, and Charles Darwin (1871) emphasized the gradual differences between categories. Today there is broad agreement among scientists that typological conceptions of race have no scientific basis.

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (polygenesis). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views find little merit in any polygenic model due to an increased understanding of speciation in a human context, with the monogenic "Out of Africa" hypothesis and its variants being the most widely accepted models for human origins. Polygenism has historically been heavily used in service of white supremacist ideas and practices, denying a common origin between European and non-European peoples. It can be distinguished between Biblical polygenism, describing a Pre-Adamite or Co-Adamite origin of certain races in the context of the Genesis narrative of Adam and Eve, and scientific polygenism, attempting to find a taxonomic basis for ideas of racial science.

François Bernier was a French physician and traveller. He was born in Joué-Etiau in Anjou. He stayed for around 12 years in India.

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all human races. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the assumptions of scientific racism came under scrutiny both from religious groups and in the light of developments in the life sciences and human science. It was integral to the early conceptions of ethnology.

The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific book by American lawyer, anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theory of Nordic superiority, claiming that the "Nordic race" is inherently superior to other human "races". The theory and the book were praised by Adolf Hitler and other Nazis.

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews based on a belief or assertion that Jews constitute a distinct race that has inherent traits or characteristics that appear in some way abhorrent or inherently inferior or otherwise different from the traits or characteristics of the rest of a society. The abhorrence may find expression in the form of discrimination, stereotypes or caricatures. Racial antisemitism may present Jews, as a group, as a threat in some way to the values or safety of a society. Racial antisemitism can seem deeper-rooted than religious antisemitism, because for religious antisemites conversion of Jews remains an option and once converted the "Jew" is gone. In the context of racial antisemitism Jews cannot get rid of their Jewishness.

Mongoloid is an obsolete racial grouping of various peoples indigenous to large parts of Asia, the Americas, and some regions in Europe and Oceania. The term is derived from a now-disproven theory of biological race. In the past, other terms such as "Mongolian race", "yellow", "Asiatic" and "Oriental" have been used as synonyms.

The French aristocrat Arthur de Gobineau developed a set of ideas that were influential during his life and some of them that impacted later social thinkers, such politicians, anthropologists, and sociologists. While still alive, he was a major influence on "Gobinism", also known as Gobineauism, an academic, political and social movement formed in 19th-century Germany. An ethnically pro-Germanic, anti-national and particularly anti-French ideology, the movement influenced German nationalists and intellectuals such as Richard Wagner and Friedrich Nietzsche.