Human rights in Uganda have trended for the past decades towards increasing harassment of the opposition, cracking down on NGOs which work on election and term limits, corruption, land rights, environmental issues, womens, children and gay rights. In 2012, the Relief Web sponsored Humanitarian Profile – 2012 said Uganda made considerable developments Since at least 2013 the Freedom in the World report by Freedom House has identified Uganda as a country considered to be "Not Free".There are several areas of concern when it comes to human rights in Uganda, and the "Not Free" classification is due to both low political rights and civil liberties rankings.

Fionnuala Ní Aoláin is an Irish academic lawyer specialising in human rights law. She is the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism for the United Nations Human Rights Council since August 1, 2017.

Juan E. Méndez is an Argentine lawyer, former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and a human rights activist known for his work on behalf of political prisoners.

Israel's policies and actions in its ongoing occupation of the Palestinian territories have drawn accusations that it is committing the crime of apartheid. Leading Palestinian, Israeli and international human rights groups have said that the totality and severity of the human rights violations against the Palestinian population in the occupied territories, and by some in Israel proper, amount to the crime against humanity of apartheid. Israel and some of its Western allies have rejected the accusation, with the former often labeling the charge antisemitic.

Gender apartheid is the economic and social sexual discrimination against individuals because of their gender or sex. It is a system enforced by using either physical or legal practices to relegate individuals to subordinate positions. Feminist scholar Phyllis Chesler, professor of psychology and women's studies, defines the phenomenon as "practices which condemn girls and women to a separate and subordinate sub-existence and which turn boys and men into the permanent guardians of their female relatives' chastity". Instances of gender apartheid lead not only to the social and economic disempowerment of individuals, but can also result in severe physical harm.

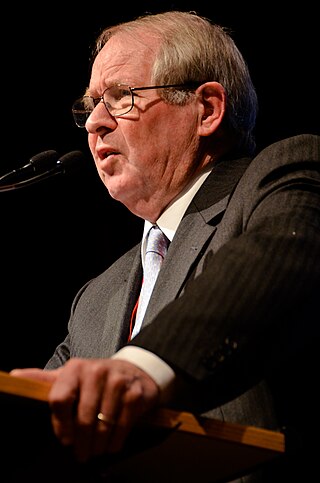

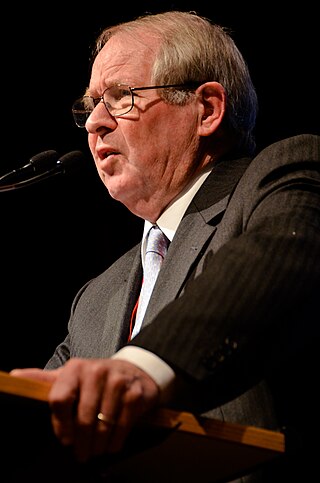

Christopher John Robert Dugard is a South African professor of international law. His main academic specializations are in Roman-Dutch law, public international law, jurisprudence, human rights, criminal procedure and international criminal law. He has served on the International Law Commission, the primary UN institution for the development of international law, and has been active in reporting on human-rights violations by Israel in the Palestinian territories.

Navanethem "Navi" Pillay is a South African jurist who served as the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights from 2008 to 2014. A South African of Indian Tamil origin, Pillay was the first non-white woman judge of the High Court of South Africa. She has also served as a judge of the International Criminal Court and President of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Her four-year term as High Commissioner for Human Rights began on 1 September 2008 and was extended an additional two years in 2012. In September 2014 Prince Zeid bin Ra'ad succeeded her in her position as High Commissioner for Human Rights. In April 2015, Pillay became the 16th Commissioner of the International Commission Against the Death Penalty. She is also one of the 25 leading figures on the Information and Democracy Commission launched by Reporters Without Borders.

Corrective rape, also called curative rape or homophobic rape, is a hate crime in which one or more people are raped because of their perceived sexual orientation, such as homosexuality or bisexuality. The common intended consequence of the rape, as claimed by the perpetrator, is to turn the person heterosexual.

The Yogyakarta Principles is a document about human rights in the areas of sexual orientation and gender identity that was published as the outcome of an international meeting of human rights groups in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, in November 2006. The principles were supplemented and expanded in 2017 to include new grounds of gender expression and sex characteristics and a number of new principles. However, the Principles have never been accepted by the United Nations (UN) and the attempt to make gender identity and sexual orientation new categories of non-discrimination has been repeatedly rejected by the General Assembly, the UN Human Rights Council and other UN bodies.

The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women was adopted without a vote by the United Nations General Assembly in the 48/104 resolution of 20 December 1993. Contained within it is the recognition of "the urgent need for the universal application to women of the rights and principles with regard to equality, security, liberty, integrity and dignity of all human beings". It recalls and embodies the same rights and principles as those enshrined in such instruments as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and Articles 1 and 2 provide the most widely used definition of violence against women.

On 4 March 1994 the Human Rights Council passed Resolution 1994/45 on the question of integrating the rights of women into the human rights mechanisms of the United Nations and the elimination of violence against women. This Resolution established the mandate of the "Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women its causes and consequences". The initial appointment was for a three-year period. As of November 2021 the special rapporteur was Reem Alsalem.

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a constitutional parliamentary democracy with an estimated population of 6,187,591. Police brutality, provincial power struggles, violence against women, and government corruption all contribute to the low awareness of basic human rights in the country.

The Republic of Uruguay is located in South America, between Argentina, Brazil and the South Atlantic Ocean, with a population of 3,332,972. Uruguay gained independence and sovereignty from Spain in 1828 and has full control over its internal and external affairs. From 1973 to 1985 Uruguay was governed by a civil-military dictatorship which committed numerous human rights abuses.

Agnès Callamard is a French human-rights activist who is the Secretary General of Amnesty International. She was previously the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions appointed by the United Nations Human Rights Council, and the former Director of the Columbia University Global Freedom of Expression project.

2014 was described as a watershed year for women's rights, by newspapers such as The Guardian. It was described as a year in which women's voices acquired greater legitimacy and authority. Time magazine said 2014 "may have been the best year for women since the dawn of time". However, The Huffington Post called it "a bad year for women, but a good year for feminism". San Francisco writer Rebecca Solnit argued that it was "a year of feminist insurrection against male violence" and a "lurch forward" in the history of feminism, and The Guardian said the "globalisation of protest" at violence against women was "groundbreaking", and that social media had enabled a "new version of feminist solidarity".

Urmila Bhoola is a South African international human rights lawyer who has worked on human rights, labour rights, women's rights, child protection, human trafficking, forced labour and ending modern slavery in South Africa, Malaysia, Fiji and the Oceanic islands, Nepal and Geneva.

Intersex people in South Africa have some of the same rights as other people, but with significant gaps in protection from non-consensual cosmetic medical interventions and protection from discrimination. The country was the first to explicitly include intersex people in anti-discrimination law.

This article provides an overview of marital rape laws by country.

The Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women, better known as the Belém do Pará Convention, is an international human rights instrument adopted by the Inter-American Commission of Women (CIM) of the Organization of American States (OAS) at a conference held in Belém do Pará, Brazil, on 9 June 1994. It is the first legally binding international treaty that criminalises all forms of violence against women, especially sexual violence. On 26 October 2004, the Follow-Up Mechanism (MESECVI) agency was established to ensure the State parties' compliance with the Convention.

Yakin Ertürk is a Turkish former United Nations special rapporteur on violence against women and board member of the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), and was a professor of Sociology.