Female genital mutilation (FGM) is the cutting or removal of some or all of the vulva for non-medical reasons. FGM prevalence varies worldwide, but is majorly present in some countries of Africa, Asia and Middle East, and within their diasporas. As of 2024, UNICEF estimates that worldwide 230 million girls and women had been subjected to one or more types of FGM.

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, these rights are institutionalized or supported by law, local custom, and behavior, whereas in others, they are ignored and suppressed. They differ from broader notions of human rights through claims of an inherent historical and traditional bias against the exercise of rights by women and girls, in favor of men and boys.

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to reproduction and reproductive health that vary amongst countries around the world. The World Health Organization defines reproductive rights as follows:

Reproductive rights rest on the recognition of the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and to have the information and means to do so, and the right to attain the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health. They also include the right of all to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and violence.

The United Nations coordinated an International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo, Egypt, on 5–13 September 1994. Its resulting Programme of Action is the steering document for the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) is an international treaty adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly. Described as an international bill of rights for women, it was instituted on 3 September 1981 and has been ratified by 189 states. Over fifty countries that have ratified the convention have done so subject to certain declarations, reservations, and objections, including 38 countries who rejected the enforcement article 29, which addresses means of settlement for disputes concerning the interpretation or application of the convention. Australia's declaration noted the limitations on central government power resulting from its federal constitutional system. The United States and Palau have signed, but not ratified the treaty. The Holy See, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, and Tonga are not signatories to CEDAW.

The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights is an international human rights instrument that is intended to promote and protect human rights and basic freedoms in the African continent.

Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is a field of research, health care, and social activism that explores the health of an individual's reproductive system and sexual well-being during all stages of their life. Sexual and reproductive health is more commonly defined as sexual and reproductive health and rights, to encompass individual agency to make choices about their sexual and reproductive lives.

Contributing to the establishment of human rights system in Africa are the United Nations, international law and the African Union which have positively influenced the betterment the human rights situation in the continent. However, extensive human rights abuses still occur in many sections of the continent. Most of the violations can be attributed to political instability, racial discrimination, corruption, post-colonialism, economic scarcity, ignorance, illness, religious bigotry, debt and bad financial management, monopoly of power, lack/absence of judicial and press autonomy, and border conflicts. Many of the provisions contained in regional, national, continental, and global agreements remained unaccomplished.

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children(IAC) (French: Comité interafricain sur les pratiques traditionnelles affectant la santé des femmes et des enfants) is a non-governmental organization (NGO) which seeks to change social values and raise consciousness towards eliminating female genital mutilation (FGM) and other traditional practices which affect the health of women and children in Africa.

International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation is a United Nations-sponsored annual awareness day that takes place on February 6 as part of the UN's efforts to eradicate female genital mutilation. It was first introduced in 2003.

Women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo have not attained a position of full equality with men, with their struggle continuing to this day. Although the Mobutu regime paid lip service to the important role of women in society, and although women enjoy some legal rights, custom and legal constraints still limit their opportunities.

Research Action and Information Network for the Bodily Integrity of Women is an international non-governmental organisation working to eliminate female circumcision and female genital mutilation.

Nahid Toubia is a Sudanese surgeon and women's health rights activist, specializing in research into female genital mutilation.

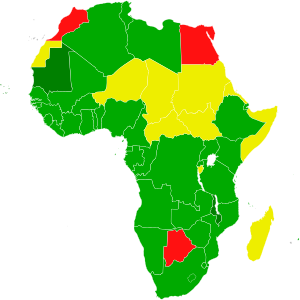

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting (FGC), female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and female circumcision, is practiced in 30 countries in western, eastern, and north-eastern Africa, in parts of the Middle East and Asia, and within some immigrant communities in Europe, North America and Australia, aswell as in specific minority enclaves in areas such as South Asia and Russia. The WHO defines the practice as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."

The culture, evolution, and history of women who were born in, live in, and are from the continent of Africa reflect the evolution and history of the African continent itself.

The status of women in Zambia has improved in recent years. Among other things, the maternal mortality rate has dropped and the National Assembly of Zambia has enacted multiple policies aimed at decreasing violence against women. However, progress is still needed. Most women have limited access to reproductive healthcare, and the total number of women infected with HIV in the country continues to rise. Moreover, violence against women in Zambia remains common. Child marriage rates in Zambia are some of the highest in the world, and women continue to experience high levels of physical and sexual violence.

Faiza Jama Mohamed is a Somalian women's rights activist, Africa Regional Director of Equality Now. She has been a prominent campaigner for the Maputo Protocol, and against female genital mutilation.

The legal status of female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting (FGC), differs widely across the world.

In the Gambia, abortion is illegal except to save the life of the mother or to prevent birth defects.

In Africa, abortion is subject to various national abortion laws. Most women in Africa live in countries with restrictive laws. Most countries in Africa are parties to the African Union's Maputo Protocol, the only international treaty that defines a right to abortion. Sub-Saharan Africa is the world region with the highest rates of unsafe abortions and abortion mortality. Most abortions in the region are unsafe. The region has the highest rate of unintended pregnancy, the primary motive for abortion. The most likely women to have abortions are young, unmarried, or urban. Post-abortion care is widely available.