Status

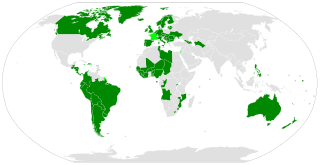

As of 14 March 2014 [update] , the following countries have signed or ratified the convention: [2]

| Signatory | Signed | Ratified | In force |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signed | 6 November 1997 |

|---|---|

| Location | Strasbourg |

| Effective | 1 March 2000 |

| Condition | 3 ratifications |

| Parties | 21 |

| Citations | ETS 166 |

| Languages |

The European Convention on Nationality (E.T.S. No. 166 [1] ) was signed in Strasbourg on 6 November 1997. It is a comprehensive convention of the Council of Europe dealing with the law of nationality. The convention is open for signature by the member States of the Council of Europe and the non-member States which have participated in its elaboration and for accession by other non-member States. The Convention came into force on 1 March 2000 after ratification by 3 countries. As of 2021 [update] , the convention has been signed by 29 countries and ratified by 21 of those countries. [2]

Article 4(d) provides that neither marriage nor dissolution of marriage shall automatically affect the nationality of either spouse, nor shall a change of nationality by one spouse during marriage automatically affect the nationality of their spouse. Common practice among states at the beginning of the 20th century was that a woman was to have the nationality of her husband; i.e., upon marrying a foreigner the wife would automatically acquire the nationality of her husband, and lose her previous nationality. Even after the nationality of a married woman was no longer dependent on the nationality of her husband, legal provisions were still retained which automatically naturalised married women, and sometimes married men as well. This led to a number of problems, such as loss of the spouses' original nationality, the spouse losing the right to consular assistance (since consular assistance cannot be provided to nationals under the jurisdiction of a foreign state of which they are also nationals), and becoming subject to military service obligations. Article 4d addresses this situation.

Article 5 provides that no discrimination shall exist in a state's internal nationality law on the grounds of "sex, religion, race, colour or national or ethnic origin". It also provides that a state shall not discriminate amongst its nationals on the basis of whether they hold their nationality by birth or acquired it subsequently.

Article 6 relates to the acquisition of nationality. It provides for nationality to be acquired at birth by descent from either parent to those born within the territory of the state. (States may exclude partially or fully children born abroad). It also provides for nationality by virtue of birth in the territory of state; however, states may limit this to only children who would be otherwise stateless. It requires the possibility of naturalisation, and provides that the period of residence required for eligibility cannot be more than ten years lawful and habitual residence. It also requires to "facilitate" the acquisition of nationality by certain persons, including spouses of nationals, children of its nationals born abroad, children one of whose parents has acquired the nationality, children adopted by a national, persons lawfully and habitually resident for a period before the age of eighteen, and stateless persons and refugees lawfully and habitually resident on its territory.

Article 7 regulates the involuntary loss of nationality. It provides that states may deprive their nationals of their nationality in only the cases of voluntary acquisition of another nationality, fraud or failure to provide relevant information when acquiring nationality, voluntary military service in a foreign military force, or adoption as a child by foreign nationals. It also provides for the possibility of loss of nationality for nationals habitually residing abroad. Finally, it provides loss of nationality for "conduct seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the State Party".

Article 8 provides nationals with the right to renounce their nationality, providing they do not thereby become stateless. States may however restrict this right with respect to nationals residing abroad. [1]

As of 14 March 2014 [update] , the following countries have signed or ratified the convention: [2]

| Signatory | Signed | Ratified | In force |

|---|---|---|---|

Swiss citizenship is the status of being a citizen of Switzerland and it can be obtained by birth or naturalisation.

Nationality law is the law of a sovereign state, and of each of its jurisdictions, that defines the legal manner in which a national identity is acquired and how it may be lost. In international law, the legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation are separated from the relationship between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Some nations domestically use the terms interchangeably, though by the 20th century, nationality had commonly come to mean the status of belonging to a particular nation with no regard to the type of governance which established a relationship between the nation and its people. In law, nationality describes the relationship of a national to the state under international law and citizenship describes the relationship of a citizen within the state under domestic statutes. Different regulatory agencies monitor legal compliance for nationality and citizenship. A person in a country of which he or she is not a national is generally regarded by that country as a foreigner or alien. A person who has no recognised nationality to any jurisdiction is regarded as stateless.

Italian nationality law is the law of Italy governing the acquisition, transmission and loss of Italian citizenship. Like many continental European countries it is largely based on jus sanguinis. It also incorporates many elements that are seen as favourable to the Italian diaspora. The Italian Parliament's 1992 update of Italian nationality law is Law no. 91, and came into force on 15 August 1992. Presidential decrees and ministerial directives, including several issued by the Ministry of the Interior, instruct the civil service how to apply Italy's citizenship-related laws.

Dutch nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds Dutch nationality. The primary law governing these requirements is the Dutch Nationality Act, which came into force on 1 January 1985. Regulations apply to the entire Kingdom of the Netherlands, which includes the country of the Netherlands itself, Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten.

Swedish nationality law determines entitlement to Swedish citizenship. Citizenship of Sweden is based primarily on the principle of jus sanguinis. In other words, citizenship is conferred primarily by birth to a Swedish parent, irrespective of place of birth.

Austrian nationality law details the conditions by which an individual is a national of Austria. The primary law governing these requirements is the Nationality Law, which came into force on 31 July 1985.

The citizenship law of the Czech Republic is based on the principles of jus sanguinis or "right by blood". In other words, descent from a Czech parent is the primary method of acquiring Czech citizenship. Birth on Czech territory without a Czech parent is in itself insufficient for the conferral of Czech citizenship. Every Czech citizen is also a citizen of the European Union. The law came into effect on 1 January 1993, the date of the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, and has been amended in 1993, 1995, 1996, 1999, 2002, 2003, and 2005. Since 1 January 2014, multiple citizenship under Czech law is allowed.

Polish nationality law is based primarily on the principle of jus sanguinis. Children born to at least one Polish parent acquire Polish citizenship irrespective of place of birth. Besides other things, Polish citizenship entitles the person to a Polish passport.

Hungarian nationality law is based on the principles of jus sanguinis. Hungarian citizenship can be acquired by descent from a Hungarian parent, or by naturalisation. A person born in Hungary to foreign parents does not generally acquire Hungarian citizenship. A Hungarian citizen is also a citizen of the European Union.

Nationality law of Greece is based on the principle of jus sanguinis. Greek citizenship may be acquired by descent or through naturalization. Greek law permits dual citizenship. A Greek national is a citizen of the European Union, and therefore entitled to the same rights as other EU citizens.

Turkish nationality law is based primarily on the principle of jus sanguinis. Children who are born to a Turkish mother or a Turkish father are Turkish citizens from birth. The intention to renounce Turkish citizenship is submitted in Turkey by a petition to the highest administrative official in the concerned person's place of residence, and when overseas to the Turkish consulate. Documents processed by these authorities are forwarded to the Ministry of Interior (Turkey) for appropriate action.

The Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness is a 1961 United Nations multilateral treaty whereby sovereign states agree to reduce the incidence of statelessness. The Convention was originally intended as a Protocol to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, while the 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons was adopted to cover stateless persons who are not refugees and therefore not within the scope of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

Estonian citizenship law details the conditions by which a person is a citizen of Estonia. The primary law currently governing these requirements is the Citizenship Act, which came into force on 1 April 1995.

Danish nationality law is governed by the Constitutional Act and the Consolidated Act of Danish Nationality. Danish nationality can be acquired in one of the following ways:

Moldovan nationality law dates back to June 2, 2000 and has been amended several times, with the latest modifications being made in 2014. It is based on the Constitution of Moldova. It is mainly based on Jus sanguinis.

Azerbaijani nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Azerbaijan, as amended; the Citizenship Law of Azerbaijan and its revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, an Azerbaijani national.

Batswana nationality law is regulated by the 1966 Constitution of Botswana, as amended; the Citizenship Act 1998, and its revisions; and international agreements entered into by the government of Botswana. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Botswana. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. The Botswana nationality is typically obtained on the principle of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth to parents with Botswana nationality. It can be granted to persons who have lived in the country for a specific period of time, who have performed distinguished service to the nation or who have an affiliation to the country through naturalisation.

Kenyan nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Kenya, as amended; the Kenya Citizenship and Immigration Act, and its revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Kenya. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. In Britain and thus the Commonwealth of Nations, though the terms are often used synonymously outside of law, they are governed by different statutes and regulated by different authorities. Kenyan nationality is typically obtained under the principle of jus soli, by being born in Kenya, or jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth in Kenya or abroad to parents with Kenyan nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through registration.

Basotho nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Lesotho, as amended; the Lesotho Citizenship Order, and its revisions; the 1983 Refugees Act; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Lesotho. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. In Britain and thus the Commonwealth of Nations, though the terms are often used synonymously outside of law, they are governed by different statutes and regulated by different authorities. Basotho nationality is typically obtained under the principle of jus soli, born in Lesotho, or jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth in Lesotho or abroad to parents with Basotho nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalisation.

Malawian nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Malawi, as amended; the Malawian Citizenship Act, and its revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Malawi. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual and the nation. Malawian nationality is typically obtained under the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Malawi, or jus sanguinis, born to a father with Malawian nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalisation.