In thermodynamics, an exothermic process is a thermodynamic process or reaction that releases energy from the system to its surroundings, usually in the form of heat, but also in a form of light, electricity, or sound. The term exothermic was first coined by 19th-century French chemist Marcellin Berthelot.

Thermochemistry is the study of the heat energy which is associated with chemical reactions and/or phase changes such as melting and boiling. A reaction may release or absorb energy, and a phase change may do the same. Thermochemistry focuses on the energy exchange between a system and its surroundings in the form of heat. Thermochemistry is useful in predicting reactant and product quantities throughout the course of a given reaction. In combination with entropy determinations, it is also used to predict whether a reaction is spontaneous or non-spontaneous, favorable or unfavorable.

In chemistry and thermodynamics, the standard enthalpy of formation or standard heat of formation of a compound is the change of enthalpy during the formation of 1 mole of the substance from its constituent elements in their reference state, with all substances in their standard states. The standard pressure value p⦵ = 105 Pa(= 100 kPa = 1 bar) is recommended by IUPAC, although prior to 1982 the value 1.00 atm (101.325 kPa) was used. There is no standard temperature. Its symbol is ΔfH⦵. The superscript Plimsoll on this symbol indicates that the process has occurred under standard conditions at the specified temperature (usually 25 °C or 298.15 K).

Fluorocarbons are chemical compounds with carbon-fluorine bonds. Compounds that contain many C-F bonds often have distinctive properties, e.g., enhanced stability, volatility, and hydrophobicity. Several fluorocarbons and their derivatives are commercial polymers, refrigerants, drugs, and anesthetics.

A flame is the visible, gaseous part of a fire. It is caused by a highly exothermic chemical reaction taking place in a thin zone. When flames are hot enough to have ionized gaseous components of sufficient density they are then considered plasma.

Hess's law of constant heat summation, also known simply as Hess' law, is a relationship in physical chemistry named after Germain Hess, a Swiss-born Russian chemist and physician who published it in 1840. The law states that the total enthalpy change during the complete course of a chemical reaction is independent of the sequence of steps taken.

In thermochemistry, an exothermic reaction is a "reaction for which the overall standard enthalpy change ΔH⚬ is negative." Exothermic reactions usually release heat. The term is often confused with exergonic reaction, which IUPAC defines as "... a reaction for which the overall standard Gibbs energy change ΔG⚬ is negative." A strongly exothermic reaction will usually also be exergonic because ΔH⚬ makes a major contribution to ΔG⚬. Most of the spectacular chemical reactions that are demonstrated in classrooms are exothermic and exergonic. The opposite is an endothermic reaction, which usually takes up heat and is driven by an entropy increase in the system.

Hans Peter Jørgen Julius Thomsen was a Danish chemist noted in thermochemistry for the Thomsen–Berthelot principle.

Oxygen fluorides are compounds of elements oxygen and fluorine with the general formula OnF2, where n = 1 to 6. Many different oxygen fluorides are known:

Cadmium fluoride (CdF2) is a mostly water-insoluble source of cadmium used in oxygen-sensitive applications, such as the production of metallic alloys. In extremely low concentrations (ppm), this and other fluoride compounds are used in limited medical treatment protocols. Fluoride compounds also have significant uses in synthetic organic chemistry. The standard enthalpy has been found to be -167.39 kcal. mole−1 and the Gibbs energy of formation has been found to be -155.4 kcal. mole−1, and the heat of sublimation was determined to be 76 kcal. mole−1.

Xenon difluoride is a powerful fluorinating agent with the chemical formula XeF

2, and one of the most stable xenon compounds. Like most covalent inorganic fluorides it is moisture-sensitive. It decomposes on contact with water vapor, but is otherwise stable in storage. Xenon difluoride is a dense, colourless crystalline solid.

Krypton difluoride, KrF2 is a chemical compound of krypton and fluorine. It was the first compound of krypton discovered. It is a volatile, colourless solid at room temperature. The structure of the KrF2 molecule is linear, with Kr−F distances of 188.9 pm. It reacts with strong Lewis acids to form salts of the KrF+ and Kr

2F+

3 cations.

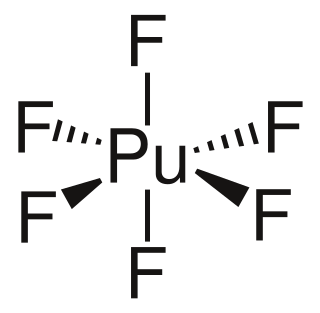

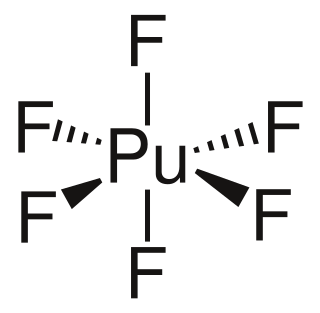

Plutonium hexafluoride is the highest fluoride of plutonium, and is of interest for laser enrichment of plutonium, in particular for the production of pure plutonium-239 from irradiated uranium. This pure plutonium is needed to avoid premature ignition of low-mass nuclear weapon designs by neutrons produced by spontaneous fission of plutonium-240.

Thiophosphoryl fluoride is an inorganic molecular gas with formula PSF3 containing phosphorus, sulfur and fluorine. It spontaneously ignites in air and burns with a cool flame. The discoverers were able to have flames around their hands without discomfort, and called it "probably one of the coldest flames known". The gas was discovered in 1888.

Fluorine azide or triazadienyl fluoride is a yellow green gas composed of nitrogen and fluorine with formula FN3. Its properties resemble those of ClN3, BrN3, and IN3. The bond between the fluorine atom and the nitrogen is very weak, leading to this substance being very unstable and prone to explosion. Calculations show the F–N–N angle to be around 102° with a straight line of 3 nitrogen atoms.

Sandra Charlene Greer is an American physical chemist who has held important academic and administrative positions at both the University of Maryland, College Park and Mills College. Her area of study is the thermodynamics of fluids, especially polymer solutions and phase transitions. She has received awards for her scientific contributions, and for her advocacy for women in science and her work on ethics in science.

Lucia V. Streng was a Russian Empire-born American chemist. She spent much of her career studying the noble gases and their properties, successfully synthesizing krypton difluoride. She and her husband, Alex G. Streng, both held positions at Temple University.

Jean'ne Marie Shreeve is an American chemist known for her studies of fluorine compounds and explosives. She has held her namesake professorship at the University of Idaho since 2004.

Vladimir Fedorovich Luginin was a Russian physical chemist. His main work was in thermochemistry, and dealt with the heat of combustion of organic compounds.

Radon compounds are compounds formed by the element radon (Rn). Radon is a member of the zero-valence elements that are called noble gases, and is chemically not very reactive. The 3.8-day half-life of radon-222 makes it useful in physical sciences as a natural tracer. Because radon is a gas at standard conditions, unlike its decay-chain parents, it can readily be extracted from them for research.