Theatrical ritual

The earliest example of theatrical ritual is found in the Regularis Concordia with the rule of the divine service, referred to as the quem quaeritis. This rule includes the oldest documented theatrical recital of alternating song to be performed the night before Easter. The Regularis states that the importance of this visual ritual was to aid those who could not read or understand Latin in the understanding of the ritual. The Latin quote below describes: "An alternating song between the three women approaching the grave, and the angel watching on it, shall be recited; the friar who sings the words of the angel is to take his seat, clad in an alb and with a palm-twig in his hand, in a place representing the tomb; three other friars, wearing hooded capes and with censers in their hands, are to approach the tomb at a slow pace, as if in quest of something"

Quem quaeritis in sepulchro, o Christicolae?Jesum Nazarenum cruifixum, o caelicolae.Non est hic, surrexit, sicut praedixerat. Ite, nuntiate, quia surrexit de sepulchro. [11]

Dunstan,, was an English bishop and Benedictine monk. He was successively Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised. His work restored monastic life in England and reformed the English Church. His 11th-century biographer Osbern, himself an artist and scribe, states that Dunstan was skilled in "making a picture and forming letters", as were other clergy of his age who reached senior rank.

Eadwig was King of England from 23 November 955 until his death in 959. He was the elder son of Edmund I and his first wife Ælfgifu, who died in 944. Eadwig and his brother Edgar were young children when their father was killed trying to rescue his seneschal from attack by an outlawed thief on 26 May 946. As Edmund's sons were too young to rule he was succeeded by his brother Eadred, who suffered from ill health and died unmarried in his early 30s.

Edward the Martyr was King of the English from 8 July 975 until he was killed in 978. He was the eldest son of King Edgar. On Edgar's death, the succession to the throne was contested between Edward's supporters and those of his younger half-brother, the future King Æthelred the Unready. As they were both children, it is unlikely that they played an active role in the dispute, which was probably between rival family alliances. Edward's principal supporters were Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Æthelwine, Ealdorman of East Anglia, while Æthelred was backed by his mother, Queen Ælfthryth and her friend Æthelwold, Bishop of Winchester. The dispute was quickly settled. Edward was chosen as king and Æthelred received the lands traditionally allocated to the king's eldest son in compensation.

Edgar was King of the English from 959 until his death in 975. He became king of all England on his brother's death. He was the younger son of King Edmund I and his first wife Ælfgifu. A detailed account of Edgar's reign is not possible, because only a few events were recorded by chroniclers and monastic writers were more interested in recording the activities of the leaders of the church.

Eadred was King of the English from 26 May 946 until his death in 955. He was the younger son of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu, and a grandson of Alfred the Great. His elder brother, Edmund, was killed trying to protect his seneschal from an attack by a violent thief. Edmund's two sons, Eadwig and Edgar, were then young children, so Eadred became king. He suffered from ill health in the last years of his life and he died at the age of a little over thirty, having never married. He was succeeded successively by his nephews, Eadwig and Edgar.

Ælfric of Eynsham was an English abbot and a student of Æthelwold of Winchester, and a consummate, prolific writer in Old English of hagiography, homilies, biblical commentaries, and other genres. He is also known variously as Ælfric the Grammarian, Ælfric of Cerne, and Ælfric the Homilist. In the view of Peter Hunter Blair, he was "a man comparable both in the quantity of his writings and in the quality of his mind even with Bede himself." According to Claudio Leonardi, he "represented the highest pinnacle of Benedictine reform and Anglo-Saxon literature".

West Saxon is the term applied to the two different dialects Early West Saxon and Late West Saxon with West Saxon being one of the four distinct regional dialects of Old English. The three others were Kentish, Mercian and Northumbrian. West Saxon was the language of the kingdom of Wessex, and was the basis for successive widely used literary forms of Old English: the Early West Saxon of Alfred the Great's time, and the Late West Saxon of the late 10th and 11th centuries. Due to the Saxons' establishment as a politically dominant force in the Old English period, the West Saxon dialects became the strongest dialects in Old English manuscript writing.

Ælfgifu was Queen of the English as wife of King Eadwig of England for a brief period of time until 957 or 958. What little is known of her comes primarily by way of Anglo-Saxon charters, possibly including a will, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and hostile anecdotes in works of hagiography. Her union with the king, annulled within a few years of Eadwig's reign, seems to have been a target for factional rivalries which surrounded the throne in the late 950s. By c. 1000, when the careers of the Benedictine reformers Dunstan and Oswald became the subject of hagiography, its memory had suffered heavy degradation. In the mid-960s, however, she appears to have become a well-to-do landowner on good terms with King Edgar and, through her will, a generous benefactress of ecclesiastical houses associated with the royal family, notably the Old Minster and New Minster at Winchester.

The Benedictional of St Æthelwold is a 10th-century illuminated benedictional, the most important surviving work of the Anglo-Saxon Winchester School of illumination. It contains the various pontifical blessings used during Mass on the differing days of the ecclesiastical year, along with a form for blessing the candles used during the Feast of the Purification. The manuscript was written by the monk Godeman at the request of Æthelwold, Bishop of Winchester.

Æthelwold of Winchester was Bishop of Winchester from 963 to 984 and one of the leaders of the tenth-century monastic reform movement in Anglo-Saxon England.

Oswald of Worcester was Archbishop of York from 972 to his death in 992. He was of Danish ancestry, but brought up by his uncle, Oda of Canterbury, who sent him to France to the abbey of Fleury to become a monk. After a number of years at Fleury, Oswald returned to England at the request of his uncle, who died before Oswald returned. With his uncle's death, Oswald needed a patron and turned to another kinsman, Oskytel, who had recently become Archbishop of York. His activity for Oskytel attracted the notice of Archbishop Dunstan who had Oswald consecrated as Bishop of Worcester in 961. In 972, Oswald was promoted to the see of York, although he continued to hold Worcester also.

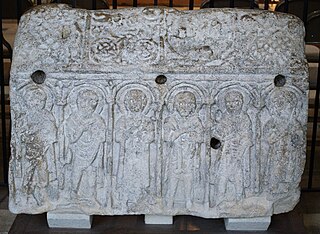

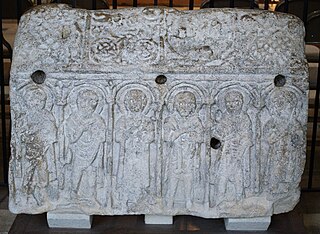

Medeshamstede was the name of Peterborough in the Anglo-Saxon period. It was the site of a monastery founded around the middle of the 7th century, which was an important feature in the kingdom of Mercia from the outset. Little is known of its founder and first abbot, Sexwulf, though he was himself an important figure, and later became bishop of Mercia. Medeshamstede soon acquired a string of daughter churches, and was a centre for an Anglo-Saxon sculptural style.

Ælfheah the Bald is the commonly used name for Ælfheah, the first English Bishop of Winchester of that name. He is sometimes known as Alphege, an older translation of his Old English name.

The Old Minster was the Anglo-Saxon cathedral for the English diocese of Wessex and then Winchester from 660 to 1093. It stood on a site immediately north of and partially beneath its successor, Winchester Cathedral.

Koenwald or Cenwald or Coenwald was an Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Worcester, probably of Mercian origin.

Æthelwine was ealdorman of East Anglia and one of the leading noblemen in the kingdom of England in the later 10th century. As with his kinsmen, the principal source for his life is Byrhtferth's life of Oswald of Worcester. Æthelwine founded Ramsey Abbey in 969, and Byrhtferth and Ramsey Abbey remembered him as Dei amicus, but the monks of nearby Ely saw him as an enemy who had seized their lands.

Events from the 10th century in the Kingdom of England.

The Liber Eliensis is a 12th-century English chronicle and history, written in Latin. Composed in three books, it was written at Ely Abbey on the island of Ely in the fenlands of eastern Cambridgeshire. Ely Abbey became the cathedral of a newly formed bishopric in 1109. Traditionally the author of the anonymous work has been given as Richard or Thomas, two monks at Ely, one of whom, Richard, has been identified with an official of the monastery, but some historians hold that neither Richard nor Thomas was the author.

The English Benedictine Reform or Monastic Reform of the English church in the late tenth century was a religious and intellectual movement in the later Anglo-Saxon period. In the mid-tenth century almost all monasteries were staffed by secular clergy, who were often married. The reformers sought to replace them with celibate contemplative monks following the Rule of Saint Benedict. The movement was inspired by Continental monastic reforms, and the leading figures were Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury, Æthelwold, Bishop of Winchester, and Oswald, Archbishop of York.

The New Minster Charter is an Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscript that was likely composed by Bishop Æthelwold and presented to the New Minster in Winchester by King Edgar in the year 966 AD to commemorate the Benedictine Reform. It is now part of the British Library's collection.