Ceratophora is a genus of agamid lizards found in Sri Lanka. The male has a horn on its snout.

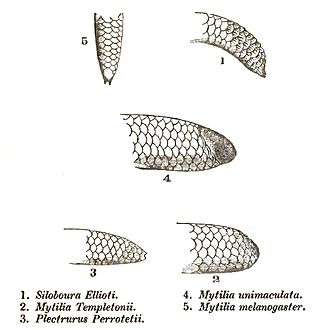

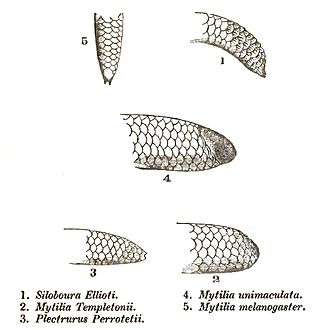

A scute or scutum is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of birds. The term is also used to describe the anterior portion of the mesonotum in insects as well as some arachnids.

Monilesaurus ellioti, also known commonly as Elliot's forest lizard, is a species of arboreal, diurnal, lizard in the family Agamidae. The species is endemic to the Western Ghats, India.

Boiga forsteni, also known commonly as Forsten's cat snake, is a species of mildly venomous rear-fanged snake in the family Colubridae. The species is endemic to South Asia.

Rhabdophis plumbicolor, known as the green keelback or lead keelback, is a species of nonvenomous snake in the family Colubridae native to parts of the Indian subcontinent.

Trachischium guentheri, commonly known as the rosebelly worm-eating snake or Günther's worm-eating snake, is a species of colubrid snake, which is endemic to Asia.

Dopasia gracilis, known commonly as the Asian glass lizard, the Burmese glass lizard, or the Indian glass snake, is a species of legless lizard in the family Anguidae. The species is endemic to Asia.

Eryx conicus, also known as Russell's sand boa, the Common sand boa or the rough-tailed sand boa, is a species of non-venomous snake in the subfamily Erycinae of the family Boidae. The species is native to Southern Asia. No subspecies are recognised.

Uropeltis liura, commonly known as the Ashambu shieldtail and Günther's earth snake, is a species of snake in the family Uropeltidae. The species is endemic to India.

The Indian fringe-fingered lizard, also known commonly as the Indian fringe-toed lizard, is a species of lizard in the family Lacertidae. The species is endemic to Asia.

Ophisops jerdonii, commonly known as Jerdon's cabrita, Jerdon's snake-eye, and the Punjab snake-eyed lacerta, is a species of lizard in the family Lacertidae. The species is native to South Asia.

Ophisops leschenaultii, commonly called Leschenault's snake-eye, Leschenault’s lacerta, or Leschenault's cabrita, is a species of lacertid lizard endemic to India and eastern Sri Lanka. In Sri Lanka, this lizard is called Pandura katussa in Sinhala. In some parts of the country, it is also called Heeraluwa or sikanala, which is more common name for all skink-like reptiles.

Ophiomorus tridactylus, commonly known as the three-toed snake skink, is a species of skink endemic to sandy desert areas of South Asia. It is also called the Indian sand-swimmer for its habit of moving just under the sand.

Jerdon's sea snake is a species of venomous sea snake in the subfamily Hydrophiinae of the family Elapidae. The species is native to the Indian Ocean.

Hydrophis cantoris, also known commonly as Cantor's narrow-headed sea snake and Cantor's small-headed sea snake, is a species of venomous sea snake in the family Elapidae.

Snakes, like other reptiles, have skin covered in scales. Snakes are entirely covered with scales or scutes of various shapes and sizes, known as snakeskin as a whole. A scale protects the body of the snake, aids it in locomotion, allows moisture to be retained within, alters the surface characteristics such as roughness to aid in camouflage, and in some cases even aids in prey capture. The simple or complex colouration patterns are a property of the underlying skin, but the folded nature of scaled skin allows bright skin to be concealed between scales then revealed in order to startle predators.

Snakeskin may either refer to the skin of a live snake, the shed skin of a snake after molting, or to a type of leather that is made from the hide of a dead snake. Snakeskin and scales can have varying patterns and color formations, providing protection via camouflage from predators. The colors and iridescence in these scales are largely determined by the types and amount of chromatophores located in the dermis of the snake skin. The snake's skin and scales are also an important feature to their locomotion, providing protection and minimizing friction when gliding over surfaces.

Rhinophis blythii, or Blyth's earth snake, is a species of snake in the family Uropeltidae. The species is endemic to the rain forests and grasslands of Sri Lanka.

Rhabdophis ceylonensis is endemic to the island of Sri Lanka. The species is commonly known as the Sri Lanka blossom krait, the Sri Lanka keelback, and මල් කරවලා or නිහලුවා (nihaluwa) in Sinhala. It is a moderately venomous snake.

Nessia sarasinorum, commonly known as Sarasins's snake skink or Müller's nessia, is a species of lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is endemic to the island of Sri Lanka.