A quantum mechanical system or particle that is bound—that is, confined spatially—can only take on certain discrete values of energy, called energy levels. This contrasts with classical particles, which can have any amount of energy. The term is commonly used for the energy levels of the electrons in atoms, ions, or molecules, which are bound by the electric field of the nucleus, but can also refer to energy levels of nuclei or vibrational or rotational energy levels in molecules. The energy spectrum of a system with such discrete energy levels is said to be quantized.

Ionization, or Ionisation is the process by which an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge by gaining or losing electrons, often in conjunction with other chemical changes. The resulting electrically charged atom or molecule is called an ion. Ionization can result from the loss of an electron after collisions with subatomic particles, collisions with other atoms, molecules and ions, or through the interaction with electromagnetic radiation. Heterolytic bond cleavage and heterolytic substitution reactions can result in the formation of ion pairs. Ionization can occur through radioactive decay by the internal conversion process, in which an excited nucleus transfers its energy to one of the inner-shell electrons causing it to be ejected.

An excimer is a short-lived dimeric or heterodimeric molecule formed from two species, at least one of which has a valence shell completely filled with electrons. In this case, formation of molecules is possible only if such atom is in an electronic excited state. Heteronuclear molecules and molecules that have more than two species are also called exciplex molecules. Excimers are often diatomic and are composed of two atoms or molecules that would not bond if both were in the ground state. The lifetime of an excimer is very short, on the order of nanoseconds.

The emission spectrum of a chemical element or chemical compound is the spectrum of frequencies of electromagnetic radiation emitted due to an electron making a transition from a high energy state to a lower energy state. The photon energy of the emitted photon is equal to the energy difference between the two states. There are many possible electron transitions for each atom, and each transition has a specific energy difference. This collection of different transitions, leading to different radiated wavelengths, make up an emission spectrum. Each element's emission spectrum is unique. Therefore, spectroscopy can be used to identify elements in matter of unknown composition. Similarly, the emission spectra of molecules can be used in chemical analysis of substances.

Rotational–vibrational spectroscopy is a branch of molecular spectroscopy concerned with infrared and Raman spectra of molecules in the gas phase. Transitions involving changes in both vibrational and rotational states can be abbreviated as rovibrational transitions. When such transitions emit or absorb photons, the frequency is proportional to the difference in energy levels and can be detected by certain kinds of spectroscopy. Since changes in rotational energy levels are typically much smaller than changes in vibrational energy levels, changes in rotational state are said to give fine structure to the vibrational spectrum. For a given vibrational transition, the same theoretical treatment as for pure rotational spectroscopy gives the rotational quantum numbers, energy levels, and selection rules. In linear and spherical top molecules, rotational lines are found as simple progressions at both higher and lower frequencies relative to the pure vibration frequency. In symmetric top molecules the transitions are classified as parallel when the dipole moment change is parallel to the principal axis of rotation, and perpendicular when the change is perpendicular to that axis. The ro-vibrational spectrum of the asymmetric rotor water is important because of the presence of water vapor in the atmosphere.

In quantum mechanics, an excited state of a system is any quantum state of the system that has a higher energy than the ground state. Excitation refers to an increase in energy level above a chosen starting point, usually the ground state, but sometimes an already excited state. The temperature of a group of particles is indicative of the level of excitation.

Vibrational energy relaxation, or vibrational population relaxation, is a process in which the population distribution of molecules in quantum states of high energy level caused by an external perturbation returns to the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution.

Resonance Raman spectroscopy is a Raman spectroscopy technique in which the incident photon energy is close in energy to an electronic transition of a compound or material under examination. The frequency coincidence can lead to greatly enhanced intensity of the Raman scattering, which facilitates the study of chemical compounds present at low concentrations.

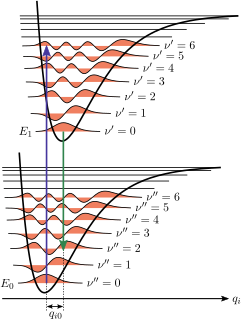

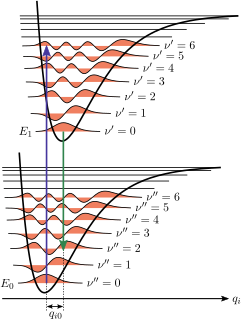

The Franck–Condon principle is a rule in spectroscopy and quantum chemistry that explains the intensity of vibronic transitions. The principle states that during an electronic transition, a change from one vibrational energy level to another will be more likely to happen if the two vibrational wave functions overlap more significantly.

In molecular spectroscopy, a Jablonski diagram is a diagram that illustrates the electronic states and often the vibrational levels of a molecule, and also the transitions between them. The states are arranged vertically by energy and grouped horizontally by spin multiplicity. Nonradiative transitions are indicated by squiggly arrows and radiative transitions by straight arrows. The vibrational ground states of each electronic state are indicated with thick lines, the higher vibrational states with thinner lines. The diagram is named after the Polish physicist Aleksander Jabłoński.

The zero-phonon line and the phonon sideband jointly constitute the line shape of individual light absorbing and emitting molecules (chromophores) embedded into a transparent solid matrix. When the host matrix contains many chromophores, each will contribute a zero-phonon line and a phonon sideband to the absorption and emission spectra. The spectra originating from a collection of identical chromophores in a matrix is said to be inhomogeneously broadened because each chromophore is surrounded by a somewhat different matrix environment which modifies the energy required for an electronic transition. In an inhomogeneous distribution of chromophores, individual zero-phonon line and phonon sideband positions are therefore shifted and overlapping.

The Rydberg states of an atom or molecule are electronically excited states with energies that follow the Rydberg formula as they converge on an ionic state with an ionization energy. Although the Rydberg formula was developed to describe atomic energy levels, it has been used to describe many other systems that have electronic structure roughly similar to atomic hydrogen. In general, at sufficiently high principal quantum numbers, an excited electron-ionic core system will have the general character of a hydrogenic system and the energy levels will follow the Rydberg formula. Rydberg states have energies converging on the energy of the ion. The ionization energy threshold is the energy required to completely liberate an electron from the ionic core of an atom or molecule. In practice, a Rydberg wave packet is created by a laser pulse on a hydrogenic atom and thus populates a superposition of Rydberg states. Modern investigations using pump-probe experiments show molecular pathways – e.g. dissociation of (NO)2 – via these special states.

A molecular vibration is a periodic motion of the atoms of a molecule relative to each other, such that the center of mass of the molecule remains unchanged. The typical vibrational frequencies range from less than 1013 Hz to approximately 1014 Hz, corresponding to wavenumbers of approximately 300 to 3000 cm−1 and wavelengths of approximately 30 to 3 µm.

A Lyman-Werner photon is an ultraviolet photon with a photon energy in the range of 11.2 to 13.6 eV, corresponding to the energy range in which the Lyman and Werner absorption bands of molecular hydrogen (H2) are found. A photon in this energy range, with a frequency that coincides with that of one of the lines in the Lyman or Werner bands, can be absorbed by H2, placing the molecule in an excited electronic state. Radiative decay (that is, decay into photons) from this excited state occurs rapidly, with roughly 15% of these decays occurring into the vibrational continuum of the molecule, resulting in its dissociation. This two-step photodissociation process, known as the Solomon process, is one of the main mechanisms by which molecular hydrogen is destroyed in the interstellar medium.

In vibrational spectroscopy, an overtone band is the spectral band that occurs in a vibrational spectrum of a molecule when the molecule makes a transition from the ground state (v=0) to the second excited state (v=2), where v is the vibrational quantum number obtained from solving the Schrödinger equation for the molecule.

In molecular spectroscopy, the Birge–Sponer method or Birge–Sponer plot is a way to calculate the dissociation energy of a molecule. By observing transitions between as many vibrational energy levels as possible, for example through electronic or infrared spectroscopy, the difference between the energy levels, can be calculated. This sum will have a maximum at , representing the point of bond dissociation; summing over all the differences up to this point gives the total energy required to dissociate the molecule, i.e. to promote it from the ground state to an unbound state. This can be written:

Vibronic spectroscopy is a branch of molecular spectroscopy concerned with vibronic transitions: the simultaneous changes in electronic and vibrational energy levels of a molecule due to the absorption or emission of a photon of the appropriate energy. In the gas phase, vibronic transitions are accompanied by changes in rotational energy also.

Bond softening is an effect of reducing the strength of a chemical bond by strong laser fields. To make this effect significant, the strength of the electric field in the laser light has to be comparable with the electric field the bonding electron "feels" from the nuclei of the molecule. Such fields are typically in the range of 1–10 V/Å, which corresponds to laser intensities 1013–1015 W/cm2. Nowadays, these intensities are routinely achievable from table-top Ti:Sapphire lasers.

The magnesium argide ion, MgAr+ is an ion composed of one ionised magnesium atom, Mg+ and an argon atom. It is important in inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and in the study of the field around the magnesium ion. The ionization potential of magnesium is lower than the first excitation state of argon, so the positive charge in MgAr+ will reside on the magnesium atom. Neutral MgAr molecules can also exist in an excited state.

Diargon or the argon dimer is a molecule containing two argon atoms. Normally, this is only very weakly bound together by van der Waals forces. However, in an excited state, or ionised state, the two atoms can be more tightly bound together, with significant spectral features. At cryogenic temperatures, argon gas can have a few percent of diargon molecules.