Residential school may refer to:

- American Indian boarding schools

- Canadian Indian residential school system

- Boarding school

- Residential treatment center for people with addictions or severe mental illnesses

- Therapeutic boarding school

Residential school may refer to:

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. As they have existed for many centuries, and now extend across many countries, their functioning, codes of conduct and ethos vary greatly. Children in boarding schools study and live during the school year with their fellow students and possibly teachers or administrators. Some boarding schools also have day students who attend the institution during the day and return home in the evenings.

A dormitory, also known as a hall of residence or a residence hall, is a building primarily providing sleeping and residential quarters for large numbers of people such as boarding school, high school, college or university students. In some countries, it can also refer to a room containing several beds accommodating people.

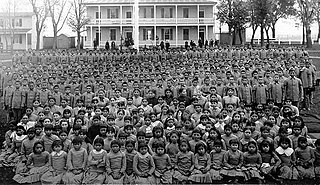

The Canadian Indian residential school system was a network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples. The network was funded by the Canadian government's Department of Indian Affairs and administered by Christian churches. The school system was created to isolate Indigenous children from the influence of their own culture and religion in order to assimilate them into the dominant Canadian culture. Over the course of the system's more than hundred-year existence, around 150,000 children were placed in residential schools nationally. By the 1930s, about 30 percent of Indigenous children were attending residential schools. The number of school-related deaths remains unknown due to incomplete records. Estimates range from 3,200 to over 30,000, mostly from disease.

The Sisters of Charity of Montreal, formerly called The Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général of Montreal and more commonly known as the Grey Nuns of Montreal, is a Canadian religious institute of Roman Catholic religious sisters, founded in 1737 by Marguerite d'Youville, a young widow.

St Hilda's may refer to:

Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools is a 2004 book by the American writer Ward Churchill, then a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and an activist in Native American issues. Beginning in the late 19th century, it traces the history of the United States and Canadian governments establishing Indian boarding schools or residential schools, respectively, where Native American children were required to attend, to encourage their study of English, conversion to Christianity, and assimilation to the majority culture. The boarding schools were operated into the 1980s. Because the schools often prohibited students from using their Native languages and practicing their own cultures, Churchill considers them to have been genocidal in intent.

Nicholas Flood Davin, KC was a lawyer, journalist and politician, born at Kilfinane, Ireland. The first MP for Assiniboia West (1887–1900), Davin was known as the voice of the North-West.

Vital-Justin Grandin was a Roman Catholic priest and bishop labelled as a key architect of the Canadian Indian residential school system by contemporary mainstream and Catholic news sources, which has been considered an instrument of cultural genocide. In June 2021, this led to governments and private businesses to begin removing his name from institutions and infrastructure previously named for him. He served the Church in the western parts of what is now Canada both before and after Confederation. He is also the namesake or co-founder of various small communities and neighbourhoods in what is now Alberta, Canada, especially those of francophone residents.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was a truth and reconciliation commission active in Canada from 2008 to 2015, organized by the parties of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries with a primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilating Native American children and youth into Anglo-American culture. In the process, these schools denigrated Native American culture and made children give up their languages and religion. At the same time the schools provided a basic Western education. These boarding schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations. The missionaries were often approved by the federal government to start both missions and schools on reservations, especially in the lightly populated areas of the West. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries especially, the government paid Church denominations to provide basic education to Native American children on reservations, and later established its own schools on reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also founded additional off-reservation boarding schools. Similarly to schools that taught speakers of immigrant languages, the curriculum was rooted in linguistic imperialism, the English only movement, and forced assimilation enforced by corporal punishment. These sometimes drew children from a variety of tribes. In addition, religious orders established off-reservation schools.

Thomas Indian School, also known as the Thomas Asylum of Orphan and Destitute Indian Children, is a historic school and national historic district located near Irving at the Cattaraugus Indian Reservation in Erie County, New York. The institution was first established in 1855 by missionaries Asher Wright and his wife Laura Wright to house the orphaned and kidnapped Seneca children of the reservation under the federal policy of forced assimilation. The complex was built in about 1900 by New York State as a self-supporting campus. Designed by the New York City firm Barney and Chapman, the campus contains the red brick Georgian Revival style main buildings and a multitude of farm and vocational buildings.

Indian school or Indian School may refer to:

Our Spirits Don't Speak English (2008) is a documentary film about Native American boarding schools attended by young people mostly from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries. It was filmed by the Rich Heape company and directed by Chip Richie. Native American storyteller Gayle Ross narrated the film. Ross is a descendant of John Ross, chief of the Cherokee Nation in the Trail of Tears period.

The Battleford Industrial School was a Canadian Indian residential school for First Nations children in Battleford, Northwest Territories from 1883-1914. It was the first residential school operated by the Government of Canada with the aim of assimilating Indigenous people into the society of the settlers.

The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, originally and still colloquially known as Orange Shirt Day, is a Canadian holiday to recognize the legacy of the Canadian Indian residential school system.

Gordon's Indian Residential School was a boarding school for George Gordon First Nation students in Punnichy, Saskatchewan, and was the last federally-funded residential school in Canada. It was located adjacent to the George Gordon Reserve.

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative was created in June 2021 by Deb Haaland, the United States Secretary of the Interior, to investigate defunct residential boarding schools established under the Civilization Fund Act and that housed Native American children. It is an effort to document known schools and burial grounds, including those with unmarked graves. There will be an attempt to identify and repatriate children's remains to their families or nations.

The Canadian Indian residential school system was a network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples. Directed and funded by the Department of Indian Affairs, and administered mainly by Christian churches, the residential school system removed and isolated Indigenous children from the influence of their own native culture and religion in order to forcefully assimilate them into the dominant Canadian culture. Given that most of them were established by Christian missionaries with the express purpose of converting Indigenous children to Christianity, schools often had nearby mission churches with community cemeteries. Students were often buried in these cemeteries rather than being sent back to their home communities, since the school was expected by the Department of Indian Affairs to keep costs as low as possible. Additionally, occasional outbreaks of disease led to the creation of mass graves when the school had insufficient staff to bury students individually.

The Muscowequan Indian Residential School was a school within the Canadian Indian residential school system that operated on the lands of the Muskowekwan First Nation and in Lestock, Saskatchewan, from 1889 to 1997.