Daniel O'Connell (I) (Irish: Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilization of Catholic Ireland, down to the poorest class of tenant farmers, secured the final installment of Catholic emancipation in 1829 and allowed him to take a seat in the United Kingdom Parliament to which he had been twice elected.

The Irish National Land League was an Irish political organisation of the late 19th century which sought to help poor tenant farmers. Its primary aim was to abolish landlordism in Ireland and enable tenant farmers to own the land they worked on. The period of the Land League's agitation is known as the Land War. Historian R. F. Foster argues that in the countryside the Land League "reinforced the politicization of rural Catholic nationalist Ireland, partly by defining that identity against urbanization, landlordism, Englishness and—implicitly—Protestantism." Foster adds that about a third of the activists were Catholic priests, and Archbishop Thomas Croke was one of its most influential champions.

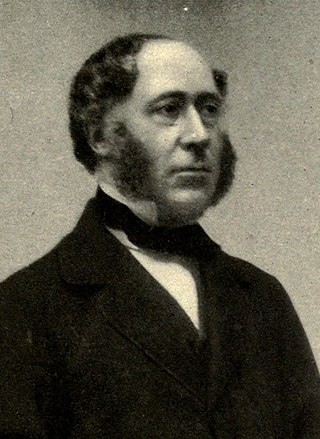

George Henry Moore was an Irish politician, co-founder in the 1850s of the Tenant Right League, of the Catholic Defence Association and, as the Member for Mayo in the United Kingdom Parliament, of the Independent Irish Party. Although an advocate of tenant rights, and renowned for his relief efforts during the Great Famine, at the time of his death in 1870 Moore was defending his rights as a landowner against an oath-bound tenant society, the Ribbonmen.

Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 1801 to 1922. For almost all of this period, the island was governed by the UK Parliament in London through its Dublin Castle administration in Ireland. Ireland underwent considerable difficulties in the 19th century, especially the Great Famine of the 1840s which started a population decline that continued for almost a century. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a vigorous campaign for Irish Home Rule. While legislation enabling Irish Home Rule was eventually passed, militant and armed opposition from Irish unionists, particularly in Ulster, opposed it. Proclamation was shelved for the duration following the outbreak of World War I. By 1918, however, moderate Irish nationalism had been eclipsed by militant republican separatism. In 1919, war broke out between republican separatists and British Government forces. Subsequent negotiations between Sinn Féin, the major Irish party, and the UK government led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which resulted in five-sixths of Ireland seceding from the United Kingdom.

The Whiteboys were a secret Irish agrarian organisation in 18th-century Ireland which defended tenant-farmer land-rights for subsistence farming. Their name derives from the white smocks that members wore in their nighttime raids. Because they levelled fences at night, they were usually called "Levellers" by the authorities, and by themselves "Queen Sive Oultagh's children", "fairies", or followers of "Johanna Meskill" or "Sheila Meskill". They sought to address rack-rents, tithe-collection, excessive priests' dues, evictions, and other oppressive acts. As a result, they targeted landlords and tithe collectors. Over time, Whiteboyism became a general term for rural violence connected to secret societies. Because of this generalization, the historical record for the Whiteboys as a specific organisation is unclear. Three major outbreaks of Whiteboyism occurred: in 1761–1764, 1770–1776, and 1784–1786.

The Twelfth is an Ulster Protestant celebration held on 12 July. It began in the late 18th century in Ulster. It celebrates the Glorious Revolution (1688) and victory of Protestant King William of Orange over Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne (1690), which ensured a Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. On and around the Twelfth, large parades are held by the Orange Order and Ulster loyalist marching bands, streets are bedecked with British flags and bunting, and large towering bonfires are lit in loyalist neighbourhoods. Today the Twelfth is mainly celebrated in Northern Ireland, where it is a public holiday, but smaller celebrations are held in other countries where Orange lodges have been set up.

The Peep o' Day Boys was an agrarian Protestant association in 18th-century Ireland. Originally noted as being an agrarian society around 1779–80, from 1785 it became the Protestant component of the sectarian conflict that emerged in County Armagh, their rivals being the Catholic Defenders. After the Battle of the Diamond in 1795, where an offshoot of the Peep o' Day Boys known as the Orange Boys defeated a force of Defenders, the Orange Order was instituted, and whilst repudiating the activities of the Peep o' Day Boys, they quickly superseded them. The Orange Order would blame the Peep o' Day Boys for "the Armagh outrages" that followed the battle.

The history of Ireland from 1691–1800 was marked by the dominance of the Protestant Ascendancy. These were Anglo-Irish families of the Anglican Church of Ireland, whose English ancestors had settled Ireland in the wake of its conquest by England and colonisation in the Plantations of Ireland, and had taken control of most of the land. Many were absentee landlords based in England, but others lived full-time in Ireland and increasingly identified as Irish.. During this time, Ireland was nominally an autonomous Kingdom with its own Parliament; in actuality it was a client state controlled by the King of Great Britain and supervised by his cabinet in London. The great majority of its population, Roman Catholics, were excluded from power and land ownership under the penal laws. The second-largest group, the Presbyterians in Ulster, owned land and businesses but could not vote and had no political power. The period begins with the defeat of the Catholic Jacobites in the Williamite War in Ireland in 1691 and ends with the Acts of Union 1800, which formally annexed Ireland in a United Kingdom from 1 January 1801 and dissolved the Irish Parliament.

The Defenders were a Catholic agrarian secret society in 18th-century Ireland, founded in County Armagh. Initially, they were formed as local defensive organisations opposed to the Protestant Peep o' Day Boys; however, by 1790 they had become a secret oath-bound fraternal society made up of lodges. By 1796, the Defenders had allied with the United Irishmen, and participated in the 1798 rebellion. By the 19th century, the organisation had developed into the Ribbonmen.

The Land War was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the first and most intense period of agitation between 1879 and 1882, or include later outbreaks of agitation that periodically reignited until 1923, especially the 1886–1891 Plan of Campaign and the 1906–1909 Ranch War. The agitation was led by the Irish National Land League and its successors, the Irish National League and the United Irish League, and aimed to secure fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure for tenant farmers and ultimately peasant proprietorship of the land they worked.

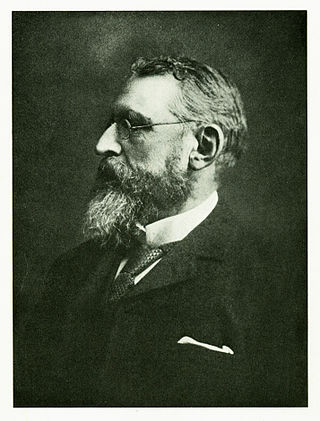

The United Irish League (UIL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland, launched 23 January 1898 with the motto "The Land for the People". Its objective to be achieved through agrarian agitation and land reform, compelling larger grazier farmers to surrender their lands for redistribution among the small tenant farmers. Founded and initiated at Westport, County Mayo by William O'Brien, it was supported by Michael Davitt MP, John Dillon MP, who worded its constitution, Timothy Harrington MP, John O'Connor Power MP and the Catholic clergy of the district. By 1900 it had expanded to be represented by 462 branches in twenty-five counties.

The Hearts of Steel, or Steelboys, was an exclusively Protestant movement originating in 1769 in County Antrim, Ireland due to grievances about the sharp rise of rents and evictions. The protests then spread into the neighbouring counties of Armagh, Down, and Londonderry, before being put down by the army.

Father Nicholas Sheehy (1728–1766) was an 18th-century Irish Roman Catholic priest who was executed on the charge of accessory to murder. Father Sheehy was a prominent and vocal opponent of the Penal Laws, which disenfranchised and persecuted Catholics in Ireland. His conviction is widely regarded as an act of judicial murder amongst supporters of the Irish rebellion.

William Johnston was a unionist politician in Ireland, a Member of Parliament for Belfast, distinguished by his independent working-class following and commitment to reform. He first entered the Westminster Parliament as an Independent Conservative in 1868, celebrated for having broken a standing ban on Orange Order processions and as the nominee of an association of "Protestant Workers". At Westminster, Johnston supported the secret ballot; reforms accommodating of trade unions and strike action; land reform; and woman's suffrage. He was succeeded in 1902 as the MP for South Belfast, by Thomas Sloan, similarly supported by loyalist workers in opposition to the official unionist candidates favoured by their employers.

The Orange Institution, better known as the Orange Order, is a Protestant fraternal organisation based in Northern Ireland. It has been a strong supporter of Irish unionism and has had close links with the Ulster Unionist Party, which governed Northern Ireland from 1922 to 1972. The Institution has lodges throughout Ireland, although it is strongest in the North. There are also branches throughout the British Commonwealth, and in the United States. In the 20th century, the Institution went into sharp decline outside Northern Ireland and County Donegal. Observers have accused the Orange Institution of being a sectarian organisation, due to its goals and its exclusion of Roman Catholics and close relatives of Catholics as members. The Order has a substantial fraternal and benevolent component.

The Burning of Wildgoose Lodge was an arson and murder attack on Wildgoose Lodge, County Louth, Ireland, on the night of 29–30 October 1816, in which eight occupants were killed, including an infant aged five months. The house was near the County Monaghan border, in the townland of Reaghstown, civil parish of Philipstown, barony of Ardee. Eighteen men were executed for the crime, many of them innocent. The event inspired an 1830 short story by William Carleton (1794–1869) and the circumstances have been the subject of historical and political debate.

The Hearts of Oak, also known as Oakboys and Greenboys, was a protest movement of farmers and weavers that arose in County Armagh, Ireland in 1761. Their grievances were the paying of ever increasing county cess, tithes, and small dues. The Hearts of Oak name came from the wearing of a piece of oak in their hats. By the end of the protests the movement had spread to the neighbouring counties of Cavan, Fermanagh, Londonderry, Monaghan, and Tyrone.

Protestantism is a Christian minority on the island of Ireland. In the 2011 census of Northern Ireland, 48% (883,768) described themselves as Protestant, which was a decline of approximately 50% from the 2001 census. In the 2011 census of the Republic of Ireland, 4.27% of the population described themselves as Protestant. In the Republic, Protestantism was the second largest religious grouping until the 2002 census in which they were exceeded by those who chose "No Religion". Some forms of Protestantism existed in Ireland in the early 16th century before the English Reformation, but demographically speaking these were very insignificant and the real influx of Protestantism began only with the spread of the English Reformation to Ireland. The Church of Ireland was established by King Henry VIII of England, who had himself proclaimed as King of Ireland.

Captain Rock was a mythical Irish folk hero, and the name used for the agrarian rebel group he represented in the south-west of Ireland from 1821 to 1824.

Alternative legal systems began to be used by Irish nationalist organizations during the 1760s as a means of opposing British rule in Ireland. Groups which enforced different laws included the Whiteboys, Repeal Association, Ribbonmen, Irish National Land League, Irish National League, United Irish League, Sinn Féin, and the Irish Republic during the Irish War of Independence. These alternative justice systems were connected to the agrarian protest movements which sponsored them and filled the gap left by the official authority, which never had the popular support or legitimacy which it needed to govern effectively. Opponents of British rule in Ireland sought to create an alternative system, based on Irish law, which would eventually supplant British authority.