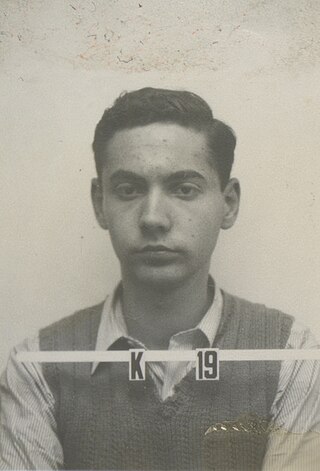

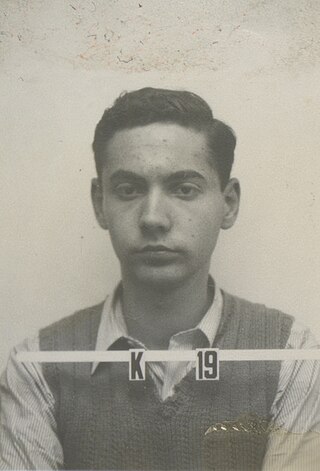

Theodore Alvin Hall was an American physicist and an atomic spy for the Soviet Union, who, during his work on United States efforts to develop the first and second atomic bombs during World War II, gave a detailed description of the "Fat Man" plutonium bomb, and of several processes for purifying plutonium, to Soviet intelligence.

Cold War espionage describes the intelligence gathering activities during the Cold War between the Western allies and the Eastern Bloc. Both relied on a wide variety of military and civilian agencies in this pursuit.

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service and later absorbed by the National Security Agency (NSA), that ran from February 1, 1943, until October 1, 1980. It was intended to decrypt messages transmitted by the intelligence agencies of the Soviet Union. Initiated when the Soviet Union was an ally of the US, the program continued during the Cold War, when the Soviet Union was considered an enemy.

Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg were an American married couple who were convicted of spying for the Soviet Union, including providing top-secret information about American radar, sonar, jet propulsion engines, and nuclear weapon designs. Convicted of espionage in 1951, they were executed by the federal government of the United States in 1953 at Sing Sing in Ossining, New York, becoming the first American civilians to be executed for such charges and the first to be executed during peacetime. Other convicted co-conspirators were sentenced to prison, including Ethel's brother, David Greenglass, Harry Gold, and Morton Sobell. Klaus Fuchs, a German scientist working in Los Alamos, was convicted in the United Kingdom.

David Greenglass was an American machinist and atomic spy for the Soviet Union who worked on the Manhattan Project. He was briefly stationed at the Clinton Engineer Works uranium enrichment facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and then worked at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico from August 1944 until February 1946.

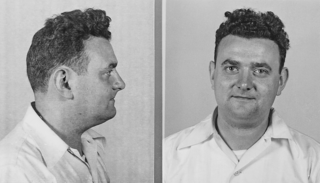

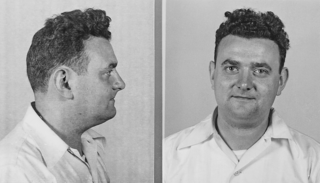

Harry Gold was a Swiss-born American laboratory chemist who was convicted as a courier for the Soviet Union passing atomic secrets from Klaus Fuchs, an agent of the Soviet Union, during World War II. Gold served as a government witness and testified in the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were convicted and executed in 1953 for their roles. Gold served 15 years in prison.

Judith Coplon Socolov was a spy for the Soviet Union whose trials, convictions, and successful constitutional appeals had a profound influence on espionage prosecutions during the Cold War.

As early as the 1920s, the Soviet Union, through its GRU, OGPU, NKVD, and KGB intelligence agencies, used Russian and foreign-born nationals, as well as Communists of American origin, to perform espionage activities in the United States, forming various spy rings. Particularly during the 1940s, some of these espionage networks had contact with various U.S. government agencies. These Soviet espionage networks illegally transmitted confidential information to Moscow, such as information on the development of the atomic bomb. Soviet spies also participated in propaganda and disinformation operations, known as active measures, and attempted to sabotage diplomatic relationships between the U.S. and its allies.

Maurice Hyman Halperin (1906–1995) was an American writer, professor, diplomat, and accused Soviet spy.

Perseus was the code name of a hypothetical Soviet atomic spy that, if real, would have allegedly breached United States national security by infiltrating Los Alamos National Laboratory during the development of the Manhattan Project, and consequently, would have been instrumental for the Soviets in the development of nuclear weapons.

Alfred Epaminondas Sarant, also known as Filipp Georgievich Staros and Philip Georgievich Staros, was an engineer and a member of the Communist party in New York City in 1944. He was part of the Rosenberg spy ring that reported to Soviet intelligence. Sarant worked on secret military radar at the United States Army Signal Corps laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Alexandre Feklisov, one of the KGB case officers who handled the Rosenberg spy apparatus described Sarant and Joel Barr as among the most productive members of the group. Sarant was recruited as a Soviet espionage agent by Barr.

Joel Barr, also Iozef Veniaminovich Berg and Joseph Berg, was part of the Soviet Atomic Spy Ring.

Anatoly Antonovich Yatskov, also known as Anatoli Yatzkov – was a Soviet consul in New York as well as an NKVD foreign intelligence officer handling American agents and couriers linked to the U.S. Manhattan Project during WWII. His spy cover was eventually blown by the U.S. Army Venona Program which identified him as a key NKVD spymaster involved in the 1940s Atomic Spy Ring.

Harry Magdoff was accused by a number of authors as having been complicit in Soviet espionage activity during his time in US government. He was accused of passing information to Soviet intelligence networks in the United States, primarily through what the FBI called the "Perlo Group." Magdoff was never indicted, but after the end of the Cold War, a number of scholars have inspected declassified documents from U.S. and Soviet archives. They cite these documents to support the claim that Magdoff was involved in espionage. Other authors have taken issue with some of the broader interpretations of such materials which implicate many Americans in espionage for the Soviet Union, and the allegation that Harry Magdoff was an information source for the Soviets is disputed by several academics and historians asserting that Magdoff probably had no malicious intentions and committed no crimes.

Ignacy Witczak was a GRU illegal officer in the United States during World War II.

Leonid Romanovich Kvasnikov was a Soviet and Russian chemical engineer and a spy, serving first in NKVD and later served in KGB. Graduated with honors from the Moscow Institute of Chemical Machine-Building in 1934 and worked as an engineer in a chemical plant for several years in the Tula region. Kvasnikov continued postgraduate engineering studies and joined the KGB in 1938 as a specialist in scientific-technical intelligence. Beginning in 1939 he was the section head of scientific and technical intelligence. Kvasnikov served a few short-term assignments in Germany and Poland and rising swiftly to become deputy chief and then chief of the KGB scientific intelligence section.

Haik Badalovich Ovakimian, Major General, USSR, better known as "the puppetmaster" in intelligence circles, was a leading Soviet NKVD spy in the United States.

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early Cold War. Exactly what was given, and whether everyone on the list gave it, are still matters of some scholarly dispute. In some cases, some of the arrested suspects or government witnesses had given strong testimonies or confessions which they recanted later or said were fabricated. Their work constitutes the most publicly well-known and well-documented case of nuclear espionage in the history of nuclear weapons. At the same time, numerous nuclear scientists wanted to share the information with the world scientific community, but this proposal was firmly quashed by the United States government. It is worth noting that many scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project were deeply conflicted about the ethical implications of their work, and some were actively opposed to the use of nuclear weapons.