Related Research Articles

Longitude is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter lambda (λ). Meridians are imaginary semicircular lines running from pole to pole that connect points with the same longitude. The prime meridian defines 0° longitude; by convention the International Reference Meridian for the Earth passes near the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, south-east London on the island of Great Britain. Positive longitudes are east of the prime meridian, and negative ones are west.

Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, formerly sometimes spelled de la Caille, was a French astronomer and geodesist who named 14 out of the 88 constellations. From 1750 to 1754, he studied the sky at the Cape of Good Hope in present-day South Africa. Lacaille observed over 10,000 stars using a refracting telescope.

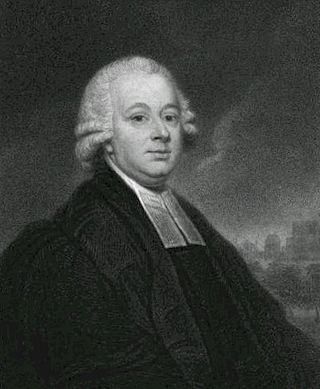

Nevil Maskelyne was the fifth British Astronomer Royal. He held the office from 1765 to 1811. He was the first person to scientifically measure the mass of the planet Earth. He created The Nautical Almanac, in full the British Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris for the Meridian of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich using Tobias Mayer's corrections for Euler's Lunar Theory tables.

Charles Mason was an English-American astronomer who made significant contributions to 18th-century science and American history, particularly through his survey with Jeremiah Dixon of the Mason–Dixon line, which came to mark the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania (1764–1768). The border between Delaware and Maryland is also defined by a part of the Mason–Dixon line.

Jeremiah Dixon was an English surveyor and astronomer who is best known for his work with Charles Mason, from 1763 to 1767, in determining what was later called the Mason–Dixon line.

Nathaniel Bliss was an English astronomer of the 18th century, serving as Britain's fourth Astronomer Royal between 1762 and 1764.

The year 1767 in science and technology involved some significant events.

A transit of Venus takes place when Venus passes directly between the Sun and the Earth, becoming visible against the solar disk. During a transit, Venus is visible as a small black circle moving across the face of the Sun.

Charles Green was a British astronomer, noted for his assignment by the Royal Society in 1768 to the expedition sent to the Pacific Ocean in order to observe the transit of Venus aboard James Cook's Endeavour.

Vice-Admiral John Campbell (1720–1790) was born in the parish of Kirkbean in Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland. Campbell was a British naval officer, navigational expert and colonial governor.

In celestial navigation, lunar distance, also called a lunar, is the angular distance between the Moon and another celestial body. The lunar distances method uses this angle and a nautical almanac to calculate Greenwich time if so desired, or by extension any other time. That calculated time can be used in solving a spherical triangle. The theory was first published by Johannes Werner in 1524, before the necessary almanacs had been published. A fuller method was published in 1763 and used until about 1850 when it was superseded by the marine chronometer. A similar method uses the positions of the Galilean moons of Jupiter.

Richard Dunthorne was an English astronomer and surveyor, who worked in Cambridge as astronomical and scientific assistant to Roger Long, and also concurrently for many years as surveyor to the Bedford Level Corporation.

The history of longitude describes the centuries-long effort by astronomers, cartographers and navigators to discover a means of determining the longitude of any given place on Earth. The measurement of longitude is important to both cartography and navigation. In particular, for safe ocean navigation, knowledge of both latitude and longitude is required, however latitude can be determined with good accuracy with local astronomical observations.

William Wales was a British mathematician and astronomer who sailed on Captain Cook's second voyage of discovery, then became Master of the Royal Mathematical School at Christ's Hospital and a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Reuben Burrow was an English mathematician, surveyor and orientalist. Initially a teacher, he was appointed assistant to Sir Nevil Maskelyne, the fifth Astronomer Royal, at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, and was involved in the Schiehallion experiment. He later conducted research in India, teaching himself Sanskrit and becoming one of the first members of the Asiatic Society. He was the first to measure the length of a degree of an arc of longitude along the Tropic of Cancer. His other major achievements included a study of Indian mathematics, although he earned a reputation for being rude and unpolished amid the leading figures in science who came mostly from the upper-class. One commentator called him "an able mathematician but a most vulgar and scurrilous dog."

William Lax was an English astronomer and mathematician who served as Lowndean Professor of Astronomy and Geometry at the University of Cambridge for 41 years.

William Bayly (1737–1810) was an English astronomer.

Samuel Dunn (1723–1794) was a British mathematician, teacher, cartographer and amateur astronomer.

Mary Edwards was a human computer for the British Nautical Almanac and one of a very few women paid directly by the Board of Longitude, and to earn a living from scientific work at the time.

John Crosley (1762–1817) was an English astronomer and mathematician who was an assistant at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, a computer of the Nautical Almanac, an observer on maritime voyages of scientific exploration and a member and President of the Spitalfields Mathematical Society.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bennett, Jim (2014). "'The Rev. Mr. Nevil Maskelyne, F.R.S. and Myself': The Story of Robert Waddington". Maskelyne: Astronomer Royal. London: Robert Hale Ltd: 59–88.

- 1 2 Waddington, Robert (1763). A Practical Method for Finding the Longitude and Latitude of a Ship at Sea, by Observations of the Moon. London: W. Richardson and S. Clark.

- ↑ "Catalogue of the Royal Astronomical Society archives" . Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ Janisch, Hudson Ralph (1885). Extracts from the St. Helena Records. St. Helena. p. 195.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Maskelyne, Nevil. "Journal of voyage to St Helena". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ Maskelyne, Nevil (1763). The British Mariner's Guide. London.

- ↑ "Confirmed Minutes of the Board of Longitude, 1737-1779". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ Waddington, Robert (1777). Rob. Waddington's Epitome of Theoretical and Practical Navigation. London.

- ↑ "Books: Natural History, Medicine, Mathematics, &c". The Edinburgh Magazine and Literary Miscellany. 40: 501. 1778. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ "Will of Robert Waddington of Westminster, Middlesex". The National Archives. Retrieved 2 May 2015.