Related Research Articles

The First Punic War was the first of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and greatest naval war of antiquity, the two powers struggled for supremacy. The war was fought primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters, and also in North Africa. After immense losses on both sides, the Carthaginians were defeated.

The Punic Wars were a series of wars between 264 and 146 BC fought between Rome and Carthage. Three conflicts between these states took place on both land and sea across the western Mediterranean region and involved a total of forty-three years of warfare. The Punic Wars are also considered to include the four-year-long revolt against Carthage which started in 241 BC. Each war involved immense materiel and human losses on both sides.

Polybius was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work The Histories, a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 BC, recording in detail events in Italy, Iberia, Greece, Macedonia, Syria, Egypt and Africa, and documented the Punic Wars and Macedonian Wars among many others.

The Second Punic War was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Italy and Iberia, but also on the islands of Sicily and Sardinia and, towards the end of the war, in North Africa. After immense materiel and human losses on both sides, the Carthaginians were once again defeated. Macedonia, Syracuse and several Numidian kingdoms were drawn into the fighting, and Iberian and Gallic forces fought on both sides. There were three main military theatres during the war: Italy, where Hannibal defeated the Roman legions repeatedly, with occasional subsidiary campaigns in Sicily, Sardinia and Greece; Iberia, where Hasdrubal, a younger brother of Hannibal, defended the Carthaginian colonial cities with mixed success before moving into Italy; and Africa, where Rome finally won the war.

The Third Punic War was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between Carthage and Rome. The war was fought entirely within Carthaginian territory, in what is now northern Tunisia. When the Second Punic War ended in 201 BC one of the terms of the peace treaty prohibited Carthage from waging war without Rome's permission. Rome's ally, King Masinissa of Numidia, exploited this to repeatedly raid and seize Carthaginian territory with impunity. In 149 BC Carthage sent an army, under Hasdrubal, against Masinissa, the treaty notwithstanding. The campaign ended in disaster as the Battle of Oroscopa ended with a Carthaginian defeat and the surrender of the Carthaginian army. Anti-Carthaginian factions in Rome used the illicit military action as a pretext to prepare a punitive expedition.

The Battle of Zama was fought in 202 BC in what is now Tunisia between a Roman army commanded by Scipio Africanus and a Carthaginian army commanded by Hannibal. The battle was part of the Second Punic War and resulted in such a severe defeat for the Carthaginians that they capitulated, while Hannibal was forced into exile. Roman army of approximately 30,000 men was outnumbered by the Carthaginians who fielded either 40,000 or 50,000; the Romans were stronger in cavalry, but the Carthaginians had 80 war elephants.

The siege of Carthage was the main engagement of the Third Punic War fought between Carthage and Rome. It consisted of the nearly-three-year siege of the Carthaginian capital, Carthage. In 149 BC, a large Roman army landed at Utica in North Africa. The Carthaginians hoped to appease the Romans, but despite the Carthaginians surrendering all of their weapons, the Romans pressed on to besiege the city of Carthage. The Roman campaign suffered repeated setbacks through 149 BC, only alleviated by Scipio Aemilianus, a middle-ranking officer, distinguishing himself several times. A new Roman commander took over in 148 BC, and fared equally badly. At the annual election of Roman magistrates in early 147 BC, the public support for Scipio was so great that the usual age restrictions were lifted to allow him to be appointed commander in Africa.

The Battle of the Lipari Islands or Battle of Lipara was a naval encounter fought in 260 BC during the First Punic War. A squadron of 20 Carthaginian ships commanded by Boödes surprised 17 Roman ships under the senior consul for the year Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio in Lipara Harbour. The inexperienced Romans made a poor showing, with all 17 of their ships captured, along with their commander.

The Battle of Mylae took place in 260 BC during the First Punic War and was the first real naval battle between Carthage and the Roman Republic. This battle was key in the Roman victory of Mylae as well as Sicily itself. It also marked Rome's first naval triumph and also the first use of the corvus in battle.

The Battle of Cape Ecnomus or Eknomos was a naval battle, fought off southern Sicily, in 256 BC, between the fleets of Carthage and the Roman Republic, during the First Punic War. The Carthaginian fleet was commanded by Hanno and Hamilcar; the Roman fleet jointly by the consuls for the year, Marcus Atilius Regulus and Lucius Manlius Vulso Longus. It resulted in a clear victory for the Romans.

The naval Battle of Drepana took place in 249 BC during the First Punic War near Drepana in western Sicily, between a Carthaginian fleet under Adherbal and a Roman fleet commanded by Publius Claudius Pulcher.

The Battle of the Aegates was a naval battle fought on 10 March 241 BC between the fleets of Carthage and Rome during the First Punic War. It took place among the Aegates Islands, off the western coast of the island of Sicily. The Carthaginians were commanded by Hanno, and the Romans were under the overall authority of Gaius Lutatius Catulus, but Quintus Valerius Falto commanded during the battle. It was the final and deciding battle of the 23-year-long First Punic War.

Gravitas was one of the ancient Roman virtues that denoted "seriousness". It is also translated variously as weight, dignity, and importance and connotes restraint and moral rigor. It also conveys a sense of responsibility and commitment to the task.

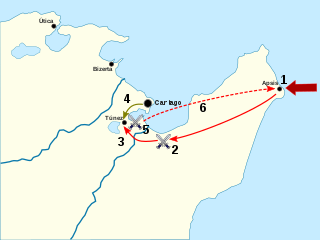

The Battle of the Bagradas River, also known as the Battle of Tunis, was a victory by a Carthaginian army led by Xanthippus over a Roman army led by Marcus Atilius Regulus in the spring of 255 BC, nine years into the First Punic War. The previous year, the newly constructed Roman navy established naval superiority over Carthage. The Romans used this advantage to invade Carthage's homeland, which roughly aligned with modern-day Tunisia in North Africa. After landing on the Cape Bon Peninsula and conducting a successful campaign, the fleet returned to Sicily, leaving Regulus with 15,500 men to hold the lodgement in Africa over the winter.

The battle of Adys took place in late 256 BC during the First Punic War between a Carthaginian army jointly commanded by Bostar, Hamilcar and Hasdrubal and a Roman army led by Marcus Atilius Regulus. Earlier in the year, the new Roman navy had established naval superiority and used this advantage to invade the Carthaginian homeland, which roughly aligned with modern Tunisia in North Africa. After landing on the Cape Bon Peninsula and conducting a successful campaign, the fleet returned to Sicily, leaving Regulus with 15,500 men to hold the lodgement in Africa over the winter.

The Battle of Panormus was fought in Sicily in 250 BC during the First Punic War between a Roman army led by Lucius Caecilius Metellus and a Carthaginian force led by Hasdrubal, son of Hanno. The Roman force of two Roman and two allied legions defending the city of Panormus defeated the much larger Carthaginian army of 30,000 men and between 60 and 142 war elephants.

The Treaty of Lutatius was the agreement between Carthage and Rome of 241 BC, that ended the First Punic War after 23 years of conflict. Most of the fighting during the war took place on, or in the waters around, the island of Sicily and in 241 BC a Carthaginian fleet was defeated by a Roman fleet commanded by Gaius Lutatius Catulus while attempting to lift the blockade of its last, beleaguered, strongholds there. Accepting defeat, the Carthaginian Senate ordered their army commander on Sicily, Hamilcar Barca, to negotiate a peace treaty with the Romans, on whatever terms he could negotiate. Hamilcar refused, claiming the surrender was unnecessary, and the negotiation of the peace terms was left to Gisco, the commander of Lilybaeum, as the next most senior Carthaginian on the island. A draft treaty was rapidly agreed upon, but when it was referred to Rome for ratification it was rejected.

Ancient Carthage was an ancient Semitic civilisation based in North Africa. Initially a settlement in present-day Tunisia, it later became a city-state and then an empire. Founded by the Phoenicians in the ninth century BC, Carthage reached its height in the fourth century BC as one of the largest metropolises in the world. It was the centre of the Carthaginian Empire, a major power led by the Punic people who dominated the ancient western and central Mediterranean Sea. Following the Punic Wars, Carthage was destroyed by the Romans in 146 BC, who later rebuilt the city lavishly.

The siege of Lilybaeum lasted for nine years, from 250 to 241 BC, as the Roman army laid siege to the Carthaginian-held Sicilian city of Lilybaeum during the First Punic War. Rome and Carthage had been at war since 264 BC, fighting mostly on the island of Sicily or in the waters around it, and the Romans were slowly pushing the Carthaginians back. By 250 BC, the Carthaginians held only the cities of Lilybaeum and Drepana; these were well-fortified and situated on the west coast, where they could be supplied and reinforced by sea without the Romans being able to use their superior army to interfere.

The Roman withdrawal from Africa was the attempt by the Roman Republic in 255 BC to rescue the survivors of their defeated expeditionary force to Carthaginian Africa during the First Punic War. A large fleet commanded by Servius Fulvius Paetinus Nobilior and Marcus Aemilius Paullus successfully evacuated the survivors after defeating an intercepting Carthaginian fleet, but was struck by a storm while returning, losing most of its ships.

References

- ↑ Merrills, Andrew; Miles, Richard (2010). The Vandals (The Peoples of Europe). p. 88. ISBN 978-1405160681 . Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ↑ Gazda, Elaine K. (2002). The Ancient Art of Emulation: Studies in Artistic Originality and Tradition from the Present to Classical Antiquity. p. 4. ISBN 978-0472111893 . Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ↑ Fouracre, Paul (2005). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 1, c.500-c.700. p. 40. ISBN 978-0521362917 . Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- 1 2 Winter, Bruce W. (2003). Roman Wives, Roman Widows: The Appearance of New Women and the Pauline Communities. p. 5, note 11. ISBN 978-0802849717 . Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- 1 2 Green, Bernard (2010). Christianity in Rome in the First Three Centuries. p. 129. ISBN 978-0567032508 . Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ↑ Woolf, Greg (2000). Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul. p. 120. ISBN 978-0521789820.

- ↑ Wilhite, David E. (2007). Tertullian the African: An Anthropological Reading of Tertullian's Context and Identities. p. 42. ISBN 978-3110194531 . Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ↑ SILVA, A. J. M. 2012, From lost Roman pottery to broken identities in Post-modern times: on the use of the concept of identity in Roman Archaeology, 28th Congress of the Rei Cretariae Romanae Fautores, Catania. https://www.academia.edu/1994803/From_lost_Roman_pottery_to_broken_identities_in_Post-modern_times_on_the_use_of_the_concept_of_identity_in_Roman_Archaeology

- 1 2 Polibius, Histories 6.56 http://www.gutenberg.org/files/44125/44125-h/44125-h.htm#b6_56

- ↑ "Historian on the Edge: Transformations of Romanness". 27 October 2013.

- ↑ James, ‘Gregory of Tours and the Franks’, p.66. James (p.60) says that Gregory writes of the identities ‘Frank’ and ‘Arvernian’ ‘as if they were equivalent ethnic terms’.