Related Research Articles

Lionel George Curtis CH (1872–1955) was a British internationalist and author. He was the inspiration for the foundation of Chatham House as well as the US Council On Foreign Relations at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. He was a leading member of Round Table movement. His writings and influence caused the evolution of the former British nations into the Commonwealth.

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom's minister in charge of managing the British Empire.

Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery, also known as L. S. Amery, was a British Conservative politician and journalist. During his career, he was known for his interest in military preparedness, British India and the British Empire and for his opposition to appeasement. After his retirement and death, he was perhaps best known for the remarks he made in the House of Commons on 7 May 1940 during the Norway Debate.

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a very important role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and early 1920s. From December 1916 to November 1918, he was one of the most important members of Prime Minister David Lloyd George's War cabinet.

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

George Geoffrey Dawson was editor of The Times from 1912 to 1919 and again from 1923 until 1941. His original last name was Robinson, but he changed it in 1917. He married Hon. Margaret Cecilia Lawley, daughter of Arthur Lawley, 6th Baron Wenlock, in 1919.

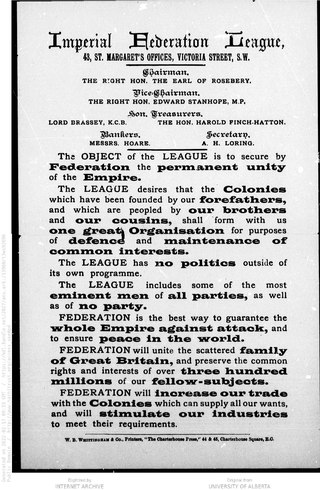

The Imperial Federation was a series of proposals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to create a federal union to replace the existing British Empire, presenting it as an alternative to colonial imperialism. No such proposal was ever adopted, but various schemes were popular in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and other colonial territories. The project was championed by Unionists such as Joseph Chamberlain as an alternative to William Gladstone's proposals for home rule in Ireland.

Carroll Quigley was an American historian and theorist of the evolution of civilizations. He is remembered for his teaching work as a professor at Georgetown University, and his seminal works, The Evolution of Civilizations: An Introduction to Historical Analysis, and Tragedy And Hope; A History Of The World In Our Time, in which he states that an Anglo-American banking elite have worked together for centuries to spread certain values globally.

The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs is an international relations journal established in 1910 relating to the Commonwealth of Nations.

Milner's Kindergarten is the informal name of a group of Britons who served in the South African civil service under High Commissioner Alfred, Lord Milner, between the Second Boer War and the founding of the Union of South Africa in 1910. It is possible that the kindergarten was Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain's idea, for in his diary dated 14 August 1901, Chamberlain's assistant secretary Geoffrey Robinson wrote, "Another long day occupied chiefly in getting together a list of South African candidates for Lord Milner – from people already in the (Civil) Service". They were in favour of the unification of South Africa and, ultimately, an Imperial Federation with the British Empire itself. On Milner's retirement, most continued in the service under Lord Selborne, who was Milner's successor, and the number two-man at the Colonial Office. The Kindergarten started off with 12 men, most of whom were Oxford graduates and English civil servants, who made the trip to South Africa in 1901 to help Lord Milner rebuild the war torn economy. Quite young and inexperienced, one of them brought with him a biography written by F.S. Oliver on Alexander Hamilton. He read the book, and the plan for rebuilding the new government of South Africa was based along the lines of the book, Hamilton's federalist philosophy, and his knowledge of treasury operations. The name, "Milner's Kindergarten", although first used derisively by Sir William Thackeray Marriott, was adopted by the group as its name.

A ginger group is a formal or informal group within an organisation seeking to influence its direction and activity. The term comes from the phrase ginger up, meaning to enliven or stimulate. Ginger groups work to alter the organisation's policies, practices, or office-holders, while still supporting its general goals. Ginger groups sometimes form within the political parties of Commonwealth countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and Pakistan.

Jerome Davis Greene was an American banker and a trustee to several major organizations and trusts including the Brookings Institution and the Rockefeller Foundation.

James Scorgie Meston, 1st Baron Meston, was a prominent British civil servant, financial expert and businessman. He served as Lieutenant-Governor of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh from 1912 to 1918.

The Imperial Federation League was a 19th-century organisation which aimed to promote the reorganisation of the British Empire into an Imperial Federation, similarly to the way the majority of British North America confederated into the Dominion of Canada in the mid-19th century. The League promoted the closer union of the British Empire and advocated the establishment of "representative government" for the UK, Canada and the self-governing colonies of 'Australasia' and Cape Colony within a single state.

Sir Alfred Eckhard Zimmern was an English classical scholar, historian, and political scientist writing on international relations. A British policymaker during World War I and a prominent liberal thinker, Zimmern played an important role in drafting the blueprint for what would become the League of Nations.

Sir Reginald Coupland was an English historian of the British Empire. Between 1920 and 1948, he held the Beit Professorship of Colonial History at the University of Oxford.

Frederick Scott Oliver, known as F. S. Oliver, was a prominent Scottish political writer and businessman who advocated tariff reform and imperial union for the British Empire. He played an important role in the Round Table movement, collaborated in the downfall of Prime Minister H. H. Asquith's wartime government and its replacement by David Lloyd George in 1916, and pressed for "home rule all round" to resolve the political conflict between Britain and Irish nationalists.

Rhodes House is a building part of the University of Oxford in England. It is located on South Parks Road in central Oxford, and was built in memory of Cecil Rhodes, an alumnus of the university and a major benefactor. It is listed Grade II* on the National Heritage List for England.

The War Policy Committee was a small group of British ministers, most of them members of the War Cabinet, set up during World War I to decide war strategy. The committee was created at the request of Lord Milner on 7 June 1917, through a memorandum he circulated with his peers on the British War Cabinet. Its members included the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, Lord Milner, Edward Carson, Lord Curzon and Jan Smuts. The committee was formed to discuss the strategic matter of the Russian Revolution, and the new entry of The United States. Coincidentally or not, the timing of Lord Milner's memo coincided with the detonation of 19 underground mines filled with explosives on the Western Front, which created the largest human explosion of all time. The night before this explosion, General Harington said to reporters "Gentleman, I don't know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change the geography". In Milner's memo, he stressed that the allies must act together for the common good, and not devolve to piecemeal arrangements that satisfied specific countries. The War Policy Committee was formed, and it discussed every major initiative taken by the allies until the end of the war. It was chaired by Lord's Milner and Curzon, with Jan Smuts as its Vice Chairman.

The Monday Night Cabal was a 'ginger group' of influential people set up in London by Leo Amery at the start of 1916 to discuss war policy. The nucleus of the group consisted of Lord Milner, George Carson, Geoffrey Dawson, Waldorf Astor and F. S. Oliver. The group got together for Monday night dinners and to discuss politics. Throughout 1916 their numbers and influence grew to include Minister of Munitions David Lloyd George, General Henry Wilson, Philip Kerr, and Mark Jameson. It is thought that word of the Ginger Group reached Douglas Haig, prompting him to invite Lord Milner to France in November for an 8-day tour of the Western Front. It was through the Ginger Group that Times editor Geoffrey Dawson published a December 4, 1916 news story titled "Reconstruction" that set in motion events that caused Prime Minister H. H. Asquith to resign, signaling the rise of the Lloyd George Ministry. Among the group's primary objectives was the formation of a small war cabinet within government to fight the war against the German Empire effectively. This point was advanced by The Times as early as April 1915, so it is unknown if the Ginger Group, or one its predecessor elements was responsible for the idea behind Lloyd George's decision to create a War Cabinet on the day he was appointed prime minister. However, his surprise choice of Lord Milner as one of the War Cabinet's five members shows the influence of the ginger group on him.

References

- ↑ Marlowe, Milner, Apostle of Empire, pp. 206–207

- ↑ Olson, James Stuart; Shadle, Robert (1996). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. ISBN 0-313-27917-9.

- ↑ J. Lee Thompson (2007). Forgotten Patriot: A Life of Alfred, Viscount Milner of St. James's And Cape Town, 1854–1925. ISBN 978-0-8386-4121-7.

- ↑ May, Alexander The Round Table, 1910–66 DPhil. University of Oxford 1995 pp. 69–72

- ↑ White Australia The Round Table Volume 11, 1921

- ↑ Roskill, Stephen, Hankey: Man of Secrets, Vol. I, pp. 422–423

- ↑ Thompson, J. Lee, Forgotten Patriot, p.. 370

- ↑ The Journal's History

- ↑ May, Alexander The Round Table, 1910–66 DPhil. University of Oxford (1995) Appendix B pp. 451–453

- ↑ Quigley, Carroll : Tragedy & Hope: A History of the World in Our Time. G. S. G. & Associates, Incorporated (June 1975). ISBN 0-945001-10-X, ISBN 978-0-945001-10-2

- ↑ Conspiracy Encyclopedia Collins & Brown (2005) p. 179

- ↑ May, Alexander The Round Table, 1910–66 DPhil. University of Oxford (1995) pp. 16–17

- ↑ David P. Billington Jr Tragedy and Hope: Carroll Quigley and the 'Rhodes Conspiracy The American Oxonian 82/4 1994 p. 232