Related Research Articles

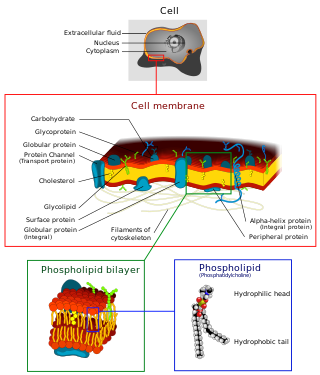

A biological membrane, biomembrane or cell membrane is a selectively permeable membrane that separates the interior of a cell from the external environment or creates intracellular compartments by serving as a boundary between one part of the cell and another. Biological membranes, in the form of eukaryotic cell membranes, consist of a phospholipid bilayer with embedded, integral and peripheral proteins used in communication and transportation of chemicals and ions. The bulk of lipids in a cell membrane provides a fluid matrix for proteins to rotate and laterally diffuse for physiological functioning. Proteins are adapted to high membrane fluidity environment of the lipid bilayer with the presence of an annular lipid shell, consisting of lipid molecules bound tightly to the surface of integral membrane proteins. The cell membranes are different from the isolating tissues formed by layers of cells, such as mucous membranes, basement membranes, and serous membranes.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a part of a transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER). The endoplasmic reticulum is found in most eukaryotic cells and forms an interconnected network of flattened, membrane-enclosed sacs known as cisternae, and tubular structures in the SER. The membranes of the ER are continuous with the outer nuclear membrane. The endoplasmic reticulum is not found in red blood cells, or spermatozoa.

The endomembrane system is composed of the different membranes (endomembranes) that are suspended in the cytoplasm within a eukaryotic cell. These membranes divide the cell into functional and structural compartments, or organelles. In eukaryotes the organelles of the endomembrane system include: the nuclear membrane, the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, vesicles, endosomes, and plasma (cell) membrane among others. The system is defined more accurately as the set of membranes that forms a single functional and developmental unit, either being connected directly, or exchanging material through vesicle transport. Importantly, the endomembrane system does not include the membranes of plastids or mitochondria, but might have evolved partially from the actions of the latter.

Protein targeting or protein sorting is the biological mechanism by which proteins are transported to their appropriate destinations within or outside the cell. Proteins can be targeted to the inner space of an organelle, different intracellular membranes, the plasma membrane, or to the exterior of the cell via secretion. Information contained in the protein itself directs this delivery process. Correct sorting is crucial for the cell; errors or dysfunction in sorting have been linked to multiple diseases.

The lipid bilayer is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses are made of a lipid bilayer, as are the nuclear membrane surrounding the cell nucleus, and membranes of the membrane-bound organelles in the cell. The lipid bilayer is the barrier that keeps ions, proteins and other molecules where they are needed and prevents them from diffusing into areas where they should not be. Lipid bilayers are ideally suited to this role, even though they are only a few nanometers in width, because they are impermeable to most water-soluble (hydrophilic) molecules. Bilayers are particularly impermeable to ions, which allows cells to regulate salt concentrations and pH by transporting ions across their membranes using proteins called ion pumps.

Lipid-anchored proteins are proteins located on the surface of the cell membrane that are covalently attached to lipids embedded within the cell membrane. These proteins insert and assume a place in the bilayer structure of the membrane alongside the similar fatty acid tails. The lipid-anchored protein can be located on either side of the cell membrane. Thus, the lipid serves to anchor the protein to the cell membrane. They are a type of proteolipids.

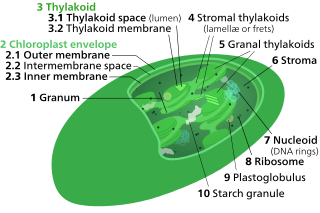

Thylakoids are membrane-bound compartments inside chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. They are the site of the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. Thylakoids consist of a thylakoid membrane surrounding a thylakoid lumen. Chloroplast thylakoids frequently form stacks of disks referred to as grana. Grana are connected by intergranal or stromal thylakoids, which join granum stacks together as a single functional compartment.

Semipermeable membrane is a type of biological or synthetic, polymeric membrane that allows certain molecules or ions to pass through it by osmosis. The rate of passage depends on the pressure, concentration, and temperature of the molecules or solutes on either side, as well as the permeability of the membrane to each solute. Depending on the membrane and the solute, permeability may depend on solute size, solubility, properties, or chemistry. How the membrane is constructed to be selective in its permeability will determine the rate and the permeability. Many natural and synthetic materials which are rather thick are also semipermeable. One example of this is the thin film on the inside of an egg.

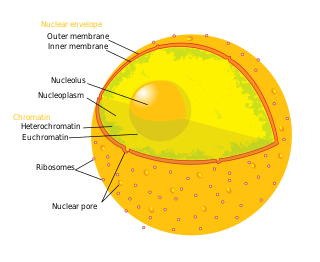

The nucleoplasm, also known as karyoplasm, is the type of protoplasm that makes up the cell nucleus, the most prominent organelle of the eukaryotic cell. It is enclosed by the nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane. The nucleoplasm resembles the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic cell in that it is a gel-like substance found within a membrane, although the nucleoplasm only fills out the space in the nucleus and has its own unique functions. The nucleoplasm suspends structures within the nucleus that are not membrane-bound and is responsible for maintaining the shape of the nucleus. The structures suspended in the nucleoplasm include chromosomes, various proteins, nuclear bodies, the nucleolus, nucleoporins, nucleotides, and nuclear speckles.

Endosomes are a collection of intracellular sorting organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are parts of endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi network. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membrane can follow this pathway all the way to lysosomes for degradation or can be recycled back to the cell membrane in the endocytic cycle. Molecules are also transported to endosomes from the trans Golgi network and either continue to lysosomes or recycle back to the Golgi apparatus.

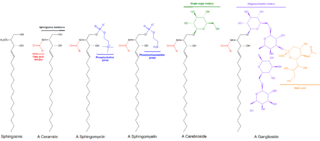

The plasma membranes of cells contain combinations of glycosphingolipids, cholesterol and protein receptors organised in glycolipoprotein lipid microdomains termed lipid rafts. Their existence in cellular membranes remains controversial. Indeed, Kervin and Overduin imply that lipid rafts are misconstrued protein islands, which they propose form through a proteolipid code. Nonetheless, it has been proposed that they are specialized membrane microdomains which compartmentalize cellular processes by serving as organising centers for the assembly of signaling molecules, allowing a closer interaction of protein receptors and their effectors to promote kinetically favorable interactions necessary for the signal transduction. Lipid rafts influence membrane fluidity and membrane protein trafficking, thereby regulating neurotransmission and receptor trafficking. Lipid rafts are more ordered and tightly packed than the surrounding bilayer, but float freely within the membrane bilayer. Although more common in the cell membrane, lipid rafts have also been reported in other parts of the cell, such as the Golgi apparatus and lysosomes.

Sphingomyelin is a type of sphingolipid found in animal cell membranes, especially in the membranous myelin sheath that surrounds some nerve cell axons. It usually consists of phosphocholine and ceramide, or a phosphoethanolamine head group; therefore, sphingomyelins can also be classified as sphingophospholipids. In humans, SPH represents ~85% of all sphingolipids, and typically make up 10–20 mol % of plasma membrane lipids.

Myristoylation is a lipidation modification where a myristoyl group, derived from myristic acid, is covalently attached by an amide bond to the alpha-amino group of an N-terminal glycine residue. Myristic acid is a 14-carbon saturated fatty acid (14:0) with the systematic name of n-tetradecanoic acid. This modification can be added either co-translationally or post-translationally. N-myristoyltransferase (NMT) catalyzes the myristic acid addition reaction in the cytoplasm of cells. This lipidation event is the most common type of fatty acylation and is present in many organisms, including animals, plants, fungi, protozoans and viruses. Myristoylation allows for weak protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions and plays an essential role in membrane targeting, protein–protein interactions and functions widely in a variety of signal transduction pathways.

In biology, cell signaling is the process by which a cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all cellular life in prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Lipid signaling, broadly defined, refers to any biological cell signaling event involving a lipid messenger that binds a protein target, such as a receptor, kinase or phosphatase, which in turn mediate the effects of these lipids on specific cellular responses. Lipid signaling is thought to be qualitatively different from other classical signaling paradigms because lipids can freely diffuse through membranes. One consequence of this is that lipid messengers cannot be stored in vesicles prior to release and so are often biosynthesized "on demand" at their intended site of action. As such, many lipid signaling molecules cannot circulate freely in solution but, rather, exist bound to special carrier proteins in serum.

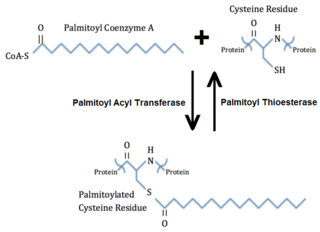

Palmitoylation is the covalent attachment of fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, to cysteine (S-palmitoylation) and less frequently to serine and threonine (O-palmitoylation) residues of proteins, which are typically membrane proteins. The precise function of palmitoylation depends on the particular protein being considered. Palmitoylation enhances the hydrophobicity of proteins and contributes to their membrane association. Palmitoylation also appears to play a significant role in subcellular trafficking of proteins between membrane compartments, as well as in modulating protein–protein interactions. In contrast to prenylation and myristoylation, palmitoylation is usually reversible (because the bond between palmitic acid and protein is often a thioester bond). The reverse reaction in mammalian cells is catalyzed by acyl-protein thioesterases (APTs) in the cytosol and palmitoyl protein thioesterases in lysosomes. Because palmitoylation is a dynamic, post-translational process, it is believed to be employed by the cell to alter the subcellular localization, protein–protein interactions, or binding capacities of a protein.

Microvesicles are a type of extracellular vesicle (EV) that are released from the cell membrane. In multicellular organisms, microvesicles and other EVs are found both in tissues and in many types of body fluids. Delimited by a phospholipid bilayer, microvesicles can be as small as the smallest EVs or as large as 1000 nm. They are considered to be larger, on average, than intracellularly-generated EVs known as exosomes. Microvesicles play a role in intercellular communication and can transport molecules such as mRNA, miRNA, and proteins between cells.

Membrane contact sites (MCS) are close appositions between two organelles. Ultrastructural studies typically reveal an intermembrane distance in the order of the size of a single protein, as small as 10 nm or wider, with no clear upper limit. These zones of apposition are highly conserved in evolution. These sites are thought to be important to facilitate signalling, and they promote the passage of small molecules, including ions, lipids and reactive oxygen species. MCS are important in the function of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), since this is the major site of lipid synthesis within cells. The ER makes close contact with many organelles, including mitochondria, Golgi, endosomes, lysosomes, peroxisomes, chloroplasts and the plasma membrane. Both mitochondria and sorting endosomes undergo major rearrangements leading to fission where they contact the ER. Sites of close apposition can also form between most of these organelles most pairwise combinations. First mentions of these contact sites can be found in papers published in the late 1950s mainly visualized using electron microscopy (EM) techniques. Copeland and Dalton described them as “highly specialized tubular form of endoplasmic reticulum in association with the mitochondria and apparently in turn, with the vascular border of the cell”.

The cell membrane is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment. The cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, made up of two layers of phospholipids with cholesterols interspersed between them, maintaining appropriate membrane fluidity at various temperatures. The membrane also contains membrane proteins, including integral proteins that span the membrane and serve as membrane transporters, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer (peripheral) side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes to facilitate interaction with the cell's environment. Glycolipids embedded in the outer lipid layer serve a similar purpose. The cell membrane controls the movement of substances in and out of a cell, being selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules. In addition, cell membranes are involved in a variety of cellular processes such as cell adhesion, ion conductivity, and cell signalling and serve as the attachment surface for several extracellular structures, including the cell wall and the carbohydrate layer called the glycocalyx, as well as the intracellular network of protein fibers called the cytoskeleton. In the field of synthetic biology, cell membranes can be artificially reassembled.

1-Lysophosphatidylcholines are a class of phospholipids that are intermediates in the metabolism of lipids. They result from the hydrolysis of an acyl group from the sn-1 position of phosphatidylcholine. They are also called 2-acyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholines. The synthesis of phosphatidylcholines with specific fatty acids occurs through the synthesis of 1-lysoPC. The formation of various other lipids generates 1-lysoPC as a by-product.

References

- 1 2 Forrester, M. T.; Hess, D. T.; Thompson, J. W.; Hultman, R.; Moseley, M. A.; Stamler, J. S.; Casey, P. J. (2010). "Site-specific analysis of protein S-acylation by resin-assisted capture". The Journal of Lipid Research. 52 (2): 393–398. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D011106 . PMC 3023561 . PMID 21044946.

- ↑ Hofemeister, H.; Weber, K.; Stick, R. (2000). "Association of Prenylated Proteins with the Plasma Membrane and the Inner Nuclear Membrane is Mediated by the Same Membrane-targeting Motifs" (PDF). Molecular Biology of the Cell. 11 (9): 3233–3246. doi:10.1091/mbc.11.9.3233. PMC 14988 . PMID 10982413.