Kenyanthropus is a genus of extinct hominin identified from the Lomekwi site by Lake Turkana, Kenya, dated to 3.3 to 3.2 million years ago during the Middle Pliocene. It contains one species, K. platyops, but may also include the 2 million year old Homo rudolfensis, or K. rudolfensis. Before its naming in 2001, Australopithecus afarensis was widely regarded as the only australopithecine to exist during the Middle Pliocene, but Kenyanthropus evinces a greater diversity than once acknowledged. Kenyanthropus is most recognisable by an unusually flat face and small teeth for such an early hominin, with values on the extremes or beyond the range of variation for australopithecines in regard to these features. Multiple australopithecine species may have coexisted by foraging for different food items, which may be reason why these apes anatomically differ in features related to chewing.

Paranthropus is a genus of extinct hominin which contains two widely accepted species: P. robustus and P. boisei. However, the validity of Paranthropus is contested, and it is sometimes considered to be synonymous with Australopithecus. They are also referred to as the robust australopithecines. They lived between approximately 2.9 and 1.2 million years ago (mya) from the end of the Pliocene to the Middle Pleistocene.

Homo ergaster is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Africa in the Early Pleistocene. Whether H. ergaster constitutes a species of its own or should be subsumed into H. erectus is an ongoing and unresolved dispute within palaeoanthropology. Proponents of synonymisation typically designate H. ergaster as "African Homo erectus" or "Homo erectus ergaster". The name Homo ergaster roughly translates to "working man", a reference to the more advanced tools used by the species in comparison to those of their ancestors. The fossil range of H. ergaster mainly covers the period of 1.7 to 1.4 million years ago, though a broader time range is possible. Though fossils are known from across East and Southern Africa, most H. ergaster fossils have been found along the shores of Lake Turkana in Kenya. There are later African fossils, some younger than 1 million years ago, that indicate long-term anatomical continuity, though it is unclear if they can be formally regarded as H. ergaster specimens. As a chronospecies, H. ergaster may have persisted to as late as 600,000 years ago, when new lineages of Homo arose in Africa.

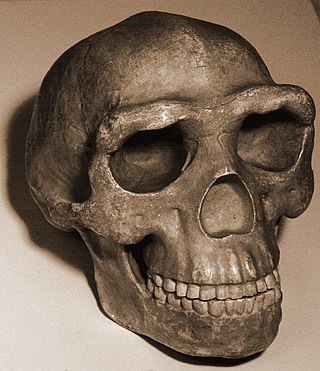

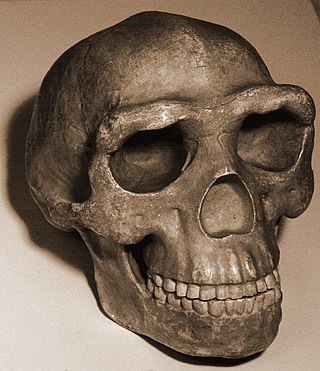

Homo rudolfensis is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2 million years ago (mya). Because H. rudolfensis coexisted with several other hominins, it is debated what specimens can be confidently assigned to this species beyond the lectotype skull KNM-ER 1470 and other partial skull aspects. No bodily remains are definitively assigned to H. rudolfensis. Consequently, both its generic classification and validity are debated without any wide consensus, with some recommending the species to actually belong to the genus Australopithecus as A. rudolfensis or Kenyanthropus as K. rudolfensis, or that it is synonymous with the contemporaneous and anatomically similar H. habilis.

In anatomy, the temporalis muscle, also known as the temporal muscle, is one of the muscles of mastication (chewing). It is a broad, fan-shaped convergent muscle on each side of the head that fills the temporal fossa, superior to the zygomatic arch so it covers much of the temporal bone. Temporal refers to the head's temples.

Meganthropus is an extinct genus of non-hominin hominid ape, known from the Pleistocene of Indonesia. It is known from a series of large jaw and skull fragments found at the Sangiran site near Surakarta in Central Java, Indonesia, alongside several isolated teeth. The genus has a long and convoluted taxonomic history. The original fossils were ascribed to a new species, Meganthropus palaeojavanicus, and for a long time was considered invalid, with the genus name being used as an informal name for the fossils.

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of paleontology and anthropology which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern humans, a process known as hominization, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinship lines within the family Hominidae, working from biological evidence and cultural evidence.

The MYH16 gene encodes a protein called myosin heavy chain 16, which is a muscle protein in mammals. At least in primates, it is a specialized muscle protein found only in the temporalis and masseter muscles of the jaw. Myosin heavy chain proteins are important in muscle contraction, and if they are missing, the muscles will be smaller. In non-human primates, MYH16 is functional and the animals have powerful jaw muscles. In humans, the MYH16 gene has a mutation that causes the protein not to function. Although the exact importance of this change in accounting for differences between humans and other apes is not yet clear, such a change may be related to increased brain size and finer control of the jaw, which facilitates speech. It is not clear how the MYH16 mutation relates to other changes to the jaw and skull in early human evolution.

In the human skull, a sagittal keel, or sagittal torus, is a thickening of part or all of the midline of the frontal bone, or parietal bones where they meet along the sagittal suture, or on both bones. Sagittal keels differ from sagittal crests, which are found in some earlier hominins and in a range of other mammals. While a proper crest functions in anchoring the muscles of mastication to the cranium, the keel is lower and rounded in cross-section, and the jaw muscles do not attach to it.

Australopithecus africanus is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived between about 3.3 and 2.1 million years ago in the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of South Africa. The species has been recovered from Taung, Sterkfontein, Makapansgat, and Gladysvale. The first specimen, the Taung child, was described by anatomist Raymond Dart in 1924, and was the first early hominin found. However, its closer relations to humans than to other apes would not become widely accepted until the middle of the century because most had believed humans evolved outside of Africa. It is unclear how A. africanus relates to other hominins, being variously placed as ancestral to Homo and Paranthropus, to just Paranthropus, or to just P. robustus. The specimen "Little Foot" is the most completely preserved early hominin, with 90% of the skeleton intact, and the oldest South African australopith. However, it is controversially suggested that it and similar specimens be split off into "A. prometheus".

Paranthropus aethiopicus is an extinct species of robust australopithecine from the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2.7–2.3 million years ago. However, it is much debated whether or not Paranthropus is an invalid grouping and is synonymous with Australopithecus, so the species is also often classified as Australopithecus aethiopicus. Whatever the case, it is considered to have been the ancestor of the much more robust P. boisei. It is debated if P. aethiopicus should be subsumed under P. boisei, and the terms P. boisei sensu lato and P. boisei sensu stricto can be used to respectively include and exclude P. aethiopicus from P. boisei.

Paranthropus robustus is a species of robust australopithecine from the Early and possibly Middle Pleistocene of the Cradle of Humankind, South Africa, about 2.27 to 0.87 million years ago. It has been identified in Kromdraai, Swartkrans, Sterkfontein, Gondolin, Cooper's, and Drimolen Caves. Discovered in 1938, it was among the first early hominins described, and became the type species for the genus Paranthropus. However, it has been argued by some that Paranthropus is an invalid grouping and synonymous with Australopithecus, so the species is also often classified as Australopithecus robustus.

Paranthropus boisei is a species of australopithecine from the Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2.5 to 1.15 million years ago. The holotype specimen, OH 5, was discovered by palaeoanthropologist Mary Leakey in 1959 at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania and described by her husband Louis a month later. It was originally placed into its own genus as "Zinjanthropus boisei", but is now relegated to Paranthropus along with other robust australopithecines. However, it is also argued that Paranthropus is an invalid grouping and synonymous with Australopithecus, so the species is also often classified as Australopithecus boisei.

The Hominini (hominins) form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae (hominines). They comprise two extant genera: Homo (humans) and Pan, and in standard usage exclude the genus Gorilla (gorillas), which is grouped separately within the subfamily Homininae.

The australopithecines, formally Australopithecina or Hominina, are generally any species in the related genera of Australopithecus and Paranthropus. It may also include members of Kenyanthropus, Ardipithecus, and Praeanthropus. The term comes from a former classification as members of a distinct subfamily, the Australopithecinae. They are classified within the Australopithecina subtribe of the Hominini tribe. These related species are sometimes collectively termed australopithecines, australopiths, or homininians. They are the extinct, close relatives of modern humans and, together with the extant genus Homo, comprise the human clade. Members of the human clade, i.e. the Hominini after the split from the chimpanzees, are called Hominina.

KNM-WT 17000 is a fossilized adult skull of the species Paranthropus aethiopicus. It was discovered in West Turkana, Kenya by Alan Walker in 1985. Estimated to be 2.5 million years old, the fossil is an adult with an estimated cranial capacity of 410 cc.

KNM ER 406 is an almost complete fossilized skull of the species Paranthropus boisei. It was discovered in Koobi Fora, Kenya by Richard Leakey and H. Mutua in 1969. This species is grouped with the Australopitecine genus, Paranthropus boisei because of the robusticity of the skull and the prominent characteristics. This species was found well preserved with a complete cranium but lacking dentition. He was known for his robust cranial features that showed the signs of adaptation of the ecological niches. The big chewing muscles attached to the sagittal crest are traits of this adaptation.

In physical anthropology, post-orbital constriction is the narrowing of the cranium (skull) just behind the eye sockets found in most non-human primates and early hominins. This constriction is very noticeable in non-human primates, slightly less so in Australopithecines, even less in Homo erectus and completely disappears in modern Homo sapiens. Post-orbital constriction index in non-human primates and hominin range in category from increased constriction, intermediate, reduced constriction and disappearance. The post-orbital constriction index is defined by either a ratio of minimum frontal breadth (MFB), behind the supraorbital torus, divided by the maximum upper facial breadth (BFM), bifrontomalare temporale, or as the maximum width behind the orbit of the skull.

Post-canine megadontia is a relative enlargement of the molars and premolars compared to the size of the incisors and canines. This phenomenon is seen in some early hominid ancestors such as Paranthropus aethiopicus.

Australopithecus sediba is an extinct species of australopithecine recovered from Malapa Cave, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa. It is known from a partial juvenile skeleton, the holotype MH1, and a partial adult female skeleton, the paratype MH2. They date to about 1.98 million years ago in the Early Pleistocene, and coexisted with Paranthropus robustus and Homo ergaster / Homo erectus. Malapa Cave may have been a natural death trap, the base of a long vertical shaft which creatures could accidentally fall into. A. sediba was initially described as being a potential human ancestor, and perhaps the progenitor of Homo, but this is contested and it could also represent a late-surviving population or sister species of A. africanus which had earlier inhabited the area.