A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or delegated authority issued commissions, also referred to as letters of marque, during wartime. The commission empowered the holder to carry on all forms of hostility permissible at sea by the usages of war. This included attacking foreign vessels and taking them as prizes and taking crews prisoner for exchange. Captured ships were subject to condemnation and sale under prize law, with the proceeds divided by percentage between the privateer's sponsors, shipowners, captains and crew. A percentage share usually went to the issuer of the commission.

Jean Lafitte was a French pirate, privateer, and slave trader who operated in the Gulf of Mexico in the early 19th century. He and his older brother Pierre spelled their last name Laffite, but English language documents of the time used "Lafitte". This has become the common spelling in the United States, including places named after him.

The era of piracy in the Caribbean began in the 1500s and phased out in the 1830s after the navies of the nations of Western Europe and North America with colonies in the Caribbean began hunting and prosecuting pirates. The period during which pirates were most successful was from the 1650s to the 1730s. Piracy flourished in the Caribbean because of the existence of pirate seaports such as Port Royal in Jamaica, Tortuga in Haiti, and Nassau in the Bahamas. Piracy in the Caribbean was part of a larger historical phenomenon of piracy, as it existed close to major trade and exploration routes in almost all the five oceans.

Pirate havens are ports or harbors that are a safe place for pirates to repair their vessels, resupply, recruit, spend their plunder, avoid capture, and/or lie in wait for merchant ships to pass by. The areas have governments that are unable or unwilling to enforce maritime laws. This creates favorable conditions for piracy. Pirate havens were places where pirates could find shelter, protection, support, and trade.

Hippolyte or Hipólito Bouchard, known in California as Pirata Buchar, was a French-born Argentine sailor and corsair (pirate) who fought for Argentina, Chile, and Peru.

Gustavia is the main town and capital of the island of Saint Barthélemy. Originally called Le Carénage, it was renamed in honor of King Gustav III of Sweden.

Henry Jennings was an English privateer-turned-pirate. Jennings's first recorded act of piracy took place in early 1716 when, with three vessels and 150–300 men, Jennings's fleet ambushed the Spanish salvage camp from the 1715 Treasure Fleet. After the Florida raid, Jennings and his crew also linked up with Benjamin Hornigold's "three sets of pirates" from New Providence Island.

Laurens Cornelis Boudewijn de Graaf was a Dutch pirate, mercenary, and naval officer in the service of the French colony of Saint-Domingue during the late 17th and early 18th century.

This timeline of the history of piracy in the 1640s is a chronological list of key events involving pirates between 1640 and 1649.

Vincenzo Gambi was a 19th-century Italian pirate. He was considered one of the most notorious men in the Gulf of Mexico during the early 19th century and raided shipping in the gulf for well over a decade before his death. Gambi was one of several pirates associated with Jean Lafitte and later assisted him during the Battle of New Orleans along with Dominique You, Rene Beluche and another fellow Italian-born pirate Louis "Nez Coupé" Chighizola. He is briefly mentioned in the 2007 historical novel Strangely Wonderful: Tale of Count Balashazy by Karen Mercury.

The Confederate privateers were privately owned ships that were authorized by the government of the Confederate States of America to attack the shipping of the United States. Although the appeal was to profit by capturing merchant vessels and seizing their cargoes, the government was most interested in diverting the efforts of the Union Navy away from the blockade of Southern ports, and perhaps to encourage European intervention in the conflict.

Mehdya, also Mehdia or Mehedya, is a town in Kénitra Province, Rabat-Salé-Kénitra, in north-western Morocco. Previously called al-Ma'mura, it was known as São João da Mamora under 16th century Portuguese occupation, or as La Mamora under 17th century Spanish occupation.

The West Indies Squadron, or the West Indies Station, was a United States Navy squadron that operated in the West Indies in the early nineteenth century. It was formed due to the need to suppress piracy in the Caribbean Sea, the Antilles and the Gulf of Mexico region of the Atlantic Ocean. This unit later engaged in the Second Seminole War until being combined with the Home Squadron in 1842. From 1822 to 1826 the squadron was based out of Saint Thomas Island until the Pensacola Naval Yard was constructed.

Aegean Sea anti-piracy operations began in 1825 when the United States government dispatched a squadron of ships to suppress Greek piracy in the Aegean Sea. The Greek civil wars of 1824–1825 and the decline of the Hellenic Navy made the Aegean quickly become a haven for pirates who sometimes doubled as privateers.

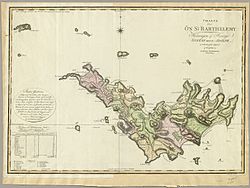

Saint Barthélemy, officially the Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Barthélemy, also known as St. Barts (English) or St. Barth (French), is an overseas collectivity of France in the Caribbean. The island lies about 30 kilometres (19 mi) southeast of the island of Saint Martin; it is northeast of the Dutch islands of Saba and Sint Eustatius, as well as north of the independent country of Saint Kitts and Nevis.

The West Indies Anti-Piracy Operations were a series of military operations and engagements undertaken by the United States Navy against pirates in and around the Antilles. Between 1814 and 1825, the American West Indies Squadron hunted pirates on both sea and land, primarily around Cuba and Puerto Rico. After the capture of Roberto Cofresi and his sloop Anne in 1825, acts of piracy became rare, and the operation was considered a success, although limited occurrences went on until slightly after the start of the 20th century.

The Atlantic World refers to the time period of the European colonization of the Americas, around 1492, to the early nineteenth century. Piracy became prevalent in this era because of the difficulty of policy in this vast area, the limited state control over many parts of the coast, and the competition between European powers. The best-known pirates of this era were the Golden Age Pirates who roamed the seas off North America, Africa, and the Caribbean coasts.

HMS Cambrian was a Royal Navy 40-gun fifth-rate frigate. She was built and launched at Bursledon in 1797 and served in the English Channel, off North America, and in the Mediterranean. She was briefly flagship of both Admiral Mark Milbanke and Vice-Admiral Sir Andrew Mitchell during her career, and was present at the Battle of Navarino. Cambrian was wrecked off the coast of Grabusa in 1828.

José Joaquim Almeida, was a Portuguese-born American privateer who fought in the Anglo-American War of 1812 and the Argentine War of Independence.

The Swedish colony of Saint Barthélemy existed for nearly a century. In 1784, one of French king Louis XVI's ministers ceded Saint Barthélemy to Sweden in exchange for trading rights in the Swedish port of Gothenburg. Swedish rule lasted until 1878 when the French repurchased the island.