Related Research Articles

The history of medicine is both a study of medicine throughout history as well as a multidisciplinary field of study that seeks to explore and understand medical practices, both past and present, throughout human societies.

Bartholomaeus Anglicus, also known as Bartholomew the Englishman and Berthelet, was an early 13th-century Scholastic of Paris, a member of the Franciscan order. He was the author of the compendium De proprietatibus rerum, dated c.1240, an early forerunner of the encyclopedia and a widely cited book in the Middle Ages. Bartholomew also held senior positions within the church and was appointed Bishop of Łuków in what is now Poland, although he was not consecrated to that position.

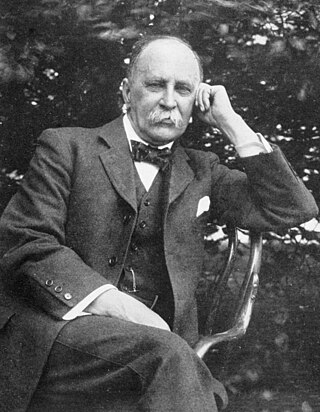

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first residency program for specialty training of physicians. He has frequently been described as the Father of Modern Medicine and one of the "greatest diagnosticians ever to wield a stethoscope". In addition to being a physician he was a bibliophile, historian, author, and renowned practical joker. He was passionate about medical libraries and medical history, having founded the History of Medicine Society, at the Royal Society of Medicine, London. He was also instrumental in founding the Medical Library Association of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Association of Medical Librarians along with three other people, including Margaret Charlton, the medical librarian of his alma mater, McGill University. He left his own large history of medicine library to McGill, where it became the Osler Library.

Trotula is a name referring to a group of three texts on women's medicine that were composed in the southern Italian port town of Salerno in the 12th century. The name derives from a historic female figure, Trota of Salerno, a physician and medical writer who was associated with one of the three texts. However, "Trotula" came to be understood as a real person in the Middle Ages and because the so-called Trotula texts circulated widely throughout medieval Europe, from Spain to Poland, and Sicily to Ireland, "Trotula" has historic importance in "her" own right.

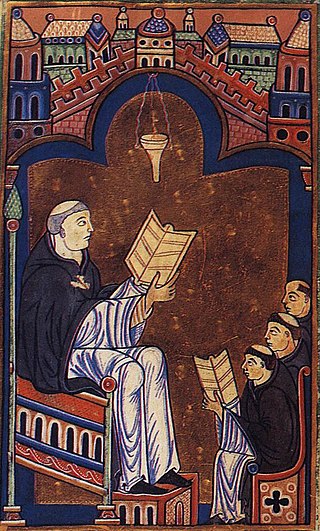

In the Middle Ages, the medicine of Western Europe was composed of a mixture of existing ideas from antiquity. In the Early Middle Ages, following the fall of the Western Roman Empire, standard medical knowledge was based chiefly upon surviving Greek and Roman texts, preserved in monasteries and elsewhere. Medieval medicine is widely misunderstood, thought of as a uniform attitude composed of placing hopes in the church and God to heal all sicknesses, while sickness itself exists as a product of destiny, sin, and astral influences as physical causes. But, especially in the second half of the medieval period, medieval medicine became a formal body of theoretical knowledge and was institutionalized in universities. Medieval medicine attributed illnesses, and disease, not to sinful behavior, but to natural causes, and sin was connected to illness only in a more general sense of the view that disease manifested in humanity as a result of its fallen state from God. Medieval medicine also recognized that illnesses spread from person to person, that certain lifestyles may cause ill health, and some people have a greater predisposition towards bad health than others.

The Schola Medica Salernitana was a medieval medical school, the first and most important of its kind. Situated on the Tyrrhenian Sea in the south Italian city of Salerno, it was founded in the 9th century and rose to prominence in the 10th century, becoming the most important source of medical knowledge in Western Europe at the time.

Hugh of Saint Victor was a Saxon canon regular and a leading theologian and writer on mystical theology.

In the history of medicine, "Islamic medicine", also known as "Arabian medicine" is the science of medicine developed in the Middle East, and usually written in Arabic, the lingua franca of Islamic civilization.

The Benveniste family is an old, noble, wealthy, and scholarly Sephardic Jewish family of Narbonne, France, and northern Spain established in the 11th century. The family was present in the 11th to the 15th centuries in Hachmei Provence, France, Barcelona, Aragon, and Castile.

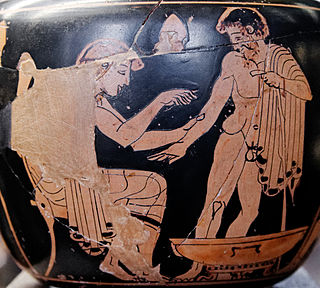

Ancient Greek medicine was a compilation of theories and practices that were constantly expanding through new ideologies and trials. The Greek term for medicine was iatrikē. Many components were considered in ancient Greek medicine, intertwining the spiritual with the physical. Specifically, the ancient Greeks believed health was affected by the humors, geographic location, social class, diet, trauma, beliefs, and mindset. Early on the ancient Greeks believed that illnesses were "divine punishments" and that healing was a "gift from the Gods". As trials continued wherein theories were tested against symptoms and results, the pure spiritual beliefs regarding "punishments" and "gifts" were replaced with a foundation based in the physical, i.e., cause and effect.

Sara Josephine Baker was an American physician notable for making contributions to public health, especially in the immigrant communities of New York City. Her fight against the damage that widespread urban poverty and ignorance caused to children, especially newborns, is perhaps her most lasting legacy. In 1917, she noted that babies born in the United States faced a higher mortality rate than soldiers fighting in World War I, drawing a great deal of attention to her cause. She also is known for (twice) tracking down Mary Mallon, better known as Typhoid Mary.

The presence of women in medicine, particularly in the practicing fields of surgery and as physicians, has been traced to the earliest of history. Women have historically had lower participation levels in medical fields compared to men with occupancy rates varying by race, socioeconomic status, and geography.

Medical missions in China by Catholic and Protestant physicians and surgeons of the 19th and early 20th centuries laid many foundations for modern medicine in China. Western medical missionaries established the first modern clinics and hospitals, provided the first training for nurses, and opened the first medical schools in China. Work was also done in opposition to the abuse of opium. Medical treatment and care came to many Chinese who were addicted, and eventually public and official opinion was influenced in favor of bringing an end to the destructive trade. By 1901, China was the most popular destination for medical missionaries. The 150 foreign physicians operated 128 hospitals and 245 dispensaries, treating 1.7 million patients. In 1894, male medical missionaries comprised 14 percent of all missionaries; women doctors were four percent. Modern medical education in China started in the early 20th century at hospitals run by international missionaries.

The history of hospitals began in antiquity with hospitals in Greece, the Roman Empire and on the Indian subcontinent as well, starting with precursors in the Asclepian temples in ancient Greece and then the military hospitals in ancient Rome. The Greek temples were dedicated to the sick and infirm but did not look anything like modern hospitals. The Romans did not have dedicated, public hospitals. Public hospitals, per se, did not exist until the Christian period. Towards the end of the 4th century, the "second medical revolution" took place with the founding of the first Christian hospital in the eastern Byzantine Empire by Basil of Caesarea, and within a few decades, such hospitals had become ubiquitous in Byzantine society. The hospital would undergo development and progress throughout Byzantine, medieval European and Islamic societies from the 5th to the 15th century. European exploration brought hospitals to colonies in North America, Africa, and Asia. St Bartholomew's hospital in West Smithfield in London, founded in 1123, is widely considered the oldest functioning hospital today. Originally a charitable institution, currently an NHS hospital it continues to provide free care to Londoners, as it has for 900 years. In contrast, the Mihintale Hospital in Sri Lanka, established in the 9th century is probably the site with the oldest archaeological evidence available for a hospital in the world. Serving monks and the local community, it represents early advancements in healthcare practices.

Jewish medicine is medical practice of the Jewish people, including writing in the languages of both Hebrew and Arabic. 28% of Nobel Prize winners in medicine have been Jewish, although Jews comprise less than 0.2% of the world's population.

Midwifery in the Middle Ages impacted women's work and health prior to the professionalization of medicine. During the Middle Ages in Western Europe, people relied on the medical knowledge of Roman and Greek philosophers, specifically Galen, Hippocrates, and Aristotle. These medical philosophers focused primarily on the health of men, and women's health issues were understudied. Thus, these philosophers did not focus on the baby and they encouraged women to handle women's issues. In fact, William L. Minkowski asserted that a male's reputation was negatively affected if he associated with or treated pregnant patients. Resultantly, male physicians did not engage with pregnant patients, and women had a place in medicine as midwives. Myriam Greilsammer notes that an additional opposition to men's involvement in childbearing was that men should not associate with female genitalia throughout the secret practices of childbearing. The prevalence of this mindset allowed women to continue the practice of midwifery throughout most of the Medieval era with little or no male influence on their affairs. Minkowski writes that in Guy de Chauliac's fourteenth-century work Chirurgia magna, "he wrote that he was unwilling to discourse on midwifery because the field was dominated by women." However, changing views of medicine caused the women's role as midwife to be pushed aside as the professionalization of medical practitioners began to go up.

This is a timeline of women in science, spanning from ancient history up to the 21st century. While the timeline primarily focuses on women involved with natural sciences such as astronomy, biology, chemistry and physics, it also includes women from the social sciences and the formal sciences, as well as notable science educators and medical scientists. The chronological events listed in the timeline relate to both scientific achievements and gender equality within the sciences.

Virdimura was a Sicilian Jewish doctor, the first woman officially certified to practice medicine in Sicily.

John of St. Giles was an English Dominican friar and physician.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tallan, Emily Taitz, Sondra Henry, Cheryl (2003). The JPS guide to Jewish women : 600 B.C.E.-1900 C.E. (1st ed.). Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. p. 86. ISBN 0827607520.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ York, Laura (2002). "Sarah of St. Gilles (fl. 1326)". In Commire, Anne (ed.). Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Waterford, Connecticut: Yorkin Publications. p. 800. ISBN 0-7876-4074-3.

- ↑ Advocate: America's Jewish Journal. 655. 29 January 1921.

- ↑ Shatzmiller, Joseph (1994). Jews, medicine, and Medieval society. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. p. 24. ISBN 0520080599.