Etruscan was the language of the Etruscan civilization in the ancient region of Etruria, in Etruria Padana and Etruria Campana in what is now Italy. Etruscan influenced Latin but was eventually completely superseded by it. The Etruscans left around 13,000 inscriptions that have been found so far, only a small minority of which are of significant length; some bilingual inscriptions with texts also in Latin, Greek, or Phoenician; and a few dozen purported loanwords. Attested from 700 BC to AD 50, the relation of Etruscan to other languages has been a source of long-running speculation and study, with it mostly being referred to as one of the Tyrsenian languages, at times as an isolate, and a number of other less well-known hypotheses.

The Etruscan civilization was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in ancient Italy, with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roughly what is now Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Lazio, as well as what are now the Po Valley, Emilia-Romagna, south-eastern Lombardy, southern Veneto, and western Campania.

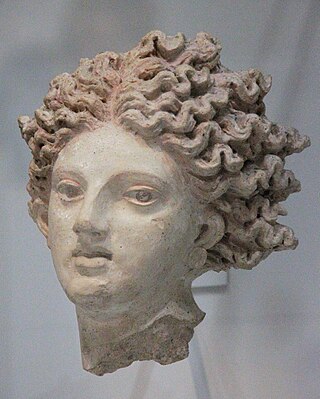

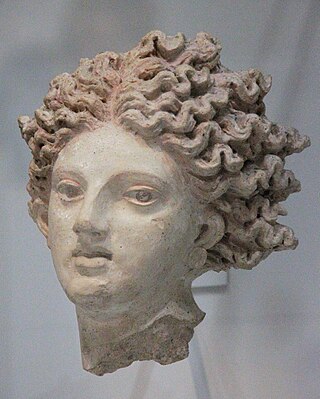

Etruscan religion comprises a set of stories, beliefs, and religious practices of the Etruscan civilization, heavily influenced by the mythology of ancient Greece, and sharing similarities with concurrent Roman mythology and religion. As the Etruscan civilization was gradually assimilated into the Roman Republic from the 4th century BC, the Etruscan religion and mythology were partially incorporated into ancient Roman culture, following the Roman tendency to absorb some of the local gods and customs of conquered lands. The first attestations of an Etruscan religion can be traced back to the Villanovan culture.

Aita, also spelled Eita, is an epithet of the Etruscan chthonic fire god Śuri as god of the underworld, roughly equivalent to the Greek god Hades.

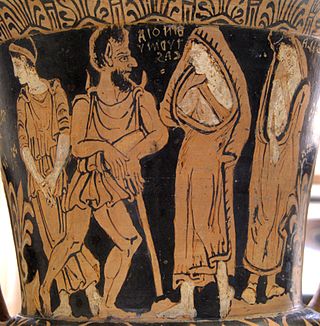

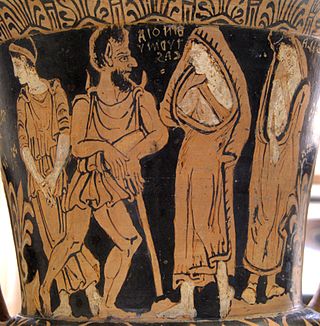

In Etruscan mythology, Charun acted as one of the psychopompoi of the underworld. He is often portrayed with Vanth, a winged figure also associated with the underworld.

In Etruscan religion, Fufluns or Puphluns was a god of plant life, happiness, wine, health, and growth in all things. He is mentioned twice among the gods listed in the inscriptions of the Liver of Piacenza, being listed among the 16 gods that rule the Etruscan astrological houses. He is the 9th of those 16 gods. He is the son of Semla and the god Tinia. He was worshipped at Populonia and is the namesake of that town.

Tages was claimed as a founding prophet of Etruscan religion who is known from reports by Latin authors of the late Roman Republic and Roman Empire. He revealed a cosmic view of divinity and correct methods of ascertaining divine will concerning events of public interest. Such divination was undertaken in Roman society by priestly officials called haruspices.

Massimo Pallottino was an Italian archaeologist specializing in Etruscan civilization and art.

The Tabula Cortonensis is a 2200-year-old, inscribed bronze tablet in the Etruscan language, discovered in Cortona, Italy. It may record for posterity the details of an ancient legal transaction which took place in the ancient Tuscan city of Cortona, known to the Etruscans as Curtun. Its 40-line, 200-word, two-sided inscription is the third longest inscription found in the Etruscan language, after the Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis and the Tabula Capuana, and the longest discovered in the 20th century.

The Cippus Perusinus is a stone tablet (cippus) discovered on the hill of San Marco, in Perugia, Italy, in 1822. The tablet bears 46 lines of incised Etruscan text, about 130 words. The cippus, which seems to have been a border stone, appears to display a text dedicating a legal contract between the Etruscan families of Velthina and Afuna, regarding the sharing or use, including water rights, of a property upon which there was a tomb belonging to the noble Velthinas.

Etruscology is the study of the ancient civilization of the Etruscans in Italy, which was incorporated into an expanding Roman Empire during the period of Rome's Middle Republic. Since the Etruscans were politically and culturally influential in pre-Republican Rome, many Etruscologists are also scholars of the history, archaeology, and culture of Rome.

The Tomb of Orcus, sometimes called the Tomb of Murina, is a 4th-century BC Etruscan hypogeum in Tarquinia, Italy. Discovered in 1868, it displays Hellenistic influences in its remarkable murals, which include the portrait of Velia Velcha, an Etruscan noblewoman, and the only known pictorial representation of the daemon Tuchulcha. In general, the murals are noted for their depiction of death, evil, and unhappiness.

In classical antiquity, several theses were elaborated on the origin of the Etruscans from the 5th century BC, when the Etruscan civilization had been already established for several centuries in its territories, that can be summarized into three main hypotheses. The first is the autochthonous development in situ out of the Villanovan culture, as claimed by the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus who described the Etruscans as indigenous people who had always lived in Etruria. The second is a migration from the Aegean Sea, as claimed by two Greek historians: Herodotus, who described them as a group of immigrants from Lydia in Anatolia, and Hellanicus of Lesbos who claimed that the Tyrrhenians were the Pelasgians originally from Thessaly, Greece, who entered Italy at the head of the Adriatic Sea in Northern Italy. The third hypothesis was reported by Livy and Pliny the Elder, and puts the Etruscans in the context of the Rhaetian people to the north and other populations living in the Alps.

Catha is a female Etruscan lunar or solar deity, who may also be connected to childbirth, and has a connection to the underworld. Catha is also the goddess of the south sanctuary at Pyrgi, Italy.

Culsans (Culśanś) is an Etruscan deity, known from four inscriptions and a variety of iconographical material which includes coins, statuettes, and a sarcophagus. Culśanś is usually rendered as a male deity with two faces and at least two statuettes depicting him have been found in close association with city gates. These characteristics suggest that he was a protector of gateways, who could watch over the gate with two pairs of eyes.

Maria Bonghi Jovino is an Italian archaeologist. Bonghi Jovino was Professor of Etruscology and Italic Archaeology at the University of Milan.

The Lead Plaque of Magliano, which contains 73 words in the Etruscan language, seems to be a dedicatory text, including as it does many names of mostly underworld deities. It was found in 1882, and dates to the mid 5th century BC. It is now housed in the National Archaeological Museum in Florence.

Śuri, Latinized as Soranus, was an ancient Etruscan infernal, volcanic and solar fire god, also venerated by other Italic peoples – among them Capenates, Faliscans, Latins and Sabines – and later adopted into ancient Roman religion.

Manth, latinized as Mantus, is an epithet of the Etruscan chthonic fire god Śuri as god of the underworld; this name was primarily used in the Po Valley, as described by Servius, but a dedication to the god manθ from the Archaic period was found in a sanctuary in Pontecagnano, Southern Italy. His name is thought to be the origin of Mantua, the birthplace of Virgil.