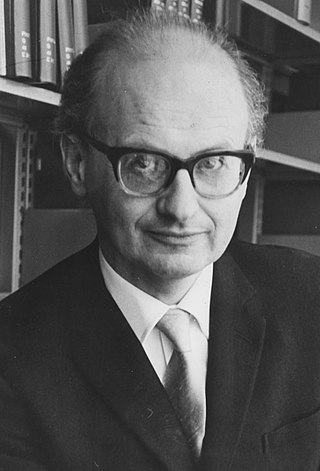

Falsifiability is a deductive standard of evaluation of scientific theories and hypotheses, introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper in his book The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934). A theory or hypothesis is falsifiable if it can be logically contradicted by an empirical test.

Sir Karl Raimund Popper was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the classical inductivist views on the scientific method in favour of empirical falsification. According to Popper, a theory in the empirical sciences can never be proven, but it can be falsified, meaning that it can be scrutinised with decisive experiments. Popper was opposed to the classical justificationist account of knowledge, which he replaced with critical rationalism, namely "the first non-justificational philosophy of criticism in the history of philosophy".

Postmodern philosophy is a philosophical movement that arose in the second half of the 20th century as a critical response to assumptions allegedly present in modernist philosophical ideas regarding culture, identity, history, or language that were developed during the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment. Postmodernist thinkers developed concepts like difference, repetition, trace, and hyperreality to subvert "grand narratives", univocity of being, and epistemic certainty. Postmodern philosophy questions the importance of power relationships, personalization, and discourse in the "construction" of truth and world views. Many postmodernists appear to deny that an objective reality exists, and appear to deny that there are objective moral values.

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultimate purpose of science. This discipline overlaps with metaphysics, ontology, and epistemology, for example, when it explores the relationship between science and truth. Philosophy of science focuses on metaphysical, epistemic and semantic aspects of science. Ethical issues such as bioethics and scientific misconduct are often considered ethics or science studies rather than the philosophy of science.

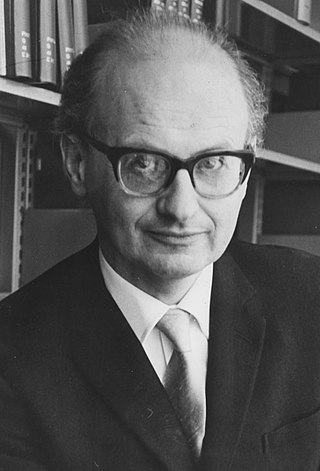

Imre Lakatos was a Hungarian philosopher of mathematics and science, known for his thesis of the fallibility of mathematics and its "methodology of proofs and refutations" in its pre-axiomatic stages of development, and also for introducing the concept of the "research programme" in his methodology of scientific research programmes.

Relativism is a family of philosophical views which deny claims to objectivity within a particular domain and assert that valuations in that domain are relative to the perspective of an observer or the context in which they are assessed. There are many different forms of relativism, with a great deal of variation in scope and differing degrees of controversy among them. Moral relativism encompasses the differences in moral judgments among people and cultures. Epistemic relativism holds that there are no absolute principles regarding normative belief, justification, or rationality, and that there are only relative ones. Alethic relativism is the doctrine that there are no absolute truths, i.e., that truth is always relative to some particular frame of reference, such as a language or a culture. Some forms of relativism also bear a resemblance to philosophical skepticism. Descriptive relativism seeks to describe the differences among cultures and people without evaluation, while normative relativism evaluates the word truthfulness of views within a given framework.

Cultural relativism is the idea that a person's beliefs and practices should be understood based on that person's own culture. Proponents of cultural relativism also tend to argue that the norms and values of one culture should not be evaluated using the norms and values of another.

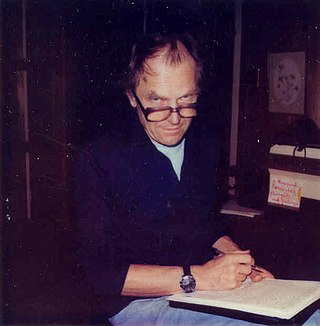

Paul Karl Feyerabend was an Austrian philosopher best known for his work in the philosophy of science. He started his academic career as lecturer in the philosophy of science at the University of Bristol (1955–1958); afterwards, he moved to the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught for three decades (1958–1989). At various points in his life, he held joint appointments at the University College London (1967–1970), the London School of Economics (1967), the FU Berlin (1968), Yale University (1969), the University of Auckland, the University of Sussex (1974), and, finally, the ETH Zurich (1980–1990). He gave lectures and lecture series at the University of Minnesota (1958-1962), Stanford University (1967), the University of Kassel (1977) and the University of Trento (1992).

Scientism is the opinion that science and the scientific method are the best or only way to render truth about the world and reality.

Reflective equilibrium is a state of balance or coherence among a set of beliefs arrived at by a process of deliberative mutual adjustment among general principles and particular judgements. Although he did not use the term, philosopher Nelson Goodman introduced the method of reflective equilibrium as an approach to justifying the principles of inductive logic. The term reflective equilibrium was coined by John Rawls and popularized in his A Theory of Justice as a method for arriving at the content of the principles of justice.

Ian MacDougall Hacking was a Canadian philosopher specializing in the philosophy of science. Throughout his career, he won numerous awards, such as the Killam Prize for the Humanities and the Balzan Prize, and was a member of many prestigious groups, including the Order of Canada, the Royal Society of Canada and the British Academy.

Robert Paul Wolff is an American political philosopher and professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

In philosophy of science and epistemology, the demarcation problem is the question of how to distinguish between science and non-science. It also examines the boundaries between science, pseudoscience and other products of human activity, like art and literature and beliefs. The debate continues after more than two millennia of dialogue among philosophers of science and scientists in various fields. The debate has consequences for what can be termed "scientific" in topics such as education and public policy.

Commensurability is a concept in the philosophy of science whereby scientific theories are said to be "commensurable" if scientists can discuss the theories using a shared nomenclature that allows direct comparison of them to determine which one is more valid or useful. On the other hand, theories are incommensurable if they are embedded in starkly contrasting conceptual frameworks whose languages do not overlap sufficiently to permit scientists to directly compare the theories or to cite empirical evidence favoring one theory over the other. Discussed by Ludwik Fleck in the 1930s, and popularized by Thomas Kuhn in the 1960s, the problem of incommensurability results in scientists talking past each other, as it were, while comparison of theories is muddled by confusions about terms, contexts and consequences.

The sociology of scientific knowledge (SSK) is the study of science as a social activity, especially dealing with "the social conditions and effects of science, and with the social structures and processes of scientific activity." The sociology of scientific ignorance (SSI) is complementary to the sociology of scientific knowledge. For comparison, the sociology of knowledge studies the impact of human knowledge and the prevailing ideas on societies and relations between knowledge and the social context within which it arises.

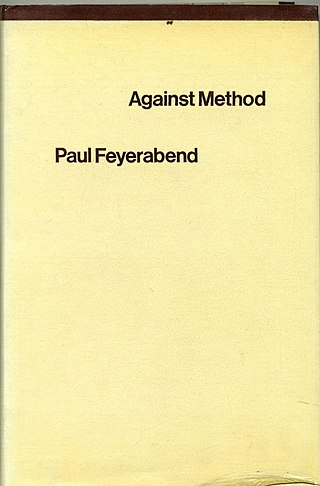

Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge is a 1975 book by Austrian-born philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend. The central thesis of the book is that science should become an anarchic enterprise. In the context of the work, the term "anarchy" refers to epistemological anarchy, which does not remain within one single prescriptive scientific method on the grounds that any such method would restrict scientific progress. The work is notable in the history and philosophy of science partially due to its detailed case study of Galileo's hypothesis that the earth rotates on its axis and has since become a staple reading in introduction to philosophy of science courses at undergraduate and graduate levels.

Factual relativism argues that truth itself is relative. This form of relativism has its own particular problem, regardless of whether one is talking about truth being relative to the individual, the position or purpose of the individual, or the conceptual scheme within which the truth was revealed. This problem centers on what Maurice Mandelbaum in 1962 termed the "self-excepting fallacy." Largely because of the self-excepting fallacy, few authors in the philosophy of science currently accept alethic cognitive relativism. Factual relativism is a way to reason where facts used to justify any claims are understood to be relative and subjective to the perspective of those proving or falsifying the proposition.

The Structure of Science: Problems in the Logic of Scientific Explanation is a 1961 book about the philosophy of science by the philosopher Ernest Nagel, in which the author discusses the nature of scientific inquiry with reference to both natural science and social science. Nagel explores the role of reduction in scientific theories and the relationship of wholes to their parts, and also evaluates the views of philosophers such as Isaiah Berlin.

Farewell to Reason is a 1987 book by the Austrian philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend. The book includes some reprinted essays published in other venues and was published by Verso Books, which also published Against Method and Science in a Free Society. The primary goal of the book is to trace the historical origins of "rationalism" and argue for a version of relativism and cultural diversity.

Conquest of Abundance: A Tale of Abstract versus the Richness of Being is the last book by the Austrian philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend, published posthumously by the University of Chicago Press in 1999. It is edited by Bert Terpstra and includes a foreword from Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend, Feyerabend’s 4th and final wife. The book was uncompleted due to Feyerabend’s death in 1994 and was written to fulfill a promise made to Borrini-Feyerabend. The unfinished manuscript was published alongside several other previously published papers that engaged with the core themes of the book.