Scuffletown was a community in Robeson County, North Carolina, United States in the 1700s and 1800s dominated by Lumbee Native Americans.

Scuffletown was a community in Robeson County, North Carolina, United States in the 1700s and 1800s dominated by Lumbee Native Americans.

The Lumbee people in southeastern North Carolina originated from various Native American/Indian groups which were greatly impacted by conflicts and infectious diseases dating back to the period of European colonization. Those who survived these disruptions grouped together as homogenous communities. In 1830, the United States government began a policy of Indian removal, forcibly relocating Native American populations in the American South further west. Native Americans in Robeson County, North Carolina, were not subject to removal. [1] Culturally, this group was not particularly distinct from proximate European Americans; they were mostly agrarian, and shared similar styles of dress, homes, and music. They also spoke English and were mostly Protestants. Their identity was rooted in kinship and shared location. [2] Through intermarriage, they acquired some white and black ancestry. [3] Not viewed as Native Americans by the state of North Carolina until the 1880s, these people were generally dubbed "mulattos" by locals and in federal documents throughout the mid-1800s to distinguish them from blacks. [4] They were recognized under the name "Lumbee" in the 1950s. [5]

The date of Scuffletown's formation is unknown. [6] According to Mary Norment, a white Robesonian and the widow of a man killed in the Lowry War, and North Carolina Adjutant General John Gorman, Scuffletown was created after Tuscarora farmers were forced off their land in the 1700s and retreated into sandy, swampy lands in the vicinity of the Lumber River, where they were joined by runaway enslaved Africans. [7] Conversely, one white Robesonian reported to a newspaper in the 1870s that most Scuffletonians were of a mix of white and indigenous descent, very rarely intermingling with blacks. [8] According to historian Malinda Maynor Lowery, in the early 1800s intermarriage and social interaction among blacks, whites, and Native Americans was common in the community, though this faded over subsequent decades. [9]

"Scuffletown" was a pejorative name applied to the community by white Robesonians. It was also known as "the Settlement". [10] The origins of the name are not certain. [11] Norment suggested that one possible origin of the name was "It was generally a scuffle with the mulattos to live to live—to keep body and soul together, owing to their improvident habits." [12] Another explanation she offered was that mulattos were known to gather at a tavern at Harper's Ferry in the area owned by James Lowry (an ancestor of Lumbee outlaw Henry Berry Lowry) in the 1700s and, after becoming drunk, would do a "broad shuffle". [12] One tradition suggests that Continental Army General Burwell Vick was staying at the tavern in the 1700s after the American Revolution and named the surrounding area in homage to drunken scuffles that took place at the tavern, as a way of suggesting the lawlessness of the community. [13] Other historians have suggested that the name was a corruption of "Scovilletown", a possible allusion to the Scoville family. [11] Local residents were known as "Scuffletonians". [14]

The actual location of Scuffletown is disputed. Some scholars believe it was in the vicinity of the later town of Pembroke while others place it at Moss Neck. Historians Adolph L. Dial and David K. Eliades believed that it was a mobile community. Others still believe the name applied broadly to any concentration of Native Americans in Robeson County. [15] According to the historian Lowery, Scuffeltown encompassed many smaller locations including Prospect, Hopewell, New Hope, Union Chapel, Saddletree, Harper's Ferry, Saint Annah, Fair Grove, and Moss Neck. [13] Journalist Connee Brayboy included Moss Neck, Pates, Red Banks, Evans Crossing, and Brooks' Settlement within the area of Scuffletown. She wrote "the boundaries of 'Scuffletown' cannot be defined because it was not the custom of native people to define geographic boundaries...[the Scuffletown] designation is more an identification of families and clans, while the incorporated limits of Pembroke are recognized as the geographic, economic, and educational center of Native American country." [16]

Scuffletown had no public streets or buildings and no local government. Contemporary accounts by Norment and journalists describe it as a swampy area marked by occasional hills and log cabins of rudimentary build. [17] These one-room structures had minimal furnishings, and their occupants usually slept on dirt floors. [18] Most had no windows, though some had peepholes near their doors. [19] Most of these provided shelter to individual nuclear families. [20] These homesteads were typically surrounded by three or four acres of fields, which were plowed and planted with corn, potatoes, and rice. The poor quality of the land generated minimal agricultural yields. [17] Horses were rare, and oxen were used as draft animals. [18] Dogs were kept for hunting. Water was sourced from hand-dug wells. [19] Scuffletown residents, who were mostly poor, also provided for themselves by picking wild blackberries and whortleberries, hunting and fishing, or working as day laborers for neighboring farmers. The latter work included digging ditches, splitting shingles, harvesting sap for turpentine, and other various jobs. [17] Norment reported the Lowry and Oxendine families to have better means than other Scuffletonians, with the former having better homes owing to many family members being carpenters by trade. [19] [lower-alpha 1]

According to Norment, the Scuffletonians were notorious for loose morals and committing petty crime, including theft of neighbors' livestock and engaging in drunken brawls. She also reported that despite being Protestant Christians, many were superstitious and believed in fairies, ghosts, and spirits. [22] They attended their own churches and would sometimes listen to preaching circuit ministers. [23] [24] H. W. Guion, a former director of the Wilmington, Charlotte and Rutherford Railroad, testified that they were peaceful but were stubborn and lazy workers. [25] Many Scuffletonians suffered from prolonged periods of hunger, especially during the American Civil War, when Scuffletonians attempting to dodge labor conscription for Confederate fort construction hid in the swamps and did not tend to their crops. [26] [27] The tension raised by the labor conscription and the subsequent murder in early 1865 of James Brantley Harris, a white Confederate Home Guardsman who had lived in Scuffletown and enforced the conscription, helped spark the Lowry War, a conflict between a mostly-Lumbee group of outlaws and the local white authorities. [28] [29]

Christian mythology is the body of myths associated with Christianity. The term encompasses a broad variety of legends and narratives, especially those considered sacred narratives. Mythological themes and elements occur throughout Christian literature, including recurring myths such as ascending to a mountain, the axis mundi, myths of combat, descent into the Underworld, accounts of a dying-and-rising god, a flood myth, stories about the founding of a tribe or city, and myths about great heroes of the past, paradises, and self-sacrifice.

Religion and mythology differ in scope but have overlapping aspects. Both terms refer to systems of concepts that are of high importance to a certain community, making statements concerning the supernatural or sacred. Generally, mythology is considered one component or aspect of religion. Religion is the broader term: besides mythological aspects, it includes aspects of ritual, morality, theology, and mystical experience. A given mythology is almost always associated with a certain religion such as Greek mythology with Ancient Greek religion. Disconnected from its religious system, a myth may lose its immediate relevance to the community and evolve—away from sacred importance—into a legend or folktale.

Robeson County is a county in the southern part of the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 116,530. Its county seat is Lumberton. The county was formed in 1787 from part of Bladen County. It was named in honor of Col. Thomas Robeson of Tar Heel, a hero of the Revolutionary War.

Pembroke is a town in Robeson County, North Carolina, United States. It is about 90 miles inland and northwest from the Atlantic Coast. The population was 2,973, at the 2010 census. The town is the seat of the state-recognized Lumbee tribe of North Carolina, as well as the home of The University of North Carolina at Pembroke.

Prospect is a census-designated place (CDP) in Robeson County, North Carolina, United States. The population was 690 at the 2000 census. Located due northeast of Pembroke, Prospect is a traditionally Methodist community, with its church members largely becoming representatives for the entirety of the American Indian-Methodist community. Prospect is noted for one of its native sons, Adolph Dial, whose contributions to American Indian Studies have led to an heightened awareness of the local Lumbee Tribe and Native Americans throughout the Southeastern United States.

Mircea Eliade was a Romanian historian of religion, fiction writer, philosopher, and professor at the University of Chicago. He was a leading interpreter of religious experience, who established paradigms in religious studies that persist to this day. His theory that hierophanies form the basis of religion, splitting the human experience of reality into sacred and profane space and time, has proved influential. One of his most instrumental contributions to religious studies was his theory of eternal return, which holds that myths and rituals do not simply commemorate hierophanies, but, at least to the minds of the religious, actually participate in them.

Adolph Schayes was an American professional basketball player and coach in the National Basketball Association (NBA). A top scorer and rebounder, he was a 12-time NBA All-Star and a 12-time All-NBA selection. Schayes won an NBA championship with the Syracuse Nationals in 1955. He was named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History and one of the 76 players named to the NBA 75th Anniversary Team in 2021. He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1973.

The Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina is a state-recognized tribe in North Carolina numbering approximately 55,000 enrolled members, most of them living primarily in Robeson, Hoke, Cumberland and Scotland counties. The Lumbee Tribe is the largest state tribe in North Carolina, the largest state tribe east of the Mississippi River, and the ninth largest non-federally recognized tribe in the United States. The Lumbee take their name from the Lumbee River, which winds through Robeson County. Pembroke, North Carolina, is the economic, cultural and political center of the tribe.

Comparative mythology is the comparison of myths from different cultures in an attempt to identify shared themes and characteristics. Comparative mythology has served a variety of academic purposes. For example, scholars have used the relationships between different myths to trace the development of religions and cultures, to propose common origins for myths from different cultures, and to support various psychological theories.

Henry Berry Lowry was an American outlaw. A Lumbee Native American, he led the Lowry Gang in North Carolina during and after the American Civil War. Many local North Carolinians remember him as a Robin Hood figure. Lowry was described by George Alfred Townsend, a correspondent for the New York Herald in the late 19th century, as "[o]ne of those remarkable executive spirits that arises now and then in a raw community without advantages other than those given by nature."

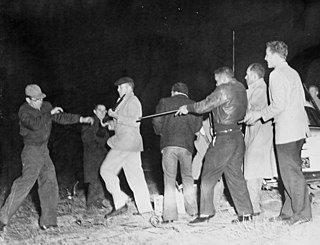

The Battle of Hayes Pond, also known as the Battle of Maxton Field or the Maxton Riot, was an armed confrontation between members of a Ku Klux Klan (KKK) organization and Lumbee Indians at a Klan rally near Maxton, North Carolina, on the night of January 18, 1958. The clash resulted in the disruption of the rally and a significant amount of media coverage praising the Lumbees and condemning the Klansmen.

The Călușari are the members of a fraternal secret society who practice a ritual acrobatic dance known as the căluș. Originally Romanian, the practice later spread to Bulgaria and North Macedonia. From three weeks after Easter until Pentecost, called Rusalii in Romanian, for around two weeks they have traditionally travelled to all their local communities where they would dance, accompanied by a few fiddlers.

The Lowry War or Lowrie War was a conflict that took place in and around Robeson County, North Carolina, United States from 1864 to 1874 between a group of mostly Native American outlaws and civil local, state, and federal authorities. The conflict is named for Henry Berry Lowry, a Lumbee who led a gang of American Indian, white and black men which robbed area farms and killed public officials who pursued them.

The history of Native Americans in Baltimore and what is now Baltimore dates back at least 12,000 years. As of 2014, Baltimore is home to a small Native American population, centered in East Baltimore. The majority of Native Americans now living in Baltimore belong to the Lumbee, Piscataway, and Cherokee nations. The Piscataway people are indigenous to Southern Maryland, living in the area for centuries prior to European colonization, and are recognized as a tribe by the state of Maryland. The Lumbee and Cherokee are indigenous to North Carolina and neighboring states of the Southeastern United States. Many of the Lumbee and Cherokee migrated to Baltimore during the mid-20th century along with other migrants from the Southern United States, such as African-Americans and white Appalachians.

Adolph Lorenz Dial was an American historian, professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, and a specialist in the field of American Indian Studies. Dial was a member of the Lumbee Tribe and a graduate of Pembroke State College, where he obtained a bachelor's degree in social studies. Soon after graduating, Dial enlisted with the United States Army, completing a tour of duty in the European theater of World War II. Post-military, Dial obtained his master's degree and an advanced certificate in social studies from Boston University. Hired by Pembroke State College in 1958, Dial would go on to create the college's American Indian Studies program, the first of its kind at any university in the Southeast. In addition to his role in academia, Dial was a member of the North Carolina House of Representatives for a single term. Over the course of his career, Dial devoted the majority of his academic work towards enriching and publicizing the history of the Lumbee Tribe and its importance within the history of North Carolina, and within the greater narrative of Native American peoples. Dial died on December 24, 1995, 12 days after his 73rd birthday.

Rhoda Strong Lowry, also known as the "Queen of Scuffletown", was a Lumbee Native American woman from North Carolina. She allegedly helped her husband, Henry Berry Lowrie, flee after he and his gang killed many white people in attempt to avenge his father and brother's deaths.

Ruth Dial Woods is an American educator and activist. A member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, she was the first woman to serve as the associate superintendent of the Robeson County Public Schools and to receive an at-large appointment to the University of North Carolina Board of Governors. After teaching in the public school system of Robeson County for 27 years, she joined the faculty at Fayetteville State University. In addition to her work as an educator, Woods was involved in the Civil Rights Movement, the Women's liberation movement, and the American Indian Movement. She has served as a community development consultant for the United States Department of Labor and as a consultant for the Lumbee Tribal Council for administration of tribal programs. The recipient of numerous awards and honors for her work in human rights and education, in 2011, she was inducted into the North Carolina Women's Hall of Fame.

Moss Neck is a community in Robeson County, North Carolina, United States.

Pates is a community in Robeson County, North Carolina, United States.

Francis "Frank" Marion Wishart was an American military officer. He served with the 46th North Carolina Infantry Regiment of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Wounded in combat, he left the war with rank of captain before returning to Robeson County, North Carolina to marry and open a store. He thereafter became involved in the Lowry War and in 1871 was made a colonel in charge of a county militia tasked with suppressing a gang of outlaws in the area. He was killed under disputed circumstances in a meeting with some of the outlaws in May 1872.