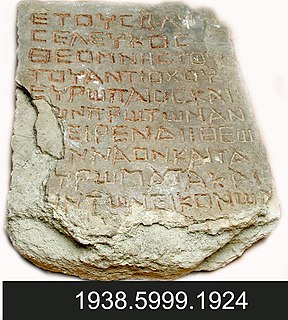

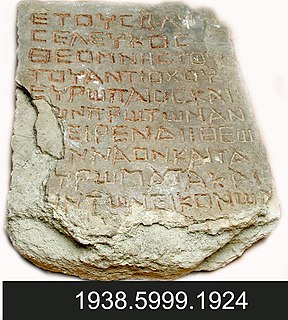

Dura-Europos, also spelled Dura-Europus, was a Hellenistic, Parthian and Roman border city built on an escarpment 90 metres above the southwestern bank of the Euphrates river. It is located near the village of Salhiyé, in today's Syria. In 113 BC, Parthians conquered the city, and held it, with one brief Roman intermission, until 165 AD. Under Parthian rule, it became an important provincial administrative centre. The Romans decisively captured Dura-Europos in 165 AD and greatly enlarged it as their easternmost stronghold in Mesopotamia, until it was captured by the Sasanian Empire after a siege in 256–57 AD. Its population was deported, and after it was abandoned, it was covered by sand and mud and disappeared from sight.

The Dura-Europos synagogue was an ancient synagogue uncovered at Dura-Europos, Syria, in 1932. The synagogue contains a forecourt and house of assembly with painted walls depicting people and animals, and a Torah shrine in the western wall facing Jerusalem. It was built backing on to the city wall, which was important in its survival. The last phase of construction was dated by an Aramaic inscription to 244 AD, making it one of the oldest synagogues in the world. It was unique among the many ancient synagogues that have emerged from archaeological digs as the structure was preserved virtually intact, and it had extensive figurative wall-paintings, which came as a considerable surprise to scholars. These paintings are now displayed in the National Museum of Damascus.

The scutum was a type of shield used among Italic peoples in antiquity, and then by the army of ancient Rome starting about the fourth century BC.

Mikhail Ivanovich Rostovtzeff, or Rostovtsev was a Russian historian whose career straddled the 19th and 20th centuries and who produced important works on ancient Roman and Greek history. He was a member of the Russian Academy of Science.

The Sasanian army was the primary military body of the Sasanian armed forces, serving alongside the Sasanian navy. The birth of the army dates back to the rise of Ardashir I, the founder of the Sasanian Empire, to the throne. Ardashir aimed at the revival of the Persian Empire, and to further this aim, he reformed the military by forming a standing army which was under his personal command and whose officers were separate from satraps, local princes and nobility. He restored the Achaemenid military organizations, retained the Parthian cavalry model, and employed new types of armour and siege warfare techniques. This was the beginning for a military system which served him and his successors for over 400 years, during which the Sasanian Empire was, along with the Roman Empire and later the East Roman Empire, one of the two superpowers of Late Antiquity in Western Eurasia. The Sasanian army protected Eranshahr from the East against the incursions of central Asiatic nomads like the Hephthalites and Turks, while in the west it was engaged in a recurrent struggle against the Roman Empire.

Frank Edward Brown was a preeminent Mediterranean archaeologist.

Simon James is an archeologist of the Iron Age and Roman period and an author. He is Professor of Archaeology at the University of Leicester in England. His research interests are the Roman world and its interactions with the Celts and Middle Eastern peoples.

The Dura-Europos church is the earliest identified Christian house church. It is located in Dura-Europos in Syria. It is one of the earliest known Christian churches, and was apparently a normal domestic house converted for worship some time between 233 and 256, when the town was abandoned after conquest by the Persians. It is less famous, smaller, and more modestly decorated than the nearby Dura-Europos synagogue, though there are many other similarities between them.

Clark Hopkins was an American archaeologist. During the 1930s he led the joint French-American excavations at Dura Europos. In later years he was professor of art and archeology at the University of Michigan.

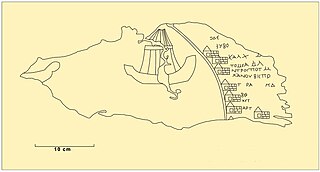

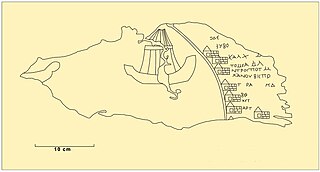

The Dura-Europos route map, also known as stages map, is the fragment of a speciality map from Late Antiquity discovered 1923 in Dura-Europos. The map had been drawn onto the leather covering of a shield by a Roman soldier of the Cohors XX Palmyrenorum between AD 230 and AD 235. The fragment is considered the oldest map of Europe preserved in the original.

The siege of Dura Europos took place when the Sasanians under Shapur I besieged the Roman city of Dura-Europos in 256 after capturing Antioch.

Parthian art was Iranian art made during the Parthian Empire from 247 BC to 224 AD, based in the Near East. It has a mixture of Persian and Hellenistic influences. For some time after the period of the Parthian Empire, art in its styles continued for some time. A typical feature of Parthian art is the frontality of the people shown. Even in narrative representations, the actors do not look at the object of their action, but at the viewer. These are features that anticipate the art of medieval Europe and Byzantium.

The Temple of the Gadde is a double temple in the Syrian city of Dura-Europos, located near the agora. It was dedicated to the protective deities Gaddē of Dura-Europos and the nearby city of Palmyra. It was excavated between 1934 and January 1936 by the French/American expedition of Yale University, led by Michael Rostovtzeff.

The Temple of Zeus Kyrios stood in the city of Dura-Europos (Syria) and was probably built in the first century BC. It was excavated in 1934 by a joint French-American expedition.

The Temple of Zeus Theos at Dura Europos was built in the second century AD and was among the most important sanctuaries of the city. The structure was located in the centre of the settlement. It had an area of around 37 m2 and took up half an insula. It was excavated by an American-French team between December 1933 and March 1939.

The Temple of Adonis in Dura-Europos was discovered by a French-American expedition of Yale University led by Michael Rostovtzeff and was excavated between 1931 and 1934.

The Statue of Hercules was discovered in the Temple of Zeus Megistos in Dura-Europos during the 1935–1937 excavations undertaken by Yale University and the French Academy. The statue dates from the period of Roman rule at Dura-Europos. It is now in the possession of the Yale Art Gallery.

The Palace of the Dux Ripae was the largest and most important building in Dura-Europos during the period of Roman rule. According to the inscriptions, the Palace was erected under Elagabalus and it seems to have survived until the Sassanid conquest of Dura-Europos in AD 256.

Susan M. Hopkins (1900–69) was an archaeologist known for her work on the excavations at Dura-Europos.

The so-called Dolicheneum is a temple in Dura Europos in the east of today's Syria, where Jupiter Dolichenus and god called Zeus Helios Mithras Turmasgade may have been worshiped. The remains of the temple were excavated in 1935/36, but results were never fully published.