The Akita is a Japanese dog breed of large size. Originating from the mountains of northern Japan, the Akita has a short double coat similar to that of many other northern spitz breeds. Historically, they were used by matagi for guarding and the hunting of bears.

Dandruff is a skin condition that mainly affects the scalp. Symptoms include flaking and sometimes mild itchiness. It can result in social or self-esteem problems. A more severe form of the condition, which includes inflammation of the skin, is known as seborrhoeic dermatitis.

A sebaceous gland or oil gland is a microscopic exocrine gland in the skin that opens into a hair follicle to secrete an oily or waxy matter, called sebum, which lubricates the hair and skin of mammals. In humans, sebaceous glands occur in the greatest number on the face and scalp, but also on all parts of the skin except the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. In the eyelids, meibomian glands, also called tarsal glands, are a type of sebaceous gland that secrete a special type of sebum into tears. Surrounding the female nipples, areolar glands are specialized sebaceous glands for lubricating the nipples. Fordyce spots are benign, visible, sebaceous glands found usually on the lips, gums and inner cheeks, and genitals.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis is a long-term skin disorder. Symptoms include flaky, scaly, greasy, and occasionally itchy and inflamed skin. Areas of the skin rich in oil-producing glands are often affected including the scalp, face, and chest. It can result in social or self-esteem problems. In babies, when the scalp is primarily involved, it is called cradle cap. Seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp may be described in lay terms as dandruff due to the dry, flaky character of the skin. However, as dandruff may refer to any dryness or scaling of the scalp, not all dandruff is seborrhoeic dermatitis. Seborrhoeic dermatitis is sometimes inaccurately referred to as seborrhoea.

The Poodle, called the Pudel in German and the Caniche in French, is a breed of water dog. The breed is divided into four varieties based on size, the Standard Poodle, Medium Poodle, Miniature Poodle and Toy Poodle, although the Medium Poodle is not universally recognised. They have a distinctive thick, curly coat that comes in many colors and patterns, with only solid colors recognized by breed registries. Poodles are active and intelligent, and are particularly able to learn from humans. Poodles tend to live 10–18 years, with smaller varieties tending to live longer than larger ones.

Adenitis is a general term for an inflammation of a gland. Often it is used to refer to lymphadenitis which is the inflammation of a lymph node.

Demodicosis, also called Demodex folliculitis in humans and demodectic mange or red mange in animals, is caused by a sensitivity to and overpopulation of Demodexspp. as the host's immune system is unable to keep the mites under control.

The Havanese, a bichon-type dog, is the national dog of Cuba, developed from the now extinct Blanquito de la Habana. The Blanquito descended from the also now-extinct Bichón Tenerife. It is believed that the Blanquito was eventually cross-bred with other bichon types, including the poodle, to create what is now known as the Havanese. They are sometimes referred to as "Havana Silk Dogs", but this is a separate breed, which has been bred to meet the original Cuban standards.

Skin disorders are among the most common health problems in dogs, and have many causes. The condition of a dog's skin and coat is also an important indicator of its general health. Skin disorders of dogs vary from acute, self-limiting problems to chronic or long-lasting problems requiring life-time treatment. Skin disorders may be primary or secondary in nature, making diagnosis complicated.

The coat of the domestic dog refers to the hair that covers its body. Dogs demonstrate a wide range of coat colors, patterns, textures, and lengths.

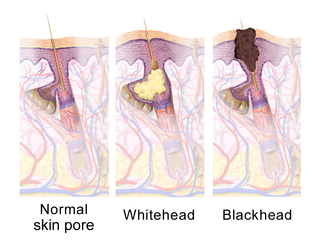

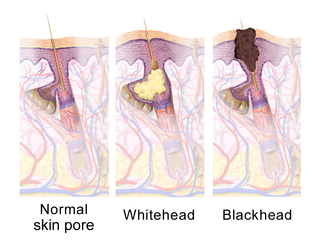

A comedo is a clogged hair follicle (pore) in the skin. Keratin combines with oil to block the follicle. A comedo can be open (blackhead) or closed by skin (whitehead) and occur with or without acne. The word "comedo" comes from the Latin comedere, meaning "to eat up", and was historically used to describe parasitic worms; in modern medical terminology, it is used to suggest the worm-like appearance of the expressed material.

Follicular dysplasia is a genetic disease of dogs causing alopecia, also called hair loss. It is caused by hair follicles that are misfunctioning due to structural abnormality. There are several types, some affecting only certain breeds. Diagnosis is achieved through a biopsy, and treatment is rarely successful. Certain breeds, such as the Mexican Hairless Dog and Chinese Crested Dog, are bred specifically for alopecia.

Dogs, as with all mammals, have natural odors. Natural dog odor can be unpleasant to dog owners, especially when dogs are kept inside the home, as some people are not used to being exposed to the natural odor of a non-human species living in proximity to them. Dogs may also develop unnatural odors as a result of skin disease or other disorders or may become contaminated with odors from other sources in their environment.

Feline acne is a problem seen in cats primarily involving the formation of blackheads accompanied by inflammation on the cat's chin and surrounding areas that can cause lesions, alopecia, and crusty sores. In many cases, symptoms are mild and the disease does not require treatment. Mild cases will resemble dirt on the cat's chin, but the "dirt" will not be brushed off. More severe cases, however, may respond slowly to treatment and seriously detract from the health and appearance of the cat. Feline acne can affect cats of any age, sex, or breed, although Persian cats are also likely to develop acne on the face and in the skin folds. This problem can happen once, reoccur, or even persistent throughout the cat's life.

Pyotraumatic dermatitis, also known as a hot spot or acute moist dermatitis, is a common infection of the skin surface of dogs, particularly those with thick or long coats. It occurs following self-inflicted trauma of the skin. Pyotraumatic dermatitis rarely affects cats.

Dog grooming refers to the hygienic care of a dog, a process by which a dog's physical appearance is enhanced. A dog groomer is a professional that is responsible for maintaining a dog’s hygiene and appearance by offering services such as bathing, brushing, hair trimming, nail clipping and ear cleaning.

Hypoadrenocorticism in dogs, or, as it is known in people, Addison's disease, is an endocrine system disorder that occurs when the adrenal glands fail to produce enough hormones for normal function. The adrenal glands secrete glucocorticoids such as cortisol and mineralocorticoids such as aldosterone; when proper amounts of these are not produced, the metabolic and electrolyte balance is upset. Mineralocorticoids control the amount of potassium, sodium, and water in the body. Hypoadrenocorticism is fatal if left untreated.

Scarring hair loss, also known as cicatricial alopecia, is the loss of hair which is accompanied with scarring. This is in contrast to non scarring hair loss.

Infantile acne is a form of acne that begins in very young children. Typical symptoms include inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions, papules and pustules most commonly present on the face. No cause of infantile acne has been established but it may be caused by increased sebaceous gland secretions due to elevated androgens, genetics and the fetal adrenal gland causing increased sebum production. Infantile acne can resolve by itself by age 1 or 2. However, treatment options include topical benzyl peroxide, topical retinoids and topical antibiotics in most cases.