Related Research Articles

Sagas are prose stories and histories, composed in Iceland and to a lesser extent elsewhere in Scandinavia.

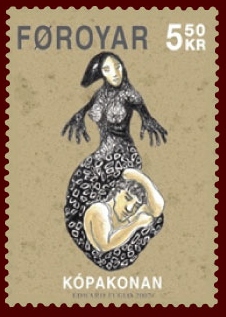

Selkies are mythological creatures that can shapeshift between seal and human forms by removing or putting on their seal skin. They feature prominently in the oral traditions and mythology of various cultures, especially those of Celtic and Norse origin. The term “selkie” derives from the Scots word for “seal”, and is also spelled as silkies, sylkies, or selchies. Selkies are sometimes referred to as selkie folk, meaning 'seal folk'. Selkies are mainly associated with the Northern Isles of Scotland, where they are said to live as seals in the sea but shed their skin to become human on land.

Sturlunga saga is a collection of Icelandic sagas by various authors from the 12th and 13th centuries; it was assembled in about 1300, in Old Norse. It mostly deals with the story of the Sturlungs, a powerful family clan during the eponymous Age of the Sturlungs period of the Icelandic Commonwealth.

Jón Arason was an Icelandic Roman Catholic bishop and poet, who was executed in his struggle against the imposition of the Protestant Reformation in Iceland.

Knýtlinga saga is an Icelandic kings' saga written in the 1250s, which deals with the kings who ruled Denmark from the early 10th century to the time when the book was written.

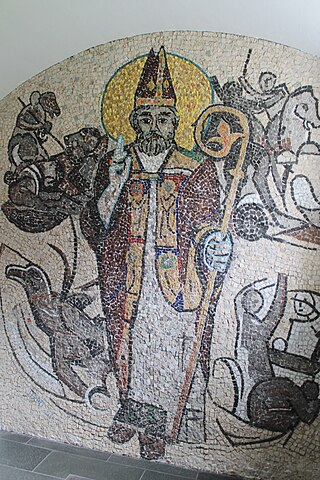

Guðmundur Arason was an influential 12th and 13th century Icelandic saintly bishop who took part in increasing the powers of the Catholic Church in medieval Iceland. His story is recorded in several manuscripts, most notably Prestssaga Guðmundar góða. He is often referred to as Guðmundur góði.

Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar or Hákonar saga gamla is an Old Norse Kings' Saga, telling the story of the life and reign of King Haakon Haakonarson of Norway.

Gunnlaugr Leifsson was an Icelandic scholar, author and poet. He was a Benedictine monk at the Þingeyraklaustur monastery in the north of Iceland. Many sources refer to him simply as Gunnlaugr munkr or Gunnlaugr the Monk.

In Scandinavian folklore, a marmennill is a merman that often features in stories after having being accidentally caught at sea by fishermen. The creature is typically known for its ability to see the future or to reveal otherwise hidden knowledge, often laughing when he sees others acting foolishly.

Svarfdæla saga is one of the sagas of Icelanders. It was first recorded in the first half of the 14th century. It describes disputes which arise during the early settlement of Svarfaðardalur, a valley in central north Iceland.

Ölkofra þáttr, the "Tale of Ölkofri" or the "Tale of Ale-Hood", is a þáttr, a minor Old Norse prose genre related to the sagas of Icelanders. Preserved in the 14th-century manuscript known as Möðruvallabók and other post-Reformation copies, the tale is a satire on the judicial system of the medieval Icelandic Commonwealth. It tells the story of an ale-brewer, named Þórhallr but known as Ölkofri or "Ale-Hood" for the hood that he habitually wears. Ölkofri accidentally sets fire to some valuable woodland belonging to six powerful Icelandic chieftains. These chieftains consequently file suit against him at the Althing in an effort to get him outlawed, but thanks to the efforts of men who unexpectedly come to his aid, Ölkofri manages to escape this fate.

Einarr Gilsson was an Icelandic poet and official. He was the lögmaður of northern and western Iceland from 1367 to 1369. He is mentioned already in letters dating from 1339 and 1340 but his years of birth and death are unknown. He appears to have lived in Skagafjörður.

Arngrímr Brandsson was an Icelandic cleric and writer.

Guðmundar saga biskups or Guðmundar saga Arasonar is an Icelandic bishops' saga, existing in several different versions, recounting the life of Bishop Guðmundur Arason (1161–1237). Since the saga survives in different versions, it is common to speak of it in the plural, as Guðmundar sögur.

Ormr Ásláksson was Bishop of Hólar, Iceland's northern diocese, from 1343-56.

The bishops' saga is a genre of medieval Icelandic sagas, mostly thirteenth- and earlier fourteenth-century prose histories dealing with bishops of Iceland's two medieval dioceses of Skálholt and Hólar.

Maríu saga is an Old Norse-Icelandic biography of the Virgin Mary. Because of the wide range of sources used by its compiler and the way theological commentary has been interspersed with biography, the work is considered "unique within the continental medieval tradition on Mary's life."

Saints' sagas are a genre of Old Norse sagas comprising the prose hagiography of medieval western Scandinavia.

Páls saga biskups is an Old Norse account of the life of Páll Jónsson, bishop of the Icelandic episcopal see Skálholt.

References

- ↑ Marlene Ciklamini, 'Folklore and Hagiography in Arngrímr’s Guðmundar saga Arasonar,' Fabula, 49 (2008), 1–18, doi : 10.1515/fabl.2008.002.

- ↑ The summary is adapted from that of Gunnlaugur Bjarnason, 'Tveir heimar mætast: Guðmundur Arason biskup, hetja og vörður gegn illsku' (unpublished BA dissertation, University of Iceland, 2017), pp. 10-11, citing Biskupa sögur, ed. by Jón Sigurðarson and Guðbrandur Vigfússon, 2 vols (Copenhagen: Møller, 1858–78), II 78-81.

- ↑ Guðmundsdóttir, Soffía Guðný. "Selkolluvísur". Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages.

- ↑ Mart Kuldkepp, 'The People, the Bishop, and the Beast: Remediation and Reconciliation in Einarr Gilsson’s Selkolluvísur,' in Supernatural Encounters in Old Norse Literature and Tradition, ed. by Daviel Sävborg and Karen Bek-Pedersen, Borders, Boundaries, Landscapes, 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), pp. 105-22 doi : 10.1484/M.BBL-EB.5.116082; ISBN 978-2-503-57531-5.

- ↑ Biskupa sögur, ed. by Jón Sigurðarson and Guðbrandur Vigfússon, 2 vols (Copenhagen: Møller, 1858–78), I 604-8.

- ↑ Gunnlaugur Bjarnason, 'Tveir heimar mætast: Guðmundur Arason biskup, hetja og vörður gegn illsku' (unpublished BA dissertation, University of Iceland, 2017), p. 11 (n. 43).

- ↑ Bengt af Klintberg, 'Scandinavian Folklore Parallels to the Narrative about Selkolla in Guðmundar saga biskups,' in Supernatural Encounters in Old Norse Literature and Tradition, ed. by Daviel Sävborg and Karen Bek-Pedersen, Borders, Boundaries, Landscapes, 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), pp. 59-74 doi : 10.1484/M.BBL-EB.5.116080; ISBN 978-2-503-57531-5.

- ↑ Sturlunga saga including the Íslendinga saga of lawman Sturla Thordsson and other works , 2 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1878), I 223.

- ↑ Cf. Sturla Þórðarsson: Íslendinga saga, in Sturlunga saga 1, ed. by Jón Jóhannesson, Magnús Finnbogason and Kristján Eldjárn (Reykjavík 1946), 229–534 (ch. 25, p. 255).

- ↑ Margaret Cormack, 'Saints, Seals, and Demons: The Stories of Selkolla', in Supernatural Encounters in Old Norse Literature and Tradition, ed. by Daviel Sävborg and Karen Bek-Pedersen, Borders, Boundaries, Landscapes, 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), pp. 75-103 doi : 10.1484/M.BBL-EB.5.116081; ISBN 978-2-503-57531-5.

- ↑ K. A. Lund, 'Just Like Magic: Activating Landscape of Witchcraft and Sorcery in Rural Tourism, Iceland', in The Changing World Religion Map: Sacred Places, Identities, Practices and Politics, ed. by Stanley D. Brunn and Donna A. Gilbreath (Dordrecht: Springer, 2014) 767–782 (pp. 777-78), doi : 10.1007/978-94-017-9376-6_38.

- ↑ Sean B. Lawing, 'The Place of the Evil: Infant Abandonment in Old Norse Society', Scandinavian Studies (2013), 133-50 (pp. 146-47).

- ↑ Daniel Sävborg, 'Búi the Dragon: Some Intertexts of Jómsvíkinga Saga, Scripta Islandica: Isländska Sällskapets Årsbok, 65 (2014), 101-17 (pp. 112-13).

- ↑ Bengt af Klintberg, 'Scandinavian Folklore Parallels to the Narrative about Selkolla in Guðmundar saga biskups, in Supernatural Encounters in Old Norse Literature and Tradition, ed. by Daviel Sävborg and Karen Bek-Pedersen, Borders, Boundaries, Landscapes, 1 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), pp. 59-74 doi : 10.1484/M.BBL-EB.5.116080; ISBN 978-2-503-57531-5.