H1 was a particle detector operated at the HERA collider at the German national laboratory DESY in Hamburg. The first studies for the H1 experiment were proposed in 1981. The H1 detector began operating together with HERA in 1992 and took data until 2007. It consisted of several different detector components, measured about 12 m × 15 m × 10 m and weighed 2800 tons. It was one of four detectors along the HERA accelerator.

The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider is the first and one of only two operating heavy-ion colliders, and the only spin-polarized proton collider ever built. Located at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) in Upton, New York, and used by an international team of researchers, it is the only operating particle collider in the US. By using RHIC to collide ions traveling at relativistic speeds, physicists study the primordial form of matter that existed in the universe shortly after the Big Bang. By colliding spin-polarized protons, the spin structure of the proton is explored.

High-energy nuclear physics studies the behavior of nuclear matter in energy regimes typical of high-energy physics. The primary focus of this field is the study of heavy-ion collisions, as compared to lighter atoms in other particle accelerators. At sufficient collision energies, these types of collisions are theorized to produce the quark–gluon plasma. In peripheral nuclear collisions at high energies one expects to obtain information on the electromagnetic production of leptons and mesons that are not accessible in electron–positron colliders due to their much smaller luminosities.

HERA was a particle accelerator at DESY in Hamburg. It was operated from 1992 to 30 June 2007. At HERA, electrons or positrons were brought to collision with protons at a center-of-mass energy of 320 GeV. HERA was used mainly to study the structure of protons and the properties of quarks, laying the foundation for much of the science done at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at the CERN particle physics laboratory today. HERA is the only lepton–proton collider in the world to date and was on the energy frontier in certain regions of the kinematic range.

Two-photon physics, also called gamma–gamma physics, is a branch of particle physics that describes the interactions between two photons. Normally, beams of light pass through each other unperturbed. Inside an optical material, and if the intensity of the beams is high enough, the beams may affect each other through a variety of non-linear effects. In pure vacuum, some weak scattering of light by light exists as well. Also, above some threshold of this center-of-mass energy of the system of the two photons, matter can be created.

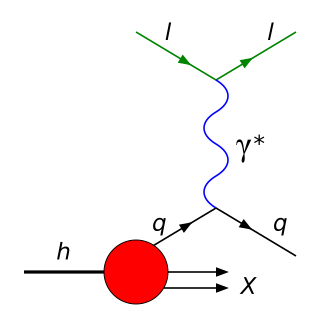

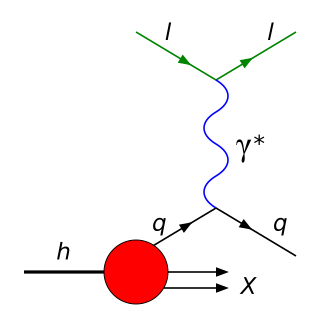

In particle physics, deep inelastic scattering is the name given to a process used to probe the insides of hadrons, using electrons, muons and neutrinos. It was first attempted in the 1960s and 1970s and provided the first convincing evidence of the reality of quarks, which up until that point had been considered by many to be a purely mathematical phenomenon. It is an extension of Rutherford scattering to much higher energies of the scattering particle and thus to much finer resolution of the components of the nuclei.

The Drell–Yan process occurs in high energy hadron–hadron scattering. It takes place when a quark of one hadron and an antiquark of another hadron annihilate, creating a virtual photon or Z boson which then decays into a pair of oppositely-charged leptons. Importantly, the energy of the colliding quark-antiquark pair can be almost entirely transformed into the mass of new particles. This process was first suggested by Sidney Drell and Tung-Mow Yan in 1970 to describe the production of lepton–antilepton pairs in high-energy hadron collisions. Experimentally, this process was first observed by J.H. Christenson et al. in proton–uranium collisions at the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron.

In particle physics, the parton model is a model of hadrons, such as protons and neutrons, proposed by Richard Feynman. It is useful for interpreting the cascades of radiation produced from quantum chromodynamics (QCD) processes and interactions in high-energy particle collisions.

The Mainz Microtron, abbreviated MAMI, is a microtron which provides a continuous wave, high intensity, polarized electron beam with an energy up to 1.6 GeV. MAMI is the core of an experimental facility for particle, nuclear and X-ray radiation physics at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz (Germany). It is one of the largest campus-based accelerator facilities for basic research in Europe. The experiments at MAMI are performed by about 200 physicists of many countries organized in international collaborations.

The NA58 experiment, or COMPASS is a 60-metre-long fixed-target experiment at the M2 beam line of the SPS at CERN. The experimental hall is located at the CERN North Area, close to the French village of Prévessin-Moëns. The experiment is a two-staged spectrometer with numerous tracking detectors, particle identification and calorimetry. The physics results are extracted by recording and analysing the final states of the scattering processes.

Arie Bodek is an American experimental particle physicist and the George E. Pake Professor of Physics at the University of Rochester.

Quantum chromodynamics binding energy, gluon binding energy or chromodynamic binding energy is the energy binding quarks together into hadrons. It is the energy of the field of the strong force, which is mediated by gluons. Motion-energy and interaction-energy contribute most of the hadron's mass.

The EMC effect is the surprising observation that the cross section for deep inelastic scattering from an atomic nucleus is different from that of the same number of free protons and neutrons. From this observation, it can be inferred that the quark momentum distributions in nucleons bound inside nuclei are different from those of free nucleons. This effect was first observed in 1983 at CERN by the European Muon Collaboration, hence the name "EMC effect". It was unexpected, since the average binding energy of protons and neutrons inside nuclei is insignificant when compared to the energy transferred in deep inelastic scattering reactions that probe quark distributions. While over 1000 scientific papers have been written on the topic and numerous hypotheses have been proposed, no definitive explanation for the cause of the effect has been confirmed. Determining the origin of the EMC effect is one of the major unsolved problems in the field of nuclear physics.

James Daniel "BJ" Bjorken is an American theoretical physicist. He was a Putnam Fellow in 1954, received a BS in physics from MIT in 1956, and obtained his PhD from Stanford University in 1959. He was a visiting scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study in the fall of 1962. Bjorken is emeritus professor in the SLAC Theory Group at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, and was a member of the Theory Department of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (1979–1989).

The photon structure function, in quantum field theory, describes the quark content of the photon. While the photon is a massless boson, through certain processes its energy can be converted into the mass of massive fermions. The function is defined by the process e + γ → e + hadrons. It is uniquely characterized by the linear increase in the logarithm of the electronic momentum transfer logQ2 and by the approximately linear rise in x, the fraction of the quark momenta within the photon. These characteristics are borne out by the experimental analyses of the photon structure function.

The idea that matter consists of smaller particles and that there exists a limited number of sorts of primary, smallest particles in nature has existed in natural philosophy at least since the 6th century BC. Such ideas gained physical credibility beginning in the 19th century, but the concept of "elementary particle" underwent some changes in its meaning: notably, modern physics no longer deems elementary particles indestructible. Even elementary particles can decay or collide destructively; they can cease to exist and create (other) particles in result.

An electron–ion collider (EIC) is a type of particle accelerator collider designed to collide spin-polarized beams of electrons and ions, in order to study the properties of nuclear matter in detail via deep inelastic scattering. In 2012, a whitepaper was published, proposing the developing and building of an EIC accelerator, and in 2015, the Department of Energy Nuclear Science Advisory Committee (NSAC) named the construction of an electron–ion collider one of the top priorities for the near future in nuclear physics in the United States.

In high energy particle physics, specifically in hadron-beam scattering experiments, transverse momentum distributions (TMDs) are the distributions of the hadron's quark or gluon momenta that are perpendicular to the momentum transfer between the beam and the hadron. Specifically, they are probability distributions to find inside the hadron a parton with a transverse momentum and longitudinal momentum fraction . TMDs provide information on the confined motion of quarks and gluons inside the hadron and complement the information on the hadron structure provided by parton distribution functions (PDFs) and generalized parton distributions (GPDs). In all, TMDs and PDFs provide the information of the momentum distribution of the quarks, and the GPDs, the information on their spatial distribution.

In quantum field theory, a sum rule is a relation between a static quantity and an integral over a dynamical quantity. Therefore, they have a form such as: