A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input. An individual's construction of reality, not the objective input, may dictate their behavior in the world. Thus, cognitive biases may sometimes lead to perceptual distortion, inaccurate judgment, illogical interpretation, and irrationality.

A heuristic (; from Ancient Greek εὑρίσκω 'method of discovery', or heuristic technique is any approach to problem solving that employs a pragmatic method that is not fully optimized, perfected, or rationalized, but is nevertheless "good enough" as an approximation or attribute substitution. Where finding an optimal solution is impossible or impractical, heuristic methods can be used to speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution. Heuristics can be mental shortcuts that ease the cognitive load of making a decision.

Heuristic reasoning is often based on induction, or on analogy[.] [...] Induction is the process of discovering general laws [...] Induction tries to find regularity and coherence [...] Its most conspicuous instruments are generalization, specialization, analogy. [...] Heuristic discusses human behavior in the face of problems [...that have been] preserved in the wisdom of proverbs.

Daniel Kahneman was an Israeli-American cognitive scientist best-known for his work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making. He is also known for his work in behavioral economics, for which he was awarded the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences together with Vernon L. Smith. Kahneman's published empirical findings challenge the assumption of human rationality prevailing in modern economic theory. Kahneman became known as the "grandfather of behavioral economics."

Amos Nathan Tversky was an Israeli cognitive and mathematical psychologist and a key figure in the discovery of systematic human cognitive bias and handling of risk.

The availability heuristic, also known as availability bias, is a mental shortcut that relies on immediate examples that come to a given person's mind when evaluating a specific topic, concept, method, or decision. This heuristic, operating on the notion that, if something can be recalled, it must be important, or at least more important than alternative solutions not as readily recalled, is inherently biased toward recently acquired information.

Decision theory is a branch of applied probability theory and analytic philosophy concerned with the theory of making decisions based on assigning probabilities to various factors and assigning numerical consequences to the outcome.

The representativeness heuristic is used when making judgments about the probability of an event being representional in character and essence of a known prototypical event. It is one of a group of heuristics proposed by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the early 1970s as "the degree to which [an event] (i) is similar in essential characteristics to its parent population, and (ii) reflects the salient features of the process by which it is generated". The representativeness heuristic works by comparing an event to a prototype or stereotype that we already have in mind. For example, if we see a person who is dressed in eccentric clothes and reading a poetry book, we might be more likely to think that they are a poet than an accountant. This is because the person's appearance and behavior are more representative of the stereotype of a poet than an accountant.

The clustering illusion is the tendency to erroneously consider the inevitable "streaks" or "clusters" arising in small samples from random distributions to be non-random. The illusion is caused by a human tendency to underpredict the amount of variability likely to appear in a small sample of random or pseudorandom data.

Thomas Dashiff Gilovich an American psychologist who is the Irene Blecker Rosenfeld Professor of Psychology at Cornell University. He has conducted research in social psychology, decision making, and behavioral economics, and has written popular books on these subjects. Gilovich has collaborated with Daniel Kahneman, Richard Nisbett, Lee Ross and Amos Tversky. His articles in peer-reviewed journals on subjects such as cognitive biases have been widely cited. In addition, Gilovich has been quoted in the media on subjects ranging from the effect of purchases on happiness to people's most common regrets, to perceptions of people and social groups. Gilovich is a fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.

The overconfidence effect is a well-established bias in which a person's subjective confidence in their judgments is reliably greater than the objective accuracy of those judgments, especially when confidence is relatively high. Overconfidence is one example of a miscalibration of subjective probabilities. Throughout the research literature, overconfidence has been defined in three distinct ways: (1) overestimation of one's actual performance; (2) overplacement of one's performance relative to others; and (3) overprecision in expressing unwarranted certainty in the accuracy of one's beliefs.

In psychology, a heuristic is an easy-to-compute procedure or rule of thumb that people use when forming beliefs, judgments or decisions. The familiarity heuristic was developed based on the discovery of the availability heuristic by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman; it happens when the familiar is favored over novel places, people, or things. The familiarity heuristic can be applied to various situations that individuals experience in day-to-day life. When these situations appear similar to previous situations, especially if the individuals are experiencing a high cognitive load, they may regress to the state of mind in which they have felt or behaved before. This heuristic is useful in most situations and can be applied to many fields of knowledge; however, there are both positives and negatives to this heuristic as well.

In psychology, the human mind is considered to be a cognitive miser due to the tendency of humans to think and solve problems in simpler and less effortful ways rather than in more sophisticated and effortful ways, regardless of intelligence. Just as a miser seeks to avoid spending money, the human mind often seeks to avoid spending cognitive effort. The cognitive miser theory is an umbrella theory of cognition that brings together previous research on heuristics and attributional biases to explain when and why people are cognitive misers.

Counterfactual thinking is a concept in psychology that involves the human tendency to create possible alternatives to life events that have already occurred; something that is contrary to what actually happened. Counterfactual thinking is, as it states: "counter to the facts". These thoughts consist of the "What if?" and the "If only..." that occur when thinking of how things could have turned out differently. Counterfactual thoughts include things that – in the present – could not have happened because they are dependent on events that did not occur in the past.

Attribute substitution is a psychological process thought to underlie a number of cognitive biases and perceptual illusions. It occurs when an individual has to make a judgment that is computationally complex, and instead substitutes a more easily calculated heuristic attribute. This substitution is thought of as taking place in the automatic intuitive judgment system, rather than the more self-aware reflective system. Hence, when someone tries to answer a difficult question, they may actually answer a related but different question, without realizing that a substitution has taken place. This explains why individuals can be unaware of their own biases, and why biases persist even when the subject is made aware of them. It also explains why human judgments often fail to show regression toward the mean.

Heuristics is the process by which humans use mental shortcuts to arrive at decisions. Heuristics are simple strategies that humans, animals, organizations, and even machines use to quickly form judgments, make decisions, and find solutions to complex problems. Often this involves focusing on the most relevant aspects of a problem or situation to formulate a solution. While heuristic processes are used to find the answers and solutions that are most likely to work or be correct, they are not always right or the most accurate. Judgments and decisions based on heuristics are simply good enough to satisfy a pressing need in situations of uncertainty, where information is incomplete. In that sense they can differ from answers given by logic and probability.

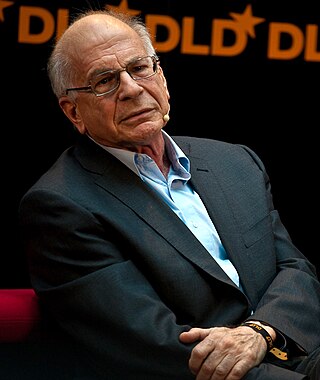

Thinking, Fast and Slow is a 2011 popular science book by psychologist Daniel Kahneman. The book's main thesis is a differentiation between two modes of thought: "System 1" is fast, instinctive and emotional; "System 2" is slower, more deliberative, and more logical.

Illusion of validity is a cognitive bias in which a person overestimates their ability to interpret and predict accurately the outcome when analyzing a set of data, in particular when the data analyzed show a very consistent pattern—that is, when the data "tell" a coherent story.

Social heuristics are simple decision making strategies that guide people's behavior and decisions in the social environment when time, information, or cognitive resources are scarce. Social environments tend to be characterised by complexity and uncertainty, and in order to simplify the decision-making process, people may use heuristics, which are decision making strategies that involve ignoring some information or relying on simple rules of thumb.

Intuitive statistics, or folk statistics, is the cognitive phenomenon where organisms use data to make generalizations and predictions about the world. This can be a small amount of sample data or training instances, which in turn contribute to inductive inferences about either population-level properties, future data, or both. Inferences can involve revising hypotheses, or beliefs, in light of probabilistic data that inform and motivate future predictions. The informal tendency for cognitive animals to intuitively generate statistical inferences, when formalized with certain axioms of probability theory, constitutes statistics as an academic discipline.