Ur was an important Sumerian city-state in ancient Mesopotamia, located at the site of modern Tell el-Muqayyar in Dhi Qar Governorate, southern Iraq. Although Ur was once a coastal city near the mouth of the Euphrates on the Persian Gulf, the coastline has shifted and the city is now well inland, on the south bank of the Euphrates, 16 km (10 mi) from Nasiriyah in modern-day Iraq. The city dates from the Ubaid period c. 3800 BC, and is recorded in written history as a city-state from the 26th century BC, its first recorded king being King Tuttues.

Eridu was a Sumerian city located at Tell Abu Shahrain, also Abu Shahrein or Tell Abu Shahrayn, an archaeological site in southern Mesopotamia. It is located in Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq near the modern city of Basra. Eridu is traditionally believed to be the earliest city in southern Mesopotamia based on the Sumerian King List. Located 12 kilometers southwest of the ancient site of Ur, Eridu was the southernmost of a conglomeration of Sumerian cities that grew around temples, almost in sight of one another. The city gods of Eridu were Enki and his consort Damkina. Enki, later known as Ea, was considered to have founded the city. His temple was called E-Abzu, as Enki was believed to live in Abzu, an aquifer from which all life was believed to stem. According to Sumerian temple hymns another name for the temple of Ea/Enki was called Esira (Esirra).

"... The temple is constructed with gold and lapis lazuli, Its foundation on the nether-sea (apsu) is filled in. By the river of Sippar (Euphrates) it stands. O Apsu pure place of propriety, Esira, may thy king stand within thee. ..."

Larsa, also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon by Berossos and connected with the biblical Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the cult of the sun god Utu with his temple E-babbar. It lies some 25 km (16 mi) southeast of Uruk in Iraq's Dhi Qar Governorate, near the east bank of the Shatt-en-Nil canal at the site of the modern settlement Tell as-Senkereh or Sankarah.

Sippar was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its tell is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, some 69 km (43 mi) north of Babylon and 30 km (19 mi) southwest of Baghdad. The city's ancient name, Sippar, could also refer to its sister city, Sippar-Amnanum ; a more specific designation for the city here referred to as Sippar was Sippar-Yahrurum.

The Kassites were people of the ancient Near East, who controlled Babylonia after the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire c. 1531 BC and until c. 1155 BC.

Shamash, also known as Utu was the ancient Mesopotamian sun god. He was believed to see everything that happened in the world every day, and was therefore responsible for justice and protection of travelers. As a divine judge, he could be associated with the underworld. Additionally, he could serve as the god of divination, typically alongside the weather god Adad. While he was universally regarded as one of the primary gods, he was particularly venerated in Sippar and Larsa. The moon god Nanna (Sin) and his wife Ningal were regarded as his parents, while his twin sister was Inanna (Ishtar). Occasionally other goddesses, such as Manzat and Pinikir, could be regarded as his sisters too. The dawn goddess Aya (Sherida) was his wife, and multiple texts describe their daily reunions taking place on a mountain where the sun was believed to set. Among their children were Kittum, the personification of truth, dream deities such as Mamu, as well as the god Ishum. Utu's name could be used to write the names of many foreign solar deities logographically. The connection between him and the Hurrian solar god Shimige is particularly well attested, and the latter could be associated with Aya as well.

Isin (Sumerian: 𒉌𒋛𒅔𒆠, romanized: I3-si-inki, modern Arabic: Ishan al-Bahriyat) is an archaeological site in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq which was the location of the Ancient Near East city of Isin, occupied from the late 4th millennium Uruk period up until at least the late 1st millennium BC Neo-Babylonian period. It lies about 40 km (25 mi) southeast of the modern city of Al Diwaniyah.

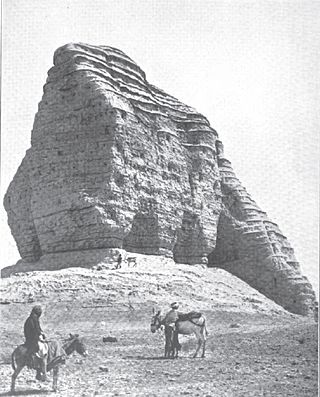

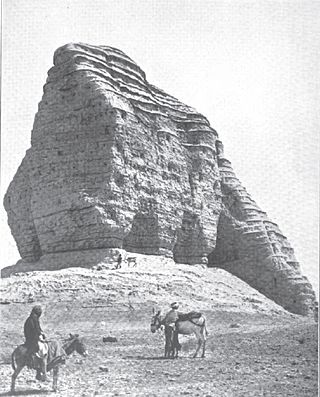

Dur-Kurigalzu was a city in southern Mesopotamia, near the confluence of the Tigris and Diyala rivers, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) west of the center of Baghdad. It was founded by a Kassite king of Babylon, Kurigalzu I and was abandoned after the fall of the Kassite dynasty. The city was of such importance that it appeared on toponym lists in the funerary temple of the Egyptian pharaoh, Amenophis III at Kom el-Hettan". The prefix Dur is an Akkadian term meaning "fortress of", while the Kassite royal name Kurigalzu is believed to have meant "shepherd of the Kassites". The tradition of naming new towns Dur dates back to the Old Babylonian period with an example being Dūr-Ammī-ditāna. The city contained a ziggurat and temples dedicated to Mesopotamian gods, as well as a royal palace which covered 420,000 square meters.

The Kassite dynasty, also known as the third Babylonian dynasty, was a line of kings of Kassite origin who ruled from the city of Babylon in the latter half of the second millennium BC and who belonged to the same family that ran the kingdom of Babylon between 1595 and 1155 BC, following the first Babylonian dynasty. It was the longest known dynasty of that state, which ruled throughout the period known as "Middle Babylonian".

Shullat (Šûllat) and Hanish (Ḫaniš) were a pair of Mesopotamian gods. They were usually treated as inseparable, and appear together in various works of literature. Their character was regarded as warlike and destructive, and they were associated with the weather.

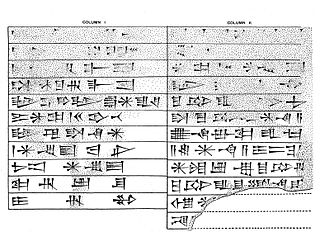

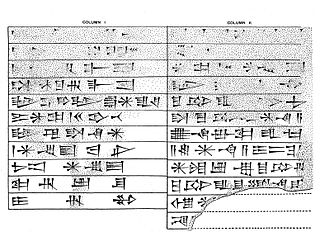

Nazi-Maruttaš, typically inscribed Na-zi-Ma-ru-ut-ta-aš or mNa-zi-Múru-taš, Maruttašprotects him, was a Kassite king of Babylon c. 1307–1282 BC and self-proclaimed šar kiššati, or "King of the World", according to the votive inscription pictured. He was the 23rd of the dynasty, the son and successor of Kurigalzu II, and reigned for twenty six years.

Marad was an ancient Near Eastern city. Marad was situated on the west bank of the then western branch of the Upper Euphrates River west of Nippur in modern-day Iraq and roughly 50 km southeast of Kish, on the Arahtu River. The site was identified in 1912 based on a Neo-Babylonian inscription on a truncated cylinder of Nebuchadrezzar noting the restoration of the temple. The cylinder was not excavated but rather found by locals so its provenance was not certain, as to some extent was the site's identification as Marad. In ancient times it was on the canal, Abgal, running between Babylon and Isin.

Dilbat was an ancient Near Eastern city located 25 kilometers south of Babylon on the eastern bank of the Western Euphrates in modern-day Babil Governorate, Iraq. It lies 15 kilometers southeast of the ancient city of Borsippa. The site of Tell Muhattat, 5 kilometers away, was earlier thought to be Dilbat. The ziggurat E-ibe-Anu, dedicated to Urash, a minor local deity distinct from the earth goddess Urash, was located in the center of the city and was mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Tell al-Lahm is an archaeological site in Dhi Qar Governorate (Iraq). It is 38 km (24 mi) southeast of the site of ancient Ur. Its ancient name is not known with certainty with Kuara, Kisig, and Dur-Iakin having been proposed. The Euphrates River is 256 km (159 mi) away but in antiquity, or a branch of it, ran by the site, continuing to flow until the Muslim Era.

Kurigalzu I, usually inscribed ku-ri-gal-zu but also sometimes with the m or d determinative, the 17th king of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty that ruled over Babylon, was responsible for one of the most extensive and widespread building programs for which evidence has survived in Babylonia. The autobiography of Kurigalzu is one of the inscriptions which record that he was the son of Kadašman-Ḫarbe. Galzu, whose possible native pronunciation was gal-du or gal-šu, was the name by which the Kassites called themselves and Kurigalzu may mean Shepherd of the Kassites.

Adad-apla-iddina, typically inscribed in cuneiform mdIM-DUMU.UŠ-SUM-na, mdIM-A-SUM-na or dIM-ap-lam-i-din-[nam] meaning the storm god “Adad has given me an heir”, was the 8th king of the 2nd Dynasty of Isin and the 4th Dynasty of Babylon and ruled c. 1064–1043. He was a contemporary of the Assyrian King Aššur-bêl-kala and his reign was a golden age for scholarship.

Akkad was the capital of the Akkadian Empire, which was the dominant political force in Mesopotamia during a period of about 150 years in the last third of the 3rd millennium BC.

The Enlil-bānī land grant kudurru is an ancient Mesopotamian narû ša ḫaṣbi, or clay stele, recording the confirmation of a beneficial grant of land by Kassite king Kadašman-Enlil I or Kadašman-Enlil II to one of his officials. It is actually a terra-cotta cone, extant with a duplicate, the orientation of whose inscription, perpendicular to the direction of the cone, in two columns and with the top facing the point, indicates it was to be erected upright,, like other entitlement documents of the period.

Annunitum was a Mesopotamian goddess associated with warfare. She was initially an epithet of Ishtar of Akkad exemplifying her warlike aspect, but by the late third millennium BCE she came to function as a distinct deity. She was the tutelary goddess of the cities of Akkad and Sippar-Amnanum, though she was also worshiped elsewhere in Mesopotamia.

Tell Muhammad, is an ancient Near East archaeological site currently in the outskirts of Baghdad, along the Tigris river in the Diyala region. It is a very short distance from the site of Tell Harmal to the north and not far from the site of Tell al-Dhiba'i to the northeast. The ancient name of the site is unknown though Diniktum has been suggested. The lost city of Akkad has also been proposed. Based on a year name found on one of the cuneiform tablets the name Banaia has also been proposed.