Archosauria is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term, which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and extinct relatives of crocodilians. Modern paleontologists define Archosauria as a crown group that includes the most recent common ancestor of living birds and crocodilians, and all of its descendants. The base of Archosauria splits into two clades: Pseudosuchia, which includes crocodilians and their extinct relatives, and Avemetatarsalia, which includes birds and their extinct relatives.

Argentinosaurus is a genus of giant sauropod dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period in what is now Argentina. Although it is only known from fragmentary remains, Argentinosaurus is one of the largest known land animals of all time, perhaps the largest, measuring 30–35 metres (98–115 ft) long and weighing 65–80 tonnes. It was a member of Titanosauria, the dominant group of sauropods during the Cretaceous. It is widely regarded by many paleontologists as the biggest dinosaur ever, and perhaps lengthwise the longest animal ever, though both claims have no concrete evidence yet.

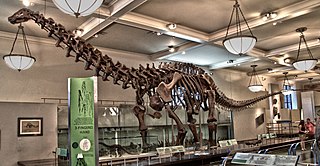

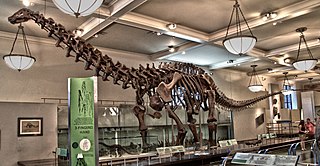

Sauropoda, whose members are known as sauropods, is a clade of saurischian ('lizard-hipped') dinosaurs. Sauropods had very long necks, long tails, small heads, and four thick, pillar-like legs. They are notable for the enormous sizes attained by some species, and the group includes the largest animals to have ever lived on land. Well-known genera include Brachiosaurus, Diplodocus, Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus.

Massospondylus is a genus of sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic. It was described by Sir Richard Owen in 1854 from remains discovered in South Africa, and is thus one of the first dinosaurs to have been named. Fossils have since been found at other locations in South Africa, Lesotho, and Zimbabwe. Material from Arizona's Kayenta Formation, India, and Argentina has been assigned to the genus at various times, but the Arizonan and Argentinian material are now assigned to other genera.

Opisthocoelicaudia is a genus of sauropod dinosaur of the Late Cretaceous Period discovered in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. The type species is Opisthocoelicaudia skarzynskii. A well-preserved skeleton lacking only the head and neck was unearthed in 1965 by Polish and Mongolian scientists, making Opisthocoelicaudia one of the best known sauropods from the Late Cretaceous. Tooth marks on this skeleton indicate that large carnivorous dinosaurs had fed on the carcass and possibly had carried away the now-missing parts. To date, only two additional, much less complete specimens are known, including part of a shoulder and a fragmentary tail. A relatively small sauropod, Opisthocoelicaudia measured about 11.4–13 m (37–43 ft) in length. Like other sauropods, it would have been characterised by a small head sitting on a very long neck and a barrel shaped trunk carried by four column-like legs. The name Opisthocoelicaudia means "posterior cavity tail", alluding to the unusual, opisthocoel condition of the anterior tail vertebrae that were concave on their posterior sides. This and other skeletal features lead researchers to propose that Opisthocoelicaudia was able to rear on its hindlegs.

Brontosaurus is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur that lived in present-day United States during the Late Jurassic period. It was described by American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1879, the type species being dubbed B. excelsus, based on a partial skeleton lacking a skull found in Como Bluff, Wyoming. In subsequent years, two more species of Brontosaurus were named: B. parvus in 1902 and B. yahnahpin in 1994. Brontosaurus lived about 156 to 146 million years ago (mya) during the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian ages in the Morrison Formation of what is now Utah and Wyoming. For decades, the animal was thought to have been a taxonomic synonym of its close relative Apatosaurus, but a 2015 study by Emmanuel Tschopp and colleagues found it to be distinct. It has seen widespread representation in popular culture, being the archetypal "long-necked" dinosaur in general media.

Air sacs are spaces within an organism where there is the constant presence of air. Among modern animals, birds possess the most air sacs (9–11), with their extinct dinosaurian relatives showing a great increase in the pneumatization in their bones. Birds use air sacs for respiration as well as a number of other things. Theropods, like Aerosteon, have many air sacs in the body that are not just in bones, and they can be identified as the more primitive form of modern bird airways. Sauropods are well known for the large number of air pockets in their bones, although one theropod, Deinocheirus, shows a rivalling number of air pockets.

Majungasaurus is a genus of abelisaurid theropod dinosaur that lived in Madagascar from 70 to 66 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous Period, making it one of the last known non-avian dinosaurs that went extinct during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. The genus contains a single species, Majungasaurus crenatissimus. This dinosaur is also called Majungatholus, a name which is considered a junior synonym of Majungasaurus.

The physiology of dinosaurs has historically been a controversial subject, particularly their thermoregulation. Recently, many new lines of evidence have been brought to bear on dinosaur physiology generally, including not only metabolic systems and thermoregulation, but on respiratory and cardiovascular systems as well.

Apatosaurinae is a subfamily of diplodocid sauropods, an extinct group of large, quadrupedal dinosaurs. Apatosaurinae is classified within the family Diplodocidae, which bears the other subfamily Diplodocinae. Apatosaurines are distinguished by their more robust, stocky builds and shorter necks proportionally to the rest of their bodies. Several fairly complete specimens are known, giving a comprehensive view of apatosaurine anatomy.

Aerosteon is a genus of megaraptoran dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of Argentina. Its remains were discovered in 1996 in the Anacleto Formation, which is from the late Campanian. The type and only known species is A. riocoloradensis. Its specific name indicates that its remains were found 1 km north of the Río Colorado, in Mendoza Province, Argentina.

Brachiosaurus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived in North America during the Late Jurassic, about 154 to 150 million years ago. It was first described by American paleontologist Elmer S. Riggs in 1903 from fossils found in the Colorado River valley in western Colorado, United States. Riggs named the dinosaur Brachiosaurus altithorax; the generic name is Greek for "arm lizard", in reference to its proportionately long arms, and the specific name means "deep chest". Brachiosaurus is estimated to have been between 18 and 22 meters long; body mass estimates of the subadult holotype specimen range from 28.3 to 46.9 metric tons. It had a disproportionately long neck, small skull, and large overall size, all of which are typical for sauropods. Atypically, Brachiosaurus had longer forelimbs than hindlimbs, which resulted in a steeply inclined trunk, and a proportionally shorter tail.

Nigersaurus is a genus of rebbachisaurid sauropod dinosaur that lived during the middle Cretaceous period, about 115 to 105 million years ago. It was discovered in the Elrhaz Formation in an area called Gadoufaoua, in Niger. Fossils of this dinosaur were first described in 1976, but it was only named Nigersaurus taqueti in 1999, after further and more complete remains were found and described. The genus name means "Niger reptile", and the specific name honours the palaeontologist Philippe Taquet, who discovered the first remains.

Epipophyses are bony projections of the cervical vertebrae found in archosauromorphs, particularly dinosaurs. These paired processes sit above the postzygapophyses on the rear of the vertebral neural arch. Their morphology is variable and ranges from small, simple, hill-like elevations to large, complex, winglike projections. Epipophyses provided large attachment areas for several neck muscles; large epipophyses are therefore indicative of a strong neck musculature.

The year 2012 in Archosaur paleontology was eventful. Archosaurs include the only living dinosaur group — birds — and the reptile crocodilians, plus all extinct dinosaurs, extinct crocodilian relatives, and pterosaurs. Archosaur palaeontology is the scientific study of those animals, especially as they existed before the Holocene Epoch began about 11,700 years ago. The year 2012 in paleontology included various significant developments regarding archosaurs.

This glossary explains technical terms commonly employed in the description of dinosaur body fossils. Besides dinosaur-specific terms, it covers terms with wider usage, when these are of central importance in the study of dinosaurs or when their discussion in the context of dinosaurs is beneficial. The glossary does not cover ichnological and bone histological terms, nor does it cover measurements.

The year 2017 in archosaur paleontology was eventful. Archosaurs include the only living dinosaur group — birds — and the reptile crocodilians, plus all extinct dinosaurs, extinct crocodilian relatives, and pterosaurs. Archosaur palaeontology is the scientific study of those animals, especially as they existed before the Holocene Epoch began about 11,700 years ago. The year 2017 in paleontology included various significant developments regarding archosaurs.

This article records new taxa of fossil archosaurs of every kind that are scheduled described during the year 2021, as well as other significant discoveries and events related to paleontology of archosaurs that are scheduled to occur in the year 2021.

This article records new taxa of fossil archosaurs of every kind that are scheduled described during the year 2022, as well as other significant discoveries and events related to paleontology of archosaurs that are scheduled to occur in the year 2022.

Ibirania is a genus of dwarf saltasaurine titanosaur dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous São José do Rio Preto Formation of south-east Brazil. The type species is Ibirania parva. It is one of the smallest sauropods known to date, comparable in size to the titanosaur Magyarosaurus.