Chamunda, also known as Chamundeshwari, Chamundi or Charchika, is a fearsome form of Chandi, the Hindu Divine Mother Shakthi and is one of the seven Matrikas.

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez, known as Diego Rivera, was a prominent Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the mural movement in Mexican and international art.

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country's popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society. Her paintings often had strong autobiographical elements and mixed realism with fantasy. In addition to belonging to the post-revolutionary Mexicayotl movement, which sought to define a Mexican identity, Kahlo has been described as a surrealist or magical realist. She is known for painting about her experience of chronic pain.

Oaxaca de Juárez, also Oaxaca City or simply Oaxaca, is the capital and largest city of the eponymous Mexican state Oaxaca. It is the municipal seat for the surrounding Municipality of Oaxaca. It is in the Centro District in the Central Valleys region of the state, in the foothills of the Sierra Madre at the base of the Cerro del Fortín, extending to the banks of the Atoyac River. Heritage tourism makes up an important part of the city's economy, and it has numerous colonial-era structures as well as significant archeological sites and elements of the continuing native Zapotec and Mixtec cultures. The city, together with the nearby archeological site of Monte Albán, was designated in 1987 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is the site of the month-long cultural festival called the "Guelaguetza", which features Oaxacan dance from the seven regions, music, and a beauty pageant for indigenous women.

José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar was a Mexican political lithographer who used relief printing to produce popular illustrations. His work has influenced numerous Latin American artists and cartoonists because of its satirical acuteness and social engagement. He used skulls, calaveras, and bones to convey political and cultural critiques. Among his most enduring works is La Calavera Catrina.

Alebrijes are brightly colored Mexican folk art sculptures of fantastical (fantasy/mythical) creatures.

Louis Henri Jean Charlot was a French-born American painter and illustrator, active mainly in Mexico and the United States.

La Calavera Catrina ("Dapper Skull") or CatrinaLa Calavera Garbancera is a 1910–1913 zinc etching by the Mexican printmaker, cartoon illustrator and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada. Originally a satirization of an upper class woman of the Porfiriato, the character of La Catrina has become an icon of the Mexican Day of the Dead.

![<span class="mw-page-title-main">Calavera</span> Mexican skull model made out of sugar or clay for [[Dia de los Muertos]] celebrations](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/Calavera.jpg/283px-Calavera.jpg)

A calavera is a representation of a human skull. The term is most often applied to edible or decorative skulls made from either sugar or clay, used in the Mexican celebration of the Day of the Dead and the Roman Catholic holiday All Souls' Day. Calavera can also refer to any artistic representations of skulls, such as the lithographs of José Guadalupe Posada. The most widely known calaveras are created with cane sugar and are decorated with items such as colored foil, icing, beads, and feathers. They range in multiple colors.

Rodolfo Nieto Labastida was a Mexican painter of the Oaxacan School.

Mexican Muralism refers to an art project funded by the Mexican government in an attempt to reunify the country under the government post-Mexican Revolution. The project was to allow artists to promote political ideas regarding the social revolution that had just recently ended so that viewers may reflect on how pivotal the revolution was in Mexican history. This was accomplished by way of painting murals, large artworks painted onto the wall itself, containing general social and political messages. Beginning in the 1920s, the muralist project was headed by a group of artists known as "The Big Three" or "The Three Greats". This group was composed of Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. From the 1920s to the 1970s, many murals with nationalistic, social and political messages were created in many public settings such as chapels, schools, government buildings, and much more. The popularity of the Mexican muralist project started a tradition which continues to this day in Mexico; a tradition that has had a significant impact in other parts of the Americas, including the United States, where it served as inspiration for the Chicano art movement.

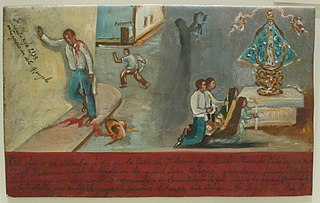

Votive paintings in Mexico go by several names in Spanish such as “ex voto,” “retablo” or “lámina,” which refer to their purpose, place often found, or material from which they are traditionally made respectively. The painting of religious images to give thanks for a miracle or favour received in this country is part of a long tradition of such in the world. The offering of such items has more immediate precedence in both the Mesoamerican and European lines of Mexican culture, but the form that most votive paintings take from the colonial period to the present was brought to Mexico by the Spanish. As in Europe, votive paintings began as static images of saints or other religious figures which were then donated to a church. Later, narrative images, telling the personal story of a miracle or favor received appeared. These paintings were first produced by the wealthy and often on canvas; however, as sheets of tin became affordable, lower classes began to have these painted on this medium. The narrative version on metal sheets is now the traditional and representative form of votive paintings, although modern works can be executed on paper or any other medium.

Cartonería or papier-mâché sculptures are a traditional handcraft in Mexico. The papier-mâché works are also called "carton piedra" for the rigidness of the final product. These sculptures today are generally made for certain yearly celebrations, especially for the Burning of Judas during Holy Week and various decorative items for Day of the Dead. However, they also include piñatas, mojigangas, masks, dolls and more made for various other occasions. There is also a significant market for collectors as well. Papier-mâché was introduced into Mexico during the colonial period, originally to make items for church. Since then, the craft has developed, especially in central Mexico. In the 20th century, the creation of works by Mexico City artisans Pedro Linares and Carmen Caballo Sevilla were recognized as works of art with patrons such as Diego Rivera. The craft has become less popular with more recent generations, but various government and cultural institutions work to preserve it.

Carlomagno Pedro Martínez is a Mexican artist and artisan in “barro negro” ceramics from San Bartolo Coyotepec, in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. He comes from a family of potters in a town noted for the craft. He began molding figures as a child and received artistic training when he was 18. His work has been exhibited in Mexico, the U.S. and Europe and he has been recognized as an artist as well as an artisan. Today, he is also the director of the Museo Estatal de Arte Popular de Oaxaca (MEAPO) in his hometown. In 2014, Martínez was awarded Mexico's National Prize for Arts and Sciences

Ángel Bracho was a Mexican engraver and painter who is best known for his politically themed work associated with the Taller de Gráfica Popular; however he painted a number of notable murals as well. Bracho was from a lower-class family and worked a number of menial jobs before taking night classes for workers at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas. Even though he had only four years of primary school, he then studied as a full-time student at the university. His art career began working with Diego Rivera on the painting of the Abelardo L. Rodríguez market in Mexico City. He was a founding member of the Taller de Gráfica Popular, making posters that would become characteristic of the group. His graphic design work is simple, clean and fine dealing with themes related to social struggles with farm workers, laborers and Mexican landscapes.

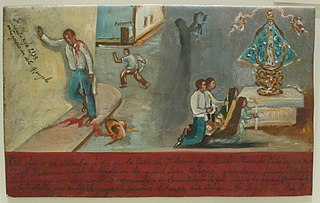

Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central or Dream of a Sunday Afternoon at Alameda Central Park is a 15.6 meter wide mural created by Diego Rivera. It was painted between the years 1946 and 1947, and is the principal work of the Museo Mural Diego Rivera adjacent to the Alameda in the historic center of Mexico City.

The Aguilar family of Ocotlán de Morelos are from a rural town in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico. This town produced only utilitarian items until Isaura Alcantara Diaz began creating decorative figures with her husband Jesus Aguila Revilla. The couple taught their five daughters who continued innovating their own styles and then teaching the two generations after them. Two of the sisters, Guilliermina and Irene have been named “grand masters” by the Fomento Cultural Banamex, for their figures and sets of figures related to the life and traditions of Oaxaca, as well as Mexican icons such as Frida Kahlo and the Virgin of Guadalupe. The younger generations have made their own adaptations with some attaining their own recognition such as Lorenzo Demetrio García Aguilar and Jose Francisco Garcia Vazquez.

Nancy Glenn-Nieto is an American-Mexican actress, model, and fine art painter. She is perhaps best known as a model and an actress in Mexico City; however, her art work has become highly collectable. She is the widow of Mexican Oaxacan painter Rodolfo Nieto.

The Wounded Table is an oil painting by Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. Although lost in 1955, three photos of this painting were taken between 1940 and 1944. The painting was first displayed in January 1940 at the International Surrealism Exhibit at Inés Amor's Gallery of Mexican Art in Mexico City, and a replica is currently displayed in the Kunstmuseum Gehrke-Remund, Baden-Baden, Germany. The painting was last exhibited in Warsaw in 1955, after which it disappeared, and is the subject of an ongoing international search.

Valerie Campos is a Mexican artist. She spent her early years in Los Angeles (California) with street art and lowbrow as some of her first visual influences. Self-taught, she began painting at the age of 22 and moved to Oaxaca (Mexico), internationally known as the city of the Mexican painters.

![<span class="mw-page-title-main">Calavera</span> Mexican skull model made out of sugar or clay for [[Dia de los Muertos]] celebrations](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/Calavera.jpg/283px-Calavera.jpg)