Related Research Articles

Opium is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy Papaver somniferum. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which is processed chemically to produce heroin and other synthetic opioids for medicinal use and for the illegal drug trade. The latex also contains the closely related opiates codeine and thebaine, and non-analgesic alkaloids such as papaverine and noscapine. The traditional, labor-intensive method of obtaining the latex is to scratch ("score") the immature seed pods (fruits) by hand; the latex leaks out and dries to a sticky yellowish residue that is later scraped off and dehydrated. The word meconium historically referred to related, weaker preparations made from other parts of the opium poppy or different species of poppies.

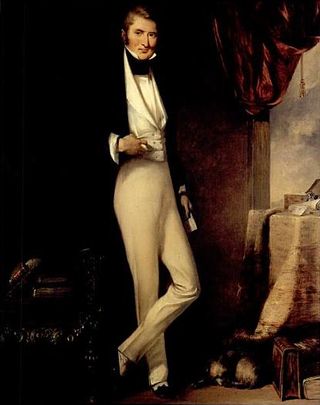

William Jardine was a Scottish physician, opium merchant and trader who co-founded the Hong Kong based conglomerate Jardine, Matheson & Co. Educated in medicine at the University of Edinburgh, in 1802 Jardine obtained a diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. The next year, he became a surgeon's mate aboard the Brunswick belonging to the East India Company, and set sail for India. In May 1817, he abandoned medicine for trade.

The prohibition of drugs through sumptuary legislation or religious law is a common means of attempting to prevent the recreational use of certain intoxicating substances.

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 8th Earl of Shaftesbury Bt DL, styled Lord Ashley between 1851 and 1885, was a British peer. He was the son of The 7th Earl of Shaftesbury.

Sir James Nicolas Sutherland Matheson, 1st Baronet, FRS, was a Scottish opium trader and taipan. Born in Shiness, Lairg, Sutherland, Scotland, he was the son of Captain Donald Matheson. He attended Edinburgh's Royal High School and the University of Edinburgh. He and William Jardine went on to co-found the Hong Kong-based trading conglomerate Jardine Matheson & Co. that became today's Jardine Matheson Holdings.

The Peace Society, International Peace Society or London Peace Society, originally known as the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, was a pioneering British pacifist organisation that was active from 1816 until the 1930s.

Sir Joseph Whitwell Pease, 1st Baronet was a British Liberal Party politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1865 to 1903.

Benjamin Broomhall was a British advocate of foreign missions, administrator of the China Inland Mission (CIM), and author. Broomhall served as the General Secretary of the China Inland Mission,. A boyhood friend of James Hudson Taylor, he became husband to Hudson Taylor’s sister Amelia. As General Secretary of the CIM, he was involved in fund-raising and recruiting missionaries to send to China and acted as editor of the mission magazine, "China's Millions".

In the early 19th century, Western colonial expansion occurred at the same time as an evangelical revival – the Second Great Awakening – throughout the English-speaking world, leading to more overseas missionary activity. The nineteenth century became known as the Great Century of modern religious missions.

Griffith John was a Welsh Christian missionary and translator in China. A member of the Congregational church, he was a pioneer evangelist with the London Missionary Society (LMS), a writer and a translator of the Holy Bible into the Chinese language.

William Garrett Lewis (1821–1885) was a Baptist preacher and pastor of Westbourne Grove Church in Bayswater, London for 33 years. He was an apologist author of two books, Westbourne Grove Sermons and The Trades and Industrial Occupations of the Bible, published by the Religious Tract Society.

Medical missions in China by Catholic and Protestant physicians and surgeons of the 19th and early 20th centuries laid many foundations for modern medicine in China. Western medical missionaries established the first modern clinics and hospitals, provided the first training for nurses, and opened the first medical schools in China. Work was also done in opposition to the abuse of opium. Medical treatment and care came to many Chinese who were addicted, and eventually public and official opinion was influenced in favor of bringing an end to the destructive trade. By 1901, China was the most popular destination for medical missionaries. The 150 foreign physicians operated 128 hospitals and 245 dispensaries, treating 1.7 million patients. In 1894, male medical missionaries comprised 14 percent of all missionaries; women doctors were four percent. Modern medical education in China started in the early 20th century at hospitals run by international missionaries.

Hampden Coit DuBose was a Presbyterian missionary in China with the American Presbyterian Mission (South) and founder of the Anti-Opium League in China. Rev. Dr. Hampden Coit DuBose was the son of Rev. Julius Jesse DuBose and Margaret Eliza Thompson, married Pauline McAlpine, daughter of Augustine Irving McAlpine and Martha Clisby and had seven children with her.

Sylph was a clipper ship built at Sulkea, opposite Calcutta, in 1831 for the Parsi merchant Rustomjee Cowasjee. After her purchase by the Hong Kong-based merchant house Jardine Matheson, in 1833 Sylph set a speed record by sailing from Calcutta to Macao in 17 days, 17 hours. Her primary role was to transport opium between various ports in the Far East. She disappeared en route to Singapore in 1849.

The Royal Commission on Opium was a British Royal Commission that investigated the opium trade in British India in 1893–1895, particularly focusing on the medical impacts of opium consumption within India. Set up by Prime Minister William Gladstone’s government in response to political pressure from the anti-opium movement to ban non-medical sales of opium in India, it ultimately defended the existing system in which opium sales to the public were legal but regulated.

Rev. Frederick Storrs Turner was a British clergyman and campaigner against the opium trade.

Jardine Matheson Holdings Limited is a Hong Kong-based, Bermuda-domiciled British multinational conglomerate. It has a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange and secondary listings on the Singapore Exchange and Bermuda Stock Exchange. The majority of its business interests are in Asia, and its subsidiaries include Jardine Pacific, Jardine Motors, Hongkong Land, Jardine Strategic Holdings, DFI Retail Group, Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group, Jardine Cycle & Carriage and Astra International. It set up the Jardine Scholarship in 1982 and Mindset, a mental health-focused charity, in 2002.

David Sassoon & Co., Ltd. was a trading company operating in the 19th century and early 20th century predominantly in India, China and Japan.

Joseph Pease (1772–1846) was an English Quaker activist. Among a number of reforming interests, he became best known in the context of the British India Society.

The history of opium in China began with the use of opium for medicinal purposes during the 7th century. In the 17th century the practice of mixing opium with tobacco for smoking spread from Southeast Asia, creating a far greater demand.

References

- ↑ Bill Schwarz (6 March 1996). The Expansion of England: Race, Ethnicity and Cultural History. Routledge. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-415-06025-7 . Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- ↑ Hunt Janin (1 October 1999). The India-China Opium Trade in the Nineteenth Century. McFarland. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-7864-0715-6 . Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 A.W. Bob Coats (15 May 1995). The Economic Review. Taylor and Francis. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-415-13135-3 . Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- 1 2 R. G. Tiedemann (1 December 2009). Handbook of Christianity in China: 1800 to the Present. BRILL. p. 358. ISBN 978-90-04-11430-2 . Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kathleen L. Lodwick (1996). Crusaders Against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China, 1874–1917. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 55–66. ISBN 978-0-8131-1924-3 . Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy (2009). Opium: Uncovering the Politics of the Poppy. Harvard University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-674-05134-8 . Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ J.G. Alexander's writings are listed in the catalogue of the Religious Society of Friends, London

- ↑ Jan-Willem Gerritsen (2000). The Control of Fuddle and Flash: A Sociological History of the Regulation of Alcohol and Opiates. BRILL. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-04-11640-5 . Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Harold Traver; Mark S. Gaylord (1992). Drugs, Law, and the State. Transaction Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-56000-082-2 . Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Alan Baumler (2007). The Chinese and Opium under the Republic: Worse Than Floods and Wild Beasts. State University of New York. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7914-6953-8 . Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ↑ Ryan Dunch (January 1, 1997). "Crusaders Against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China, 1874–1917 (Book Review)". International Bulletin of Missionary Research. Overseas Ministries Study Center. Retrieved 24 October 2023– via TheFreeLibrary.

- ↑ The imperial drug trade.(1906 edition), available online

- ↑ Benjamin Broomhall The Truth About Opium Smoking available online.

- ↑ Katherine Mullin, ‘Dyer, Alfred Stace (1849–1926)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Oct 2008 accessed 7 Aug 2012